Rivers, creeks and streams are some of the most valued and recognised natural features in the region, collectively referred to as rivers in this section. The region’s rivers are renowned for recreational activities, are economically valuable for tourism, provide water supply for stock and domestic use, and are an important part of the region’s history, beauty and character. Many of the region’s towns, campgrounds and caravan parks nestle alongside a river or creek.

Across the region, rivers are culturally significant places for Traditional Owners. Besides providing a steady source of food and other resources for daily living, they also serve as boundaries, have ceremonial importance and were historically used as trading routes. Rivers continue to support cultural practices and culturally significant species.

Glenelg River

Hopkins River

Photo: The Standard

Our rivers

Rivers connect inland areas to the coast and allow for the movement of water along with flora and fauna, nutrients and other resources. Their floodplains are an integral part of their function, health and value. Rivers, and other aquatic ecosystems in the region, support a wide diversity of aquatic animals, including:

- 61 species of fish.

- 2 aquatic mammals (platypus and rakali).

- 17 species of freshwater yabbies, crabs, crayfish and shrimp.

- 15 species of frogs, froglets and toads.

- 4 freshwater mussel species.

- 3 turtle species.

The region’s rivers provide habitat for significant native small-bodied fishes. Three nationally listed threatened fish species are found in the region’s rivers – Yarra pygmy perch (Nannoperca obscura), variegated pygmy perch (Nannoperca variegata), Australian grayling (Prototroctes maraena) – and one invertebrate, the Glenelg spiny crayfish (Euastacus bispinosus). Other significant fauna species include invertebrates like the ancient greenling (Hemiphlebia mirabilis).

The riparian zones are critical habitat in heavily cleared landscapes, providing connections between terrestrial and aquatic systems and supporting important flora species like the threatened Gorae leek orchid (Prasophyllum diversflorum) and Wimmera bottle brush (Callistemon wimmerensis). Native vegetation in the riparian zone provides an important buffer, filtering out sediment and other pollutants in the catchment.

Rivers have traditionally been a focus for the development of settlements. During periods of prolonged or heavy rainfall, storm surges or high tides, rising water levels along rivers cause inundation of the surrounding floodplains. While flooding can be a serious problem for the community, it is a natural process and is essential for river health.

People depend on rivers for their way of life and their livelihoods. From fishing to agriculture, the way waterways are managed has a direct impact on people’s lives. Freshwater habitats account for some of the richest biodiversity in the world, and rivers and their floodplains are a vital, vibrant ecosystem for many species.

A key future challenge will be to ensure the protection of life and property, while allowing rivers to maintain their natural flooding processes. Local flood management plans and studies help manage floodplains and outlying areas in the Glenelg Hopkins region that are at high risk of inundation. These towns include Casterton, Hamilton, Warrnambool, Skipton, Ararat, Port Fairy and Heywood. More information about floodplain management can be found in the Glenelg Hopkins Regional Floodplain Management Strategy (2017).

Glenelg spiny crayfish

Wimmera bottlebrush

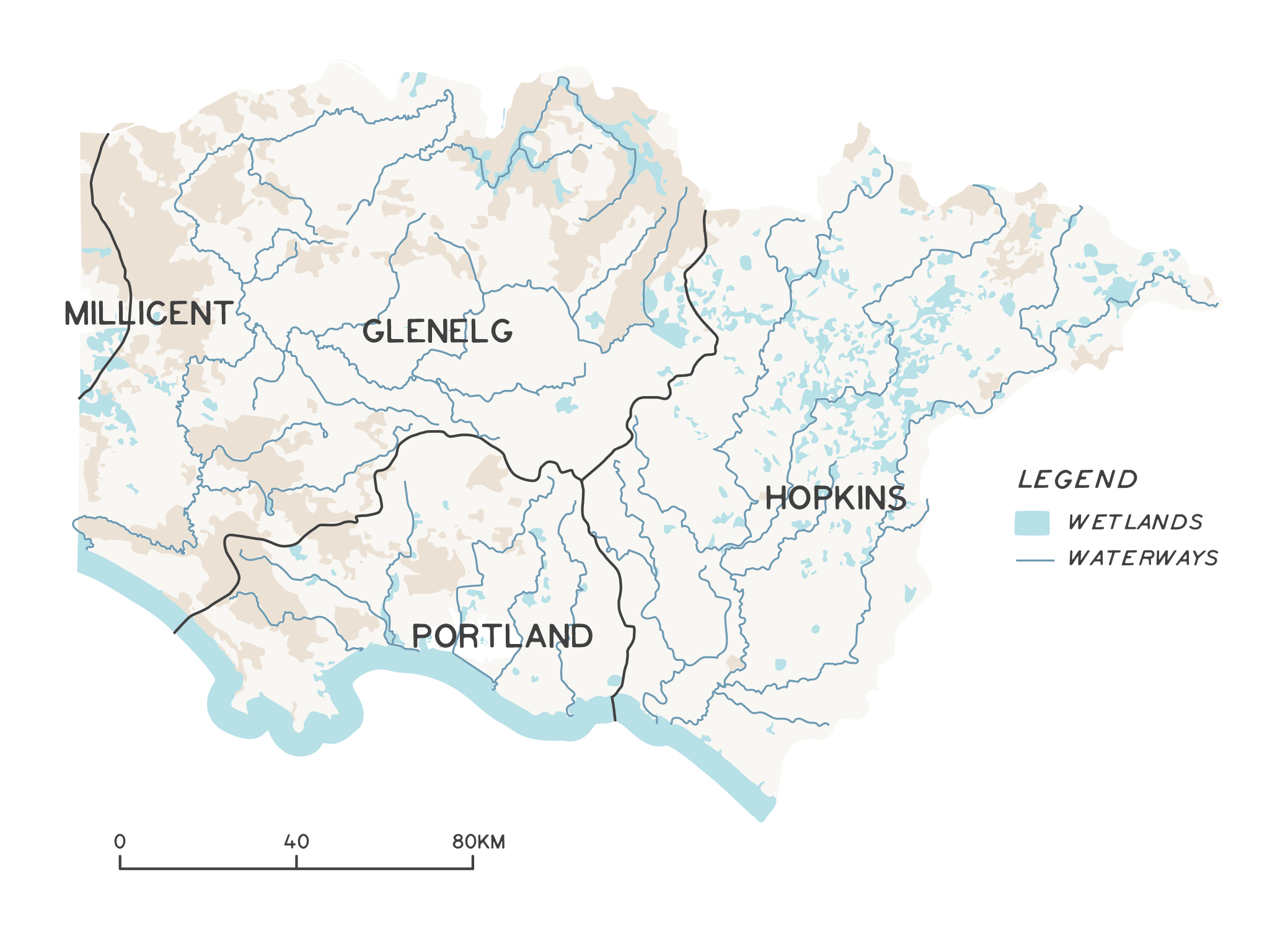

River basins

Glenelg Basin

The Glenelg River is the dominant feature of the Glenelg Basin and longest river in the region, with a 12,738 km2 catchment. The river rises in Gariwerd (Grampians National Park) and flows to the sea through the Lower Glenelg National Park. Between Dartmoor and the coast the river is classified as a heritage river (Heritage Rivers Act 1992). The Glenelg River estuary is internationally recognised as a Ramsar site (the Glenelg Estuary and Discovery Bay Ramsar site).

The Glenelg River, known as Bochara in Dhauwurd Wurrung, Pawur in Bunganditj and Bugara in Wergaia-Jadawadjali languages, is a significant feature in the cultural landscape of south-western Victoria. Bochara-Bugara-Pawur continues to be an important place for Traditional Owners, who have inhabited the area for thousands of years, using the rich resources available along the river and associated habitats.

The basin is one of Australia’s 15 listed biodiversity hotspots. The Glenelg basin contains 26 nationally listed threatened species and an additional 236 state listed species. Ten per cent of Victoria’s threatened species are found in this basin. Significant waterway species include the Glenelg spiny crayfish, Australian grayling, Gorae leek orchid and Wimmera callistemon.

The Glenelg River is an important attraction for recreation and tourism, and supports angling along its length.

The basin has been a focus for large-scale on-ground river restoration works over several decades, which have engaged stakeholders, including hundreds of landholders, across the catchment in a wide diversity of activities including:

- Riparian fencing and revegetation.

- Environmental flow delivery.

- Improving connectivity for fish and other aquatic species.

- Establishing recreational infrastructure.

- Estuary management.

- Weed control.

As a result, the Glenelg restoration project was awarded the Australasian Riverprize in 2013. Significant tributaries include the Wannon, Chetwynd, Crawford and Wando Rivers.

Hopkins Basin

The 9,985 km2 Hopkins Basin extends from the western parts of Ballarat in the north to the southern coastline. The Hopkins River is the major river. Other notable waterways include the Merri River. Fiery Creek/Salt Creek, Brucknell Creek and Mt Emu Creek are major tributaries of the Hopkins River. Both the Merri and Hopkins rivers have estuaries that connect to the ocean through the City of Warrnambool. The Hopkins River and its tributaries are popular fishing destinations for freshwater and estuarine species. Both the Merri and Hopkins are used extensively for other recreational activities like boating, birdwatching and walking.

The Hopkins Basin has been extensively developed to support agriculture. Despite this, habitats in the basin support 17 nationally listed threatened species and an additional 146 state-listed species. Significant aquatic species of the Hopkins basin include the south-western form of river blackfish and the Yarra pygmy perch. Significant Landcare and community works are a focus of the catchment, with river restoration works in the Brucknell Creek, Mt Emu Creek and other tributaries of the Upper Hopkins catchment.

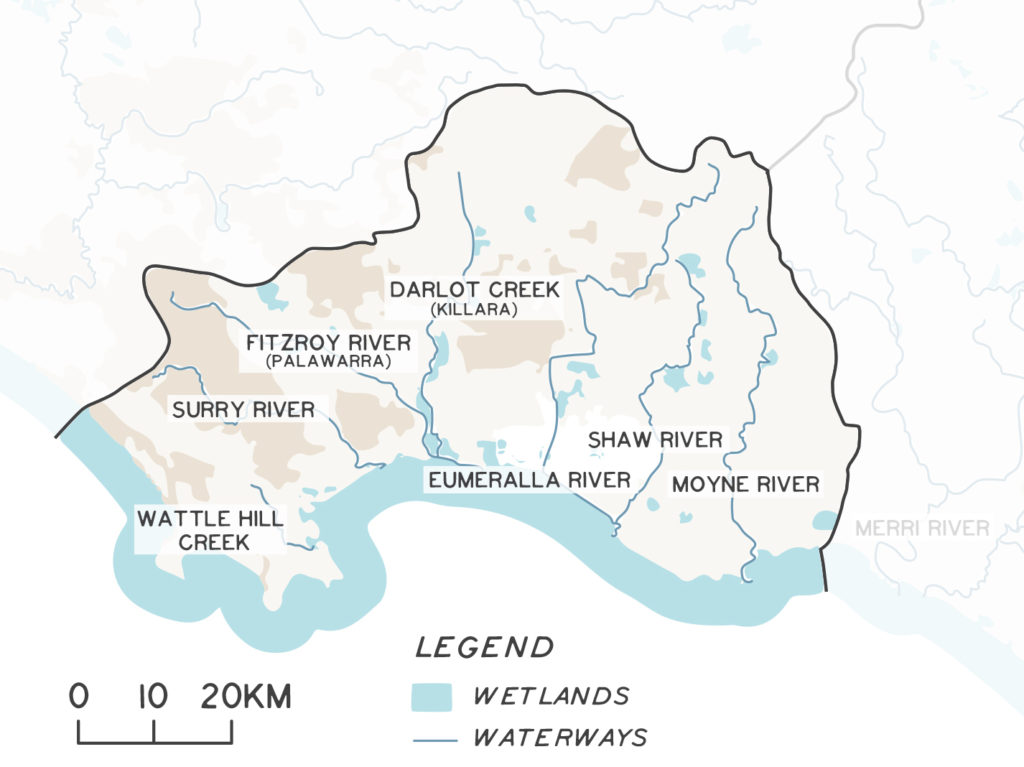

Portland Basin

The 3,983 km2 Portland Coast Basin features generally shorter river systems that drain towards the coast. The basin contains a number of important rivers and estuaries, including the Moyne, Eumeralla/ Shaw, Fitzroy and Surry rivers. The basin also supports the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, which includes Darlot Creek and the Fitzroy River. Budj Bim has World Heritage status linked to the quality of water in its waterways and its connection to the long history of aquatic system management by Gunditjmara people to farm and harvest Kooyang (short-finned eels). Rivers of the basin are popular for recreational and even commercial fishing.

The Portland basin includes 10 nationally threatened species and 128 state-listed species. Important species found in river systems in the basin include the Kooyang and the Glenelg spiny crayfish.

Assessment of current condition and trends

Rivers are dynamic environments that change daily, seasonally and annually. Healthy rivers are resilient systems that can maintain their function within naturally occurring ranges. River condition is a function of flow, water quality, geomorphology, aquatic species diversity and distribution, and riparian vegetation condition, among other factors.

There have been significant changes since the end of the millennium drought and as a result of climate change1,2. An extensive integrated program has been delivered across the region to improve river condition and health. More recently, monitoring has focused on measuring the long-term outcomes of river restoration and management activities at the site scale. For example, the Riparian Intervention Monitoring Program (RIMP) is a statewide, long-term intervention monitoring program that aims to evaluate and demonstrate responses of riparian land to weed control, revegetation and livestock exclusion3. There are RIMP sites scattered across the state. A resurvey of sites three years after management interventions showed, the following changes in vegetation condition:

- Total native vegetation cover increased ~2-fold.

- Native species richness increased ~1.5-fold.

- Planted and natural woody recruits increased ~ 9-fold.

- Woody weed abundance decreased to almost zero at most sites.

- Bare groundcover did not increase as found in unmanaged sites4.

Demonstrating Change

Water for Victoria has identified 36 priority flagship waterways across Victoria that will be improved through large-scale and long-term projects over a 30-year period. Conservation, restoration, threat management and communication activities in flagship areas are supported by robust monitoring, evaluation and reporting processes designed to clearly demonstrate the outcomes achieved from investment. Flagship waterway projects aim to demonstrate long-term change.

The Budj Bim Connections Flagship Waterway is the Glenelg Hopkins region’s first flagship waterway and includes the UNESCO World Heritage listed Budj Bim Cultural Landscape – incorporating Darlot Creek, the Fitzroy River and its estuary.

Budj Bim has the oldest known record of aquaculture in the world and is an important biodiversity hotspot in the region. It supports threatened aquatic fauna including Yarra pygmy perch, little galaxia, Australasian bittern, growling grass frog and Glenelg spiny crayfish.

Since 2015-2016 activities across the Budj Bim Flagship Waterway have been implemented in partnership with Traditional Owners and private land managers to improve waterway health. This has included hydrological restoration of wetlands, woody weed control, revegetation and protection of riparian areas through fencing. More than 700 community members have shared and learnt stories about the cultural and natural landscape through field days, training events and presentations. Extensive and entrenched willow infestations has been the greatest challenge and opportunity for the project. A long term monitoring, evaluation, reporting and improvement plan for the area has also been developed.

Managing the health of rivers requires an integrated approach across the whole catchment. Landholders have completed extensive works since the last RCS was developed to protect and enhance river health in the region including:

- Environmental flow management.

- Installation of fish hotels, snags and other and fish habitat.

- Widespread riparian fencing and replanting with native species, including throughout the tributaries.

- Sand extraction.

- Installation of off-stream watering points to remove stock from rivers.

- Installation of fishways and fish ladders.

- Removing barriers to fish movement and migration.

- Catchment erosion management.

- Management of stormwater and other discharges to rivers.

- Point source pollution management, including dairy effluent.

- Managing estuaries.

- Effective management of nutrients and their application throughout the catchment.

- Floodplain wetland management.

- Catchment revegetation and protection of remnant vegetation and wetlands.

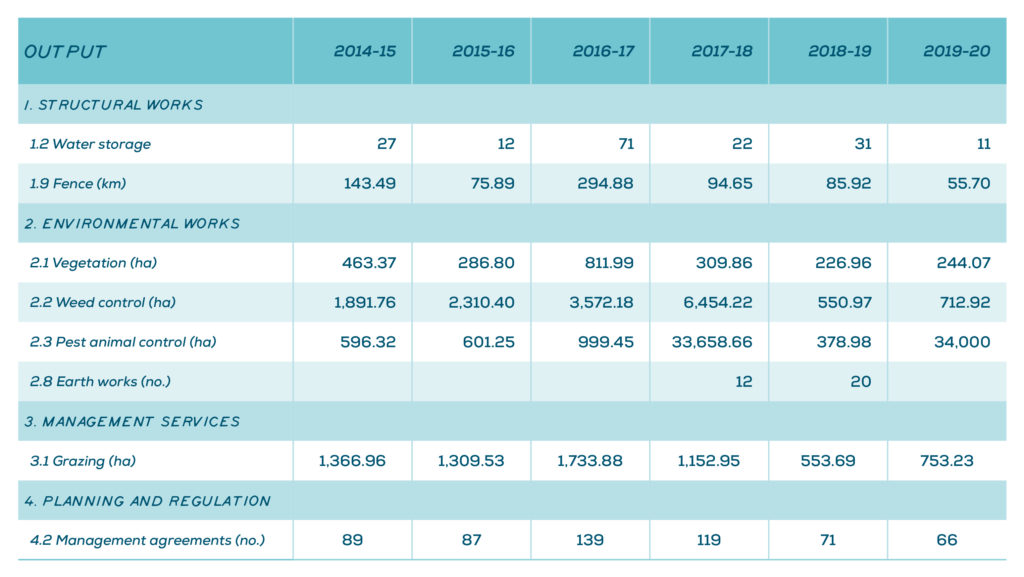

Figure 1 reflects efforts to protect or improve the condition of riparian lands, including fencing, weed control, revegetation and pest control across the Glenelg Hopkins region since 2014-2015. This data set is from internal tracking of outputs or activities that are delivered by or in partnership with CMAs through reporting of standardised outputs as per DELWP output data standards, 2015. They do not reflect effort delivered through other programs and self-funded landholder projects.

Fishway installation to support fish movement in river systems

Revegetation works along the Merri River

Fish hotels placed in rivers, such as the Merri, are improving in-stream habitat

Flow

Water flows into rivers from rainfall, local runoff and groundwater. Flow is a defining characteristic of rivers, streams, creeks, rivulets and gullies compared to other more static aquatic environments like wetlands and lakes. The volume, seasonality and timing of flow are the primary drivers of river health and influence a range of ecological, physical and chemical processes. Flow also connects the catchment as water moves downstream, while overbank flows provide an important connection between rivers, floodplains and fringing wetlands.

Flow redistributes the raw materials that underpin aquatic food chains. Ecological processes such as flowering, spawning, germination, dispersal and access to feeding areas can rely on flow-based cues. Flow is the main force that shapes rivers, moving silt, gravel and sand through the catchment. It is a significant driver of water quality and processes such as mixing, stratification, aeration and salinity.

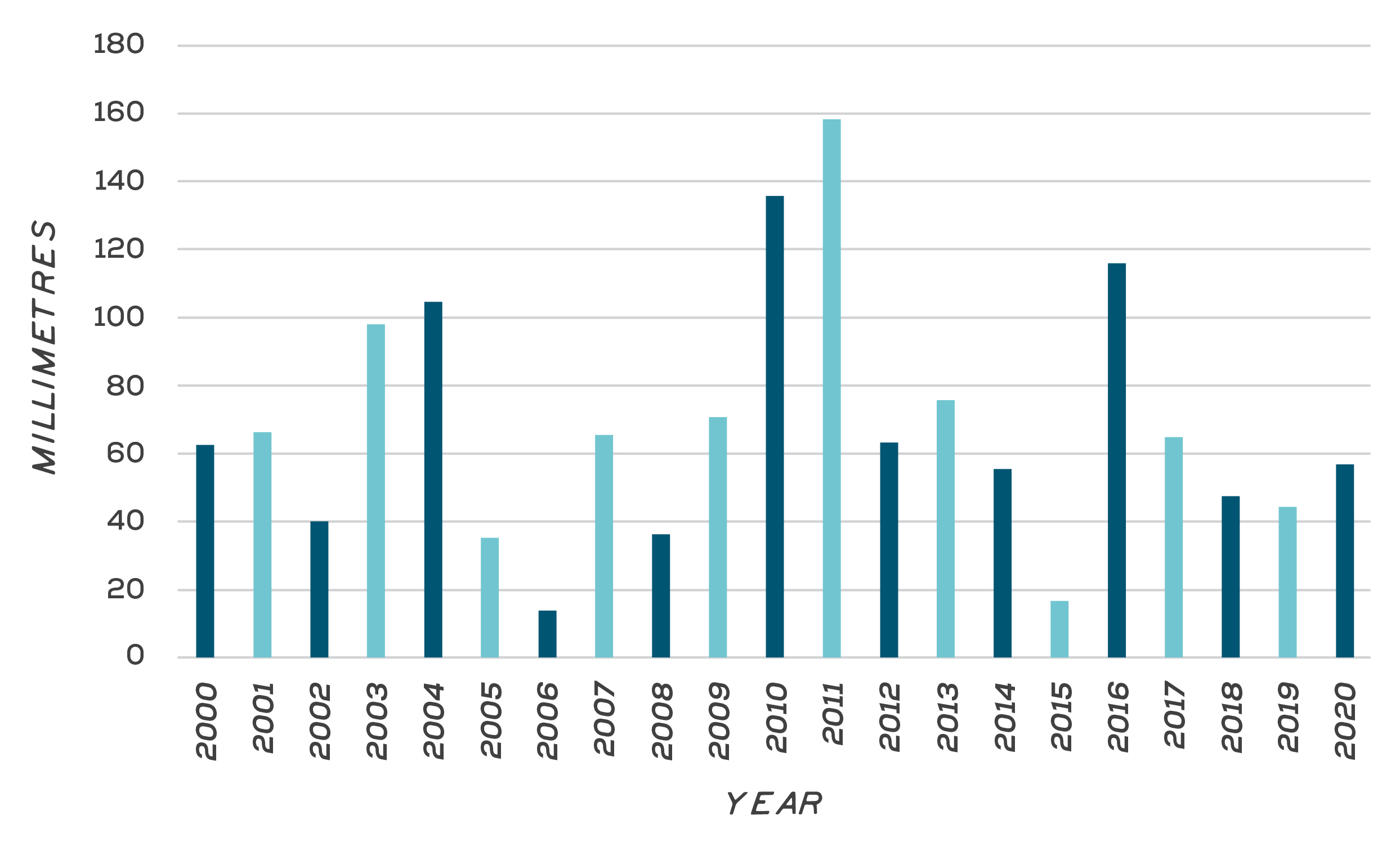

Flow is heavily dependent on rainfall, and there is well-documented evidence that small reductions in rainfall result in higher magnitude reductions in runoff. This rainfall-runoff relationship is not simple or static, but changes over time. The annual modelled river inflow in the Glenelg Hopkins region over time is shown in Figure 2.

The Glenelg River is the only river in the region with a managed environmental water entitlement. The entitlement includes managed water releases drawn from water storage to support environmental values downstream of Rocklands Reservoir. Carefully managed, regulated flows are used to support values including extraction and consumption, fish movement and water quality. In the Glenelg River, environmental water delivery has gone some way to countering the effects of both river regulation and climate change impacts, which has reduced natural flows downstream of Rocklands Reservoir. From 2010/11, regulated environmental water has made up more than 50% of the flow passing Rocklands Reservoir. Other rivers without large reservoirs have water sharing managed through a range of regulatory tools. These tools include passing flow rules at diversion points, limits on private dam construction, rosters and restrictions on when and how much water can be taken, and water trading rules.

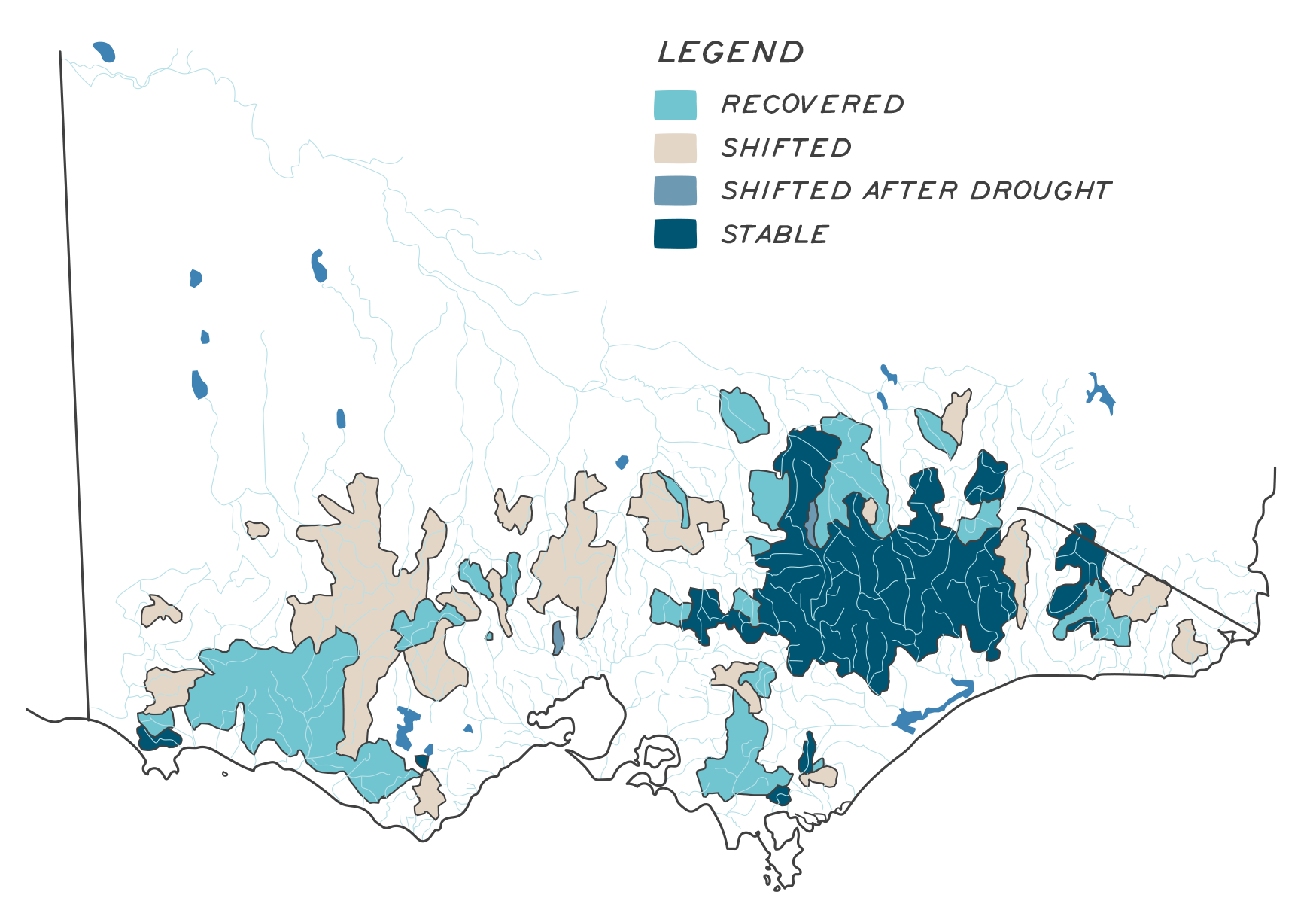

Victoria’s Water in a Changing Climate found that catchments in Western Victoria experienced shifted rainfall-runoff relationships during and after the Millennium drought5 . While some recovered with the end of the drought, many have not (Figure 3).

The report confirms that changing climate is having a long-term impact on the amount of water in the landscape that makes its way into waterways, including rivers. A significant step change in flow occurred in 1997 in south-eastern Australia, which cannot be explained by natural variability alone6. Analysis of average annual flow data comparing the period 1973–1996 to 1997-2019 supported this finding and indicated the following changes in flow volumes for the major basins:

- Glenelg Basin represented by Glenelg River at Dartmoor declined by 57%.

- Portland Basin represented by Darlot Creek at Homerton declined by 40%.

- Hopkins basin represented by the Hopkins River at Hopkins Falls declined by 60%.

Water quality

Water quality includes the physical, chemical and biological characteristics of water and sediments within rivers. Poor water quality can arise from point and diffuse sources of pollution, natural biological processes and the degrading effects of human interference in the landscape. Water quality impacts can be acute (arising from an event), or chronic (resulting from longer-term changes and processes).

Streamflow also drives some elements of water quality. For example, nutrients and turbidity are typically higher during high-flow events because soil, agricultural fertilisers and farm effluent are washed into rivers. Low dissolved oxygen is often associated with very low flow events during high temperatures, and when blue-green algae die off. Low dissolved oxygen can also follow floods or bushfires when large amounts of ash and debris are deposited in the river, where rapidly increasing populations of bacteria use oxygen as they decompose organic matter. High salinity can occur during wet climate sequences as high watertables increase salty groundwater discharge and dryland salinity. Water acidity can change rapidly when potential acid sulphate soils, such as peat deposits, dry – this can trigger a harmful chemical process.

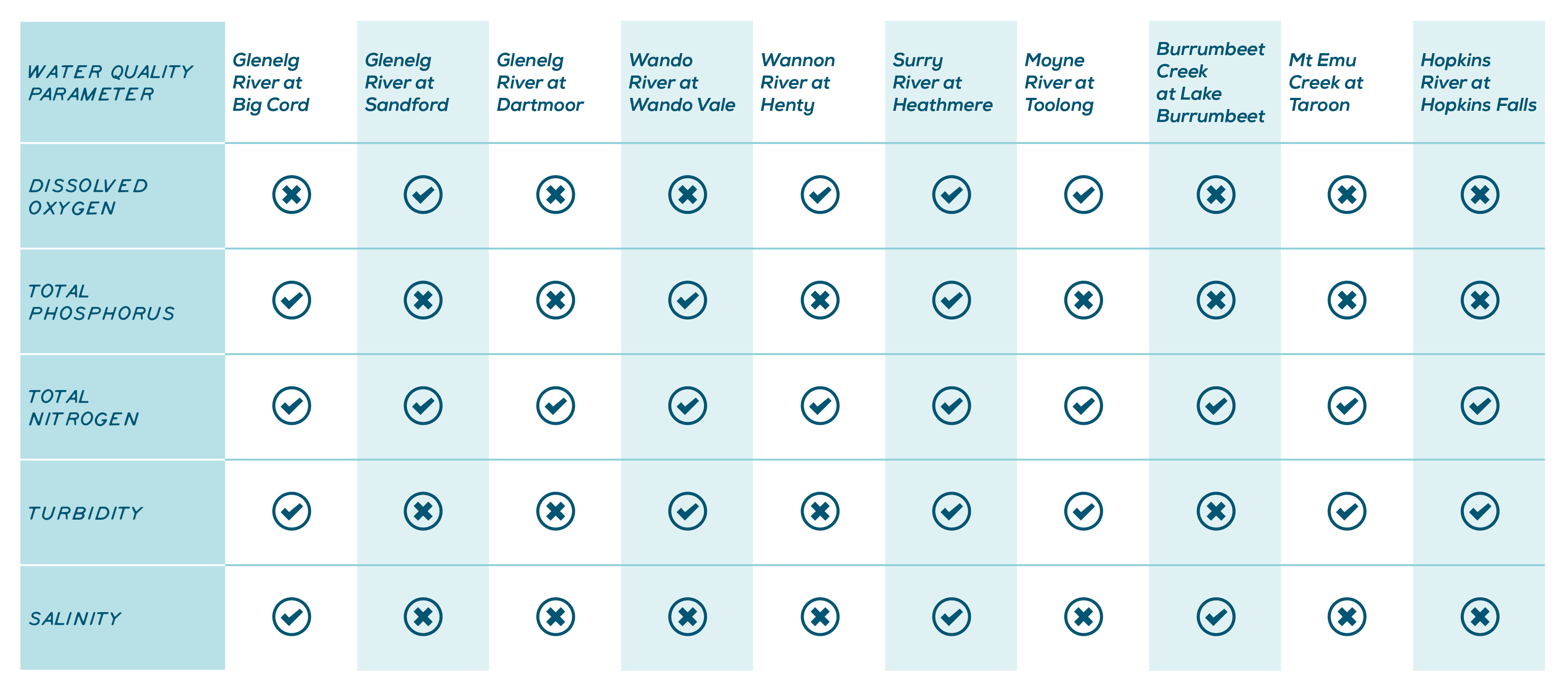

Stock in waterways add additional nutrients that impact water quality

The State Environment Protection Policy (SEPP Waters) defines environmental quality indicators and water quality objectives for all types of waterways. The objectives set levels for each water quality parameter to protect the beneficial uses of water. Beneficial uses can include purposes such as ecosystems, human consumption, agriculture, aquaculture, industry and commerce, recreation and Traditional Owner cultural values. Data has been analysed in each basin to determine whether the water quality exceeds a selection of the SEPP (Waters) maximum objectives in a subset of rivers. As shown in Figure 4, most rivers exceed at least one environmental quality objective, indicating that the waterway’s beneficial uses may be at risk.

To identify trends over time, water quality under different flow conditions (low, medium and high) were assessed across the region’s rivers. The analysis of data from 1990 to 2019 shows that in most rivers and across most flow conditions water quality is worsening. In some places the change has been dramatic. It is unclear what is driving this change, however, it is likely related to the rapid intensification of land use to high input agricultural systems.

Algal blooms are just one example of the way that poor water quality impacts the values of waterways. Algal blooms form through the excessive growth of a family of naturally occurring cyanobacteria found in the region’s rivers and wetlands. When conditions are suitable, they form dense blooms to a point where they discolour the water, form surface scums, produce unpleasant tastes and odours, affect fish, cause rapid changes in dissolved oxygen and release toxic substances. Algal blooms can make water unusable for humans and toxic for aquatic life. When blooms die, the decomposition of algae cells depletes oxygen and can cause the sudden death of aquatic organisms, including fish.

River morphology and physical form

Morphology describes the form and shape of a river channel. The shape, slope and material in the river channel and adjacent floodplain are influenced by biological and hydrological processes in the river. Rivers tend to scale to their inputs of water and sediment. As a river flows downstream it conveys more water more often, and becomes broader and deeper as a result.

The movement and deposition of sediment influences downstream river health. Although sedimentation is a natural part of river system processes, the amount of sediment can be increased by animals disturbing riverbed and banks. Plants stabilise sediments and create conditions that support sediment deposition. Clearing of deep-rooted vegetation and erosion in the catchment increases silt and sediment washing into rivers.

Major threats and drivers of change

Changes to water availability

Major water diversions occur at Rocklands Reservoir and Moora Reservoir, with smaller water harvesting at the Wannon diversions, and small weirs in the Victoria Valley and on the upper Fiery Creek. Water diversions from rivers in the region are capped to prevent further allocation. Allocation caps are based on historical use, climate and hydrological data.

Farm dams harvest water within the catchment and impact water availability to rivers, particularly during dry (low flow) conditions. The number of farm dams in the region has increased over time. In the Coleraine area, for example, the number of farm dams has increased by more than 80% since the 1970s, while in the Woorndoo area the increase is more than 25%8. Limits on farm dams have been established to work toward equitable access to water for all users, including the environment. However, enforcement is challenging.

Land use change

Land use in 80% of the region has historically revolved around agricultural production. This continues to be the case, but the diversity of types of agricultural products is evolving as rainfall patterns change, technologies evolve and markets drive innovation. For example, timber plantations in the Glenelg catchment regions of Bahgallah, Dartmoor, Dergholm, Hotspur and Nareen increased by 730% between the 1990s and 2016 from 1,421 ha to 10,354 ha9. Actively growing plantations have high water demands, impacting groundwater and local surface water availability.

Some land uses affect the condition of rivers more than others. More input intensive production may affect the amount of nutrients, effluent or pollutants flowing into rivers. Water availability and flow may also be affected by rapid changes in land use including the conversion from grazing to cropping, from cropping to irrigated production or from grazing to plantation. Expansion of urban areas and development along rivers change water availability, runoff and stormwater management, increase pollutants and litter, and clearance of streamside vegetation.

Native habitat clearance and conversion

Clearance of remnant habitats within the catchment (including riparian areas and on hill slopes and gullies) impacts the rivers by increasing sediment loads, reducing biodiversity values and connectivity, and changing flow regimes and the speed at which water moves. Riparian vegetation keeps water temperatures lower, stabilises riverbanks during floods, filters water and traps sediments, and provides a variety of habitats, shelter and food sources for the many terrestrial and aquatic species that use rivers.

Wetland drainage has been widespread within the region, resulting in the loss of wetland habitats. The loss of floodplain wetlands, and their ability to hold water in the landscape, particularly impacts rivers – changing flow dynamics and increasing peak flows in rivers, which can exacerbate downstream flooding. Wetlands provide a vital filtering function to rivers and are often described as the ‘lungs’ of the river ecosystems.

Outlet for environmental water releases from Rocklands Reservoir along the Glenelg River

Electrofishing to control carp – a major threat to regional waterways

Land clearing contributes to gully erosion

Climate change

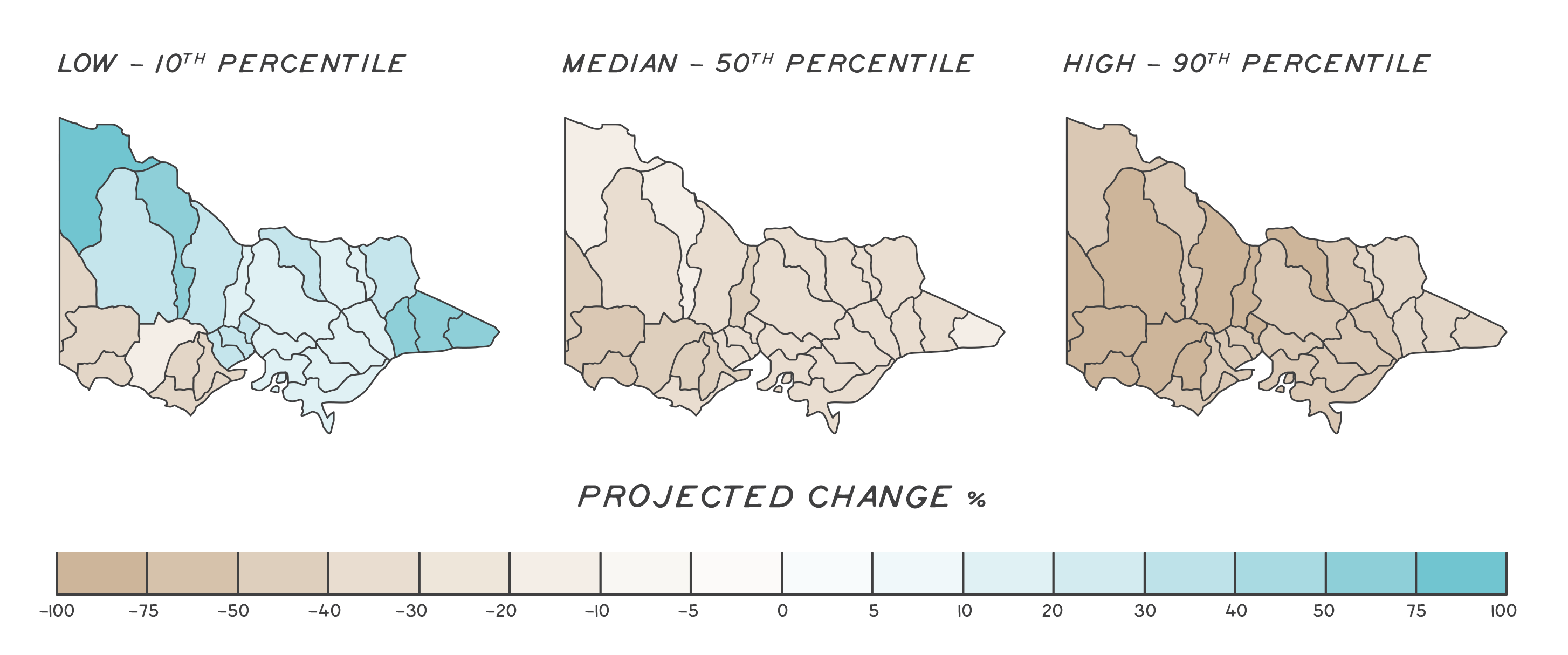

The region is already experiencing the impacts of reduced rainfall and changed seasonality due to climate change and this will continue to pose a threat to rivers and the species they support. A direct impact of reduced rainfall is reduced streamflow. Streamflow declines predicted by low, median and high climate change models10 are shown in Figure 5. The Glenelg Hopkins region is predicted to experience among the largest streamflow declines in the state under a range of modelled climate change scenarios. Extreme rainfall events are projected to increase. Reduced average annual flow and increased frequency of extreme events will mean that rivers and their ecology will be significantly modified by climate change11.

The effects of climate change will be particularly challenging for species that require permanent water for survival (e.g. fish, platypus, crayfish). Prolonged cease-to-flow events will challenge the ability of those species to survive long term. Because of this, protected areas will become increasingly important as they provide refuge, reduce overall sensitivity and increase adaptive capacity across the landscape12.

Pests plants and animals

Pest plants occur in both riparian and aquatic zones of rivers. They are widespread along rivers of the region and range from long-lived, entrenched species like willows, poplars, buckthorn, spiny rush and blackberry to short- lived agricultural annual weeds. They change river function, including fire regimes, and impact the biodiversity values associated with rivers while failing to provide adequate food or shelter to native species.

Aquatic weeds generally emerge as escaped garden pond and aquarium species (e.g. water lilies). The region has few established infestations, but managing aquatic weeds requires ongoing vigilance, early treatment of outbreaks and ongoing education programs.

Pest fish and animals impact in several ways. The widespread distribution of exotic and non-endemic Australian predatory fish species throughout rivers and wetlands affects local fish, frog and invertebrate numbers, disrupting food chains and increasing predation. Some species, like carp, also physically alter rivers through the way they feed, uprooting aquatic vegetation, increasing turbidity and mobilising nutrient loads. Terrestrial pest animals also impact rivers and their values. For example, increasing feral pig numbers result in the disturbance of river beds, the loss of aquatic vegetation, and increased nutrients and sedimentation. Foxes widely impact on the survival of native species, including waterbirds.

Outcomes and priority management directions

Outcomes and priority management directions have been developed to show what success looks like for integrated catchment management (ICM) across the Glenelg Hopkins region. Below are the 20-year (long-term) outcomes for rivers. Within these are the proposed six-year outcomes and priority management directions to be achieved within the life of this strategy. The priority management directions are identified across the adaptation pathway stages of resilience, transition and transformation (see RCS approach for more information). Lead and key partners involved in delivery are also outlined.

By 2042, Traditional Owner communities are decision makers and provide strategic leadership for River Country

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Owners rights, interests, obligations and access to water, including cultural flows, are acknowledged and protected. | Traditional Owners identify and increase awareness of their rights and access to water entitlements. Understanding and awareness of Cultural Flows is increased across Traditional Owner communities. Traditional Owner Groups influence the Seasonal Watering Plan for the Glenelg River to maximise Aboriginal environmental outcomes | Traditional Owners are supported to educate their communities and build awareness of their rights and access to water. Traditional Owner rights and access to water are communicated with the broader community. Understanding and awareness of Cultural Flows is increased across agencies, authorities and the broader community. Traditional Owners acquire water licenses and pursue other avenues to access water. | Traditional Owners hold their own water entitlements. Traditional Owners lead decisions about environmental and cultural watering. Traditional Owners manage water entitlements to achieve their identified outcomes and benefits. Traditional Owners influence legislation and policy to support cultural values around rivers and floodplains. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| Traditional Owner communities have the capacity, knowledge and authority to look after river Country including cultural flows. | Traditional Owners undertake projects to record, document and implement their cultural practices and knowledge for the management of river Country. Two-way knowledge sharing between partners is promoted. Traditional Owners collaborate in regional planning processes through strengthened partnerships. Traditional Owner Country Plans include water related priorities and actions that support the management of River Country. | The broader community is informed about cultural practices and knowledge where appropriate. Two-way knowledge sharing between partners is prioritised. Education and capacity building opportunities are provided for Traditional Owners around scientific and ecological management of rivers and floodplains. | Traditional Owners are leading regional planning processes for looking after River Country. Traditional Owner communities are reinstating cultural practices and knowledge. Traditional names for rivers and other waterways are reinstated. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

By 2042, the condition, function and resilience of priority rivers and their floodplains are maintained or improved

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The community has increased knowledge and capacity to collaborate on river and floodplain management. | Raise the awareness of the community about river and floodplain values and management. Provide the community with opportunities to be involved with riparian and floodplain management decisions. Improve understanding within the community about cultural values associated with rivers and flow. Support landholders to manage riparian zones and undertake another assets that protect river and floodplain health by providing technical advice, funding and other requirements. Implement the actions in the Glenelg Environmental water communications strategy (2020-2024). | Focus community education on values, expectations and understanding of change due to climate. | Develop an education and prioritisation framework for maintaining environmental and cultural flows. Advocate for appropriate flow allocation at strategic water resource reviews. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Wannon Water, DELWP, Traditional Owner Organisations, Parks Victoria, Nature Glenelg Trust, Landcare Groups, Victorian Fisheries Authority |

| Habitats for key regional indicator species are managed to ensure that their regional population and distribution is at least maintained. | Identify key regional indicator species, including those that are culturally and recreationally significant, and utilise existing decision support tools to identify actions that will maximise benefit to habitats. Protect existing high quality habitats and increase the connectivity of rivers by removing barriers and increasing native riparian revegetation. Protect upstream sources of woody debris and maintain diversity of stream structure, including reinstating instream habitat. Support development and implementation of the National Carp Control Plan. Control key aquatic pest plants and animals in rivers, including Carp and Mexican water lily, below critical thresholds. Implement strategic sand extraction in accordance with best practice methodologies. | Identify emerging pest plant and animal species and infestations and implement control programs. Establish eDNA monitoring of rivers to identify the distribution of key species. Identify critical biomass threshold for carp distribution in the Glenelg River. Identify drought refuges in rivers and implement actions to improve their resilience and function under changed climate scenarios. | Establish on-going and regular monitoring program for select indicator species. Implement adaptive actions in response to emerging information, monitoring and observation of climate change impacts. Create new drought refuges in sand-affected rivers by implementing riparian stock exclusion and riparian revegetation. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Wannon Water, DELWP, Traditional Owner Organisations, Parks Victoria, Nature Glenelg Trust, Landcare Groups, Victorian Fisheries Authority |

| Progress is made towards delivering on the interim water quality targets developed for the Glenelg Hopkins Regional Waterway Strategy. | Develop interim water quality targets as part of the renewal of the Glenelg Hopkins Waterway Strategy. Undertake catchment and riparian works (riparian restoration, revegetation, instream habitat, erosion control, alternative land use etc) to reduce sediment loads and nutrient transport. Provide incentive and education programs to encourage catchment management that improves water quality. Continue monitoring of water quality. | Implement programs (including Integrated Water Management, Water Sensitive Urban Design) to improve the quality of water discharged to rivers from urban stormwater. Support the uptake of alternative nutrient use and land management options (precision delivery, nutrient retention basins, effluent management, stock exclusion from rivers, different crop types, sowing patterns etc) that reduce nutrient run off to rivers. | Industry innovation programs or market drivers encourage new agricultural industries with less reliance on chemical inputs. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Local Government, Wannon Water, Landcare groups, Industry groups, Environment Protection Authority, local land managers, |

| The management of river hydrology is improved. | Continue to prioritise the delivery of environmental water to the Glenelg River consistent with relevant climate scenarios. Identify and prioritise waterways for updated flow studies. Support Integrated Water Management projects that provide for cooperative management of water (including discharges) to improve sustainable use. | Complete flow studies and update relevant local management rules to manage take and use under existing and low flow conditions (including under climate change scenarios) to meet needs of environment and adequately balance other uses. Contribute to the review of water resource availability and ensure allocation protects river health. Build cultural flows and traditional knowledge into flow management approaches. Build a more refined understanding of the value of different sequences of flows (e.g. 2 freshes vs 3, longer freshes vs shorter, timing) for key species. | Identify key indicator variables and resilience thresholds for rivers and use to improve management of priority rivers. Restore geomorphology of drained and incised rivers. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Water Authorities, Traditional Owner Organisations, local land managers |

| The condition and connectivity of rivers and riparian areas continues to increase, supporting the diversity of habitats associated with rivers and their floodplains. | Restore riparian vegetation extent and condition by reducing stock access, controlling pest plants and animals and restoring native vegetation along waterways throughout the catchments Set targets for length of waterway to be fenced and revegetated to meet key thresholds for each major river system Engage with landholders to improve understanding about the importance of riparian management to river and ecosystem health Remove or overcome priority fish barriers Identify river reaches with a lack of instream habitat and install in priority locations | Review environmental significance overlays (ESOs) in LGAs with priority ecological communities lost to land use change Increased education about compliance, values and landholders responsibilities Establish effective cross agency compliance actions Support the development of waterway and floodplain protection overlays and planning guidelines that recognise and protect the values of riparian ecological communities | Investigate the role of vegetated riparian zones on improved water quality in local rivers and utilise findings to guide community education, planning and management Partner with peak industry bodies to support the delivery of industry environmental commitments | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Local Government, Traditional Owner Organisations, Parks Victoria |

By 2042, flood risks are reduced through improved flood intelligence and mitigation

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80% of the Glenelg Hopkins Regional Floodplain Management Strategy priority management actions are implemented. | Implement the actions identified in the Glenelg Hopkins Regional Floodplain Management Strategy 2018. Update flood management information and provide to urban planners, including flood studies. Utilise new data (e.g. scientific investigations, LiDAR) to refine planning on floodplains incorporating climate change impacts such as extreme events. Ensure that recreational infrastructure on rivers is designed to allow for flooding (e.g. floating rather than fixed structures). | Build the natural fluctuations and movement of water across floodplain into all new development controls. Support the development of waterway and floodplain protection overlays and planning guidelines. | Restore geomorphology of drained and incised rivers and wetlands. Cultural value assessments are included as standard practice when undertaking regional flood investigations and assist Local Government Authorities in the assessment for urban flood investigations. Traditional Owners manage water entitlements to achieve their identified outcomes and benefits. Traditional Owners influence water laws and policies so that water laws and policies support cultural values around rivers and floodplains. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | VICSES, DELWP, Local Government |

Key strategies and plans that relate to the delivery of river outcomes include:

- Water for Victoria

- Victorian Waterway Management Strategy

- Glenelg Hopkins Waterway Strategy

- State Environment Protection Policy

- Freshwater Fisheries Management Plan

- Victorian Floodplain Management Strategy

- Glenelg Hopkins Regional Floodplain Management Strategy

- Glenelg Hopkins Climate Change Strategy

- Integrated Water Management Framework for Victoria

- Central Highlands, Great Coast and Wimmera Integrated Water Management Strategic Directions

- Regional Riparian Action Plan

- Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Landscapes Strategy

- Growing What is Good Country Plan, Voices of the Wotjobaluk Nations

- Meerreengeeye ngakeepoorryeeyt, Eastern Maar Country Plan

- Ngootyong Gunditj Ngootyong Mara South West Management Plan

- Paleert Tjaara Dja, Let’s make Country good together 2020-2030, Wadawurrung Country Plan

- Warrnambool 2040

- Glenelg Shire 2040, Our Future Together

- Moyne 2040