The Glenelg Hopkins region supports a permanent population of 137,000 with year-round tourism adding significantly to this number. The community includes people who live, work and visit or feel a connection to the region. Major cities and towns include Warrnambool, Hamilton, Portland, part of Ballarat, Ararat, Koroit, Port Fairy and Terang. The region attracts large numbers of visitors to its world-class tourist attractions and boasts a variety of educational and research institutions.

Integrated Catchment Management (ICM) recognises that people and their livelihoods rely on the health and productivity of landscapes and communities, and land managers need to be empowered to be directly responsible for sustainably managing the region’s natural resources. The whole community has a critical role to play in ICM in the region – from farmers to policy makers and planners. They need to work collaboratively to improve the management of catchment resources in the face of ongoing change1.

Glenelg Hopkins CMA leads and manages the development of the Regional Catchment Strategy (RCS), but it is partnerships with community, individuals and organisations within the region that are the foundation for effective delivery of the RCS. The RCS outlines a commitment to partnership and collaborative effort that encourages and supports the participation of the community, landholders and resource managers in land protection and catchment management.

Key contributing groups have legislative, corporate and social responsibilities to oversee ethical and sustainable resource management. They include Australian, Victorian and local governments; Glenelg Hopkins CMA; land, sea and water managers; industry and industry bodies; Traditional Owner organisations; community groups and volunteers; business, research and education organisations; and non-government organisations (NGOs). Strong community support enables these groups to appropriately plan, resource and act on priorities. Traditional Owners have cultural rights and obligations to look after Country.

This strategy aims to support the community in guiding collaborative and outcome-focused action. Planning and implementation of ICM programs should maximise opportunities for community engagement and leverage work already undertaken by regional partners.

Tree planting along the Grange Burn, Hamilton

Gunditjmara Traditional Owners and RUIL staff (Research Unit for Indigenous Language, The University of Melbourne) recording traditional bird names for the Part-parti Mirring-yi app (Shane Bell, Sherry Johnstone, Ada Nano, ‘Locky’ Eccles, Joel Wright, Janice Austin, Roslyn Clarke-Britton and Debbie Loakes)

Photo: Jenny Green

Land managers are key to a healthy and sustainable catchment

Photo: Southern Grampians Shire

Assessment of current condition and trends

Socio-economic trends

Some areas of the Glenelg Hopkins Region have experienced strong population growth over the past 30 years and others have declined, resulting in slow to non-existent population growth for the whole region2.

Ballarat accounts for the strongest population growth, particularly between 2006 and 2011, which triggered development in small peri-urban towns around Ballarat, such as Smythesdale, Snake Valley and Learmonth3.

More than 35,000 of the region’s residents reside in Warrnambool, and strong population growth is occurring in the city.

Apart from Dunkeld, which has benefited from its proximity to the Grampians and Mortlake, the populations of smaller inland towns have declined. There has been modest population growth in coastal communities, particularly Port Fairy and Allansford.

The age demographic within the region follows the pattern across Victoria, with a gradual increase in the share of population aged over 65. This is a result of the general ageing of the Australian community and by the migration of the young away from rural areas. Towns within the region with a younger age structure are found on the outskirts of Ballarat and Warrnambool. The towns with an older age composition are within the region’s agricultural zone.

Projections for the region indicate the shift across age groups is likely to continue4. This ageing of the population has the potential to affect regional economic productivity and labour markets, and increase pressure on the region’s social system.

Across Victoria, including the Glenelg Hopkins region, people with lower incomes are overrepresented in small inland towns. Higher-income earners are most likely to be found on the outskirts of large regional cities such as Ballarat and Warrnambool. A point of difference within the region is the large section of the rural hinterland (around Hamilton, Balmoral and to the south-east of Warrnambool) that is relatively prosperous compared to many other parts of rural Victoria.

The region is recognised as predominantly agricultural, however, industries such as health services, education and training or retail lead employment statistics in several LGAs. The structural ageing trend has increased employment in health in most towns in the region. Health and education are the major employers in all towns in the Glenelg Hopkins region, except in Ararat and Portland where manufacturing is the major employer. Generally, primary industry employment dominates the labour market in the inland part of the region. In the longer term, the trend in the slow expansion of farm scale and reduction in the number of farm businesses is likely to continue5. The rate and direction of change will be influenced by the performance of commodity markets.

In addition to the ongoing forces of demographic change, there are potential future shocks that will affect the region’s industries. These impacts include the ongoing effects of COVID-19, changes in demand for export goods (such as wool), and changes in energy and climate policy.

Wetland field day

Landholder engagement

Glenelg Estuary Litter Cleanup Day, Glenelg estuary, Nelson

Traditional Owner groups

Barengi Gadjin Land Council, Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation, Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation manage the region’s cultural and environmental values through Indigenous Protected Areas, jointly managed National Parks and private land holdings.

The recognition of Traditional Owner groups has occurred nationally through Native Title and within Victoria as Registered Aboriginal Parties and through recognition and settlement agreements. These processes have been strengthened by the recent self-determination policy and legislative changes that outline Traditional Owner engagement across all integrated catchment management activities. The incorporation of Traditional Owner knowledge into ICM projects has been increasing. Programs such as Caring for our Country and the National Landcare Program have supported this process through on-ground projects with groups within the region. Australia’s Strategy for Nature sets objectives around respecting and maintaining traditional ecological knowledge and stewardship of nature to ensure this trend continues.

Volunteering, community participation and community organisations

One of the most important mechanisms to support the delivery of the RCS is volunteerism, both formal (organised activities and organisations) and informal (such as collecting and removing rubbish when you visit a park or simply the inclination to make a more sustainable choice or change behaviours). Through ‘friends of’ groups, as well as organisations like Landcare and Coastcare, volunteers help to enhance and protect Victoria’s environmental assets.

The Glenelg Hopkins region’s Landcare program has been operating for 32 years and currently has five Landcare networks and 108 Landcare Groups. A further 49 community-based natural resource management groups are active in the region. The Victorian Landcare Gateway shows more about groups in the region and across the state.

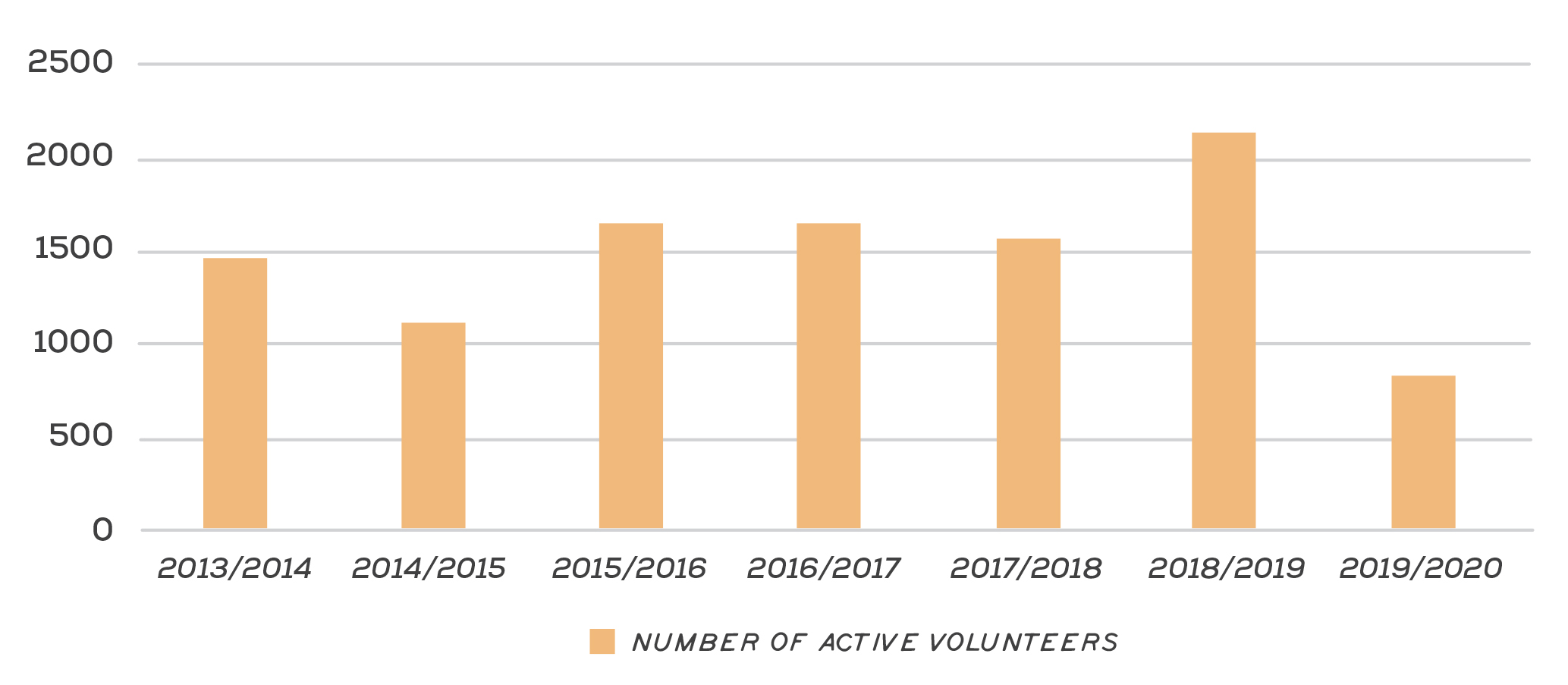

For the past 12 years, groups have been completing a ‘group health survey’, undertaken as part of the Victorian Landcare Grants delivered by Glenelg Hopkins CMA. The survey provides a basic snapshot of how groups feel they are performing and allows them to highlight future priorities and any challenges being faced. Groups are asked to describe their status: trail blazer, rolling along, moving forward, struggling and just hanging on. The survey data is used to develop a ‘group health score’ out of 5 for each year (Figure 1). The total number of Landcare group members is also captured during the group health surveys (Figure 2), and their activity over the five years from 2015-2016 to 2019-2020 (Figure 3).

Over the 12 years, the group health score is consistent, with a difference of only 0.39 between the highest score of 3.54 in 2018-2019 and the lowest score of 3.15 in 2010-2011. The percentage of groups reported as thriving or strong has peaked and troughed across the 12 years with a range from 35% in 2010-2011 to 58% in 2018-2019.

from 2015-16 to 2019-20

Groups identified challenges such as administrative burden, attracting group members, generational change and volunteer burn out. These challenges align with those faced within the volunteering space across Victoria6. Some priorities for the region’s groups are vegetation protection and enhancement, pest plant and animal control, sourcing project funding, threatened species protection and waterway protection.

In addition to Landcare there is a broad range of environmental volunteer work in the region. The challenge is trying to quantify the substantial ecological, social and economic outcomes for the communities in which they operate7. The Victorian Government’s Volunteering Naturally initiative identifies seven broad categories to capture the primary activity that groups undertake: caring for landscapes, wildlife rescue and rehabilitation, sustainable living, recreation/nature experiences, citizen science, advocacy and networks/other. The initiative also highlights the range of reasons that people participate in environmental volunteering, such as local place focused, nature-based recreation, issue driven and species focused.

Some examples of the diverse range of environmental volunteering activities in the region are CFA volunteers burning roadsides, Good Will Nurdle Hunting8, community coastal monitoring, bird monitoring and whale recording.

Community-driven industry groups play a significant role in shared learning, local and regional connection, and innovation. Groups such as Southern Farming Systems, the Grassland Society of Southern Australia and Perennial Pasture Systems work with the region’s landholders to build capacity, share knowledge, and undertake demonstrations and investigations.

Non-Government Organisations

Non-government and not-for-profit organisations play a pivotal role in delivering significant on-ground works, advocacy and planning, and in the social dynamic of the region. These groups traditionally have strong links with community and many provide opportunities for volunteering. Across the Glenelg Hopkins region, these groups range from environmentally focused groups such as Nature Glenelg Trust and Birdlife Australia to those with an industry focus like WestVic Dairy and Meat and Livestock Australia. These groups operate in the space between government organisations and community-based groups. They provide a strong voice for issues relevant to the region and a collective effort. Many non-government groups attract both philanthropic and government funding to the region.

Aunty Eileen Alberts talking to community about Gunditjmara Country

Dan Tehan, Anthony Watt (CFA) and David Jamieson (Previous Woorndoo CFA member) discuss importance of CFA role in roadside burning

Fyke net fish survey, Harrow

Wellbeing and tourism – catchment recreation groups

There is an increasing recognition that a thriving environment and connection to nature play a significant role in the health and wellbeing of people and communities9. The Glenelg Hopkins region provides a variety of nature tourism attractions visited by those living within and outside the region. The importance of health and wellbeing is reflected in the increase in integrated catchment management projects with recreational outcomes. Within the Glenelg Hopkins region this is most applicable along the coast, in towns such as Warrnambool, Port Fairy and Nelson.

Recreation fishers, angling clubs and local ‘friends of’ groups have been a collaborative cornerstone for recent projects to reinstate native fish habitat, waterway connectivity, improve riparian health and extend the reach of engagement activities. Recreational users of waterways, in particular anglers, have a strong and supported network through membership of VRfish (the peak body for anglers), the Victorian Fisheries Authority, OzFish, Fishcare and CMAs. Finding shared goals with recreation groups such as angling and field naturalists has produced effective partnerships and is a positive trend for the region.

Education

Beyond the regional network of primary and secondary schools, the region boasts a range of vocational training and tertiary education facilities. Having these facilities regionally based increases the likelihood of retaining local people wanting to pursue further education. Courses focused on the larger employment sectors of health and agriculture mean that there are clear pathways for employment.

Regionally based tertiary facilities also act as a hub for research and innovation. This provides the opportunity for applied research in direct response to specific environmental issues. Regional research capability can also enhance knowledge of social issues and contribute to policy and planning10.

Government

Government departments at a state and federal level play a significant role in setting policy relevant to the delivery of the RCS, ICM more broadly, and the management of public land assets. They engage with community and partner organisations across the region to consult on key policies and programs.

Local governments have an important influence on ICM through their responsibilities for local land use planning, development approvals, stormwater management planning and works, and management of publicly owned reserves. They also provide a variety of services, such as road construction and maintenance, waste management, pest control, community education, community grants and support for volunteer groups. Councils with significant jurisdiction across the Glenelg Hopkins CMA region are: Ararat Rural City, Ballarat City, Corangamite Shire, Glenelg Shire, Moyne Shire, Pyrenees Shire, West Wimmera Shire, Southern Grampians Shire.

Woodland bird monitoring, near Dunkeld

Anglers and recreational fishing groups are helping to improve waterway and riparian health

Community tree planting

Partnerships

The breadth of people and organisations involved in catchment management means a collaborative approach to managing the landscape is vital. Building partnerships and integrating effort is important in delivering Integrated Catchment Management, and providing a range of economic, social and recreational benefits for our local communities.

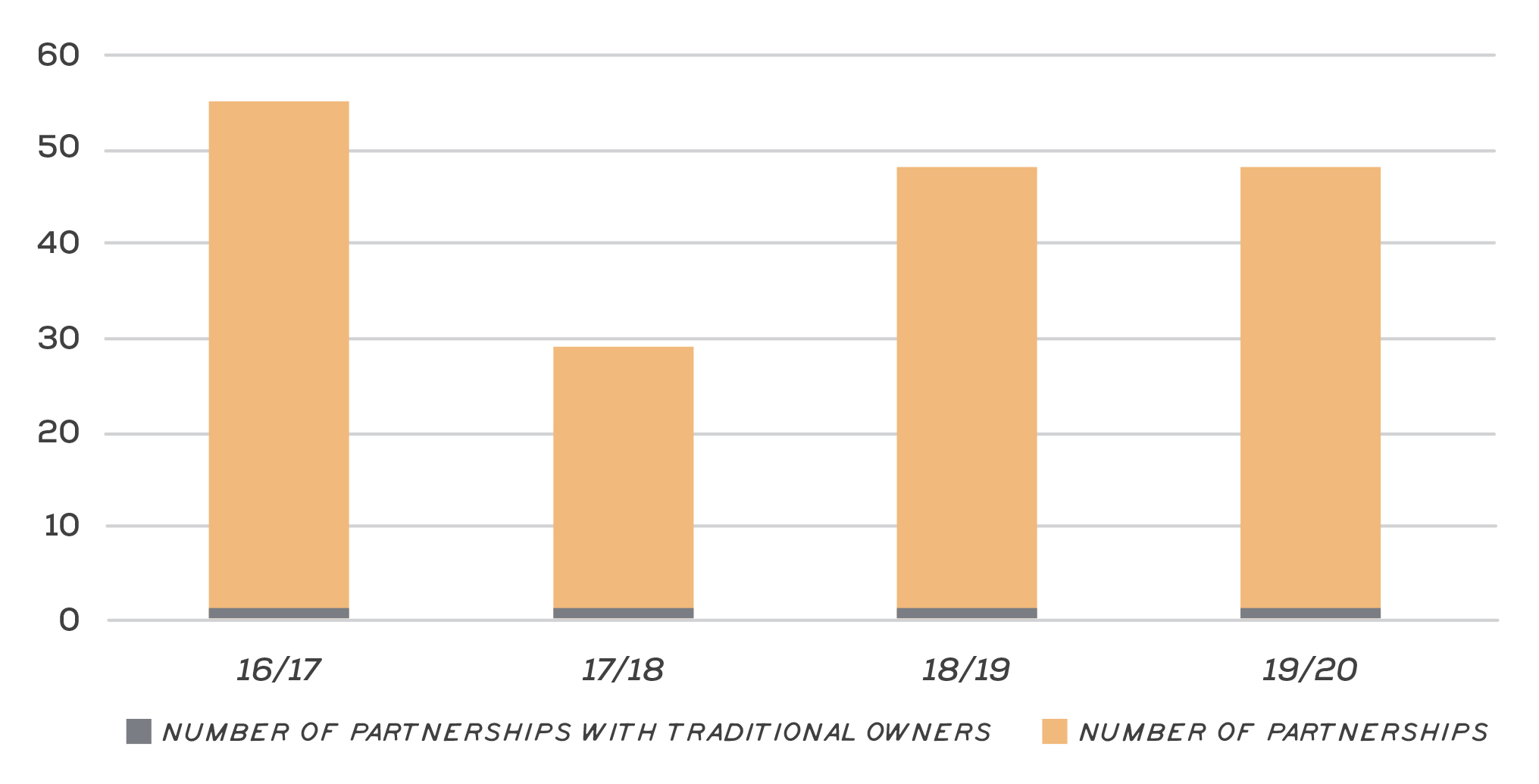

The graph below details the formal partnerships established, modified, or maintained between organisations and individuals, under CMA initiatives (Figure 4 – This data set is from internal tracking of outputs or activities that are delivered by or in partnership with CMAs through reporting of standardised outputs as per DELWP Output data standards, 2015). The graph highlights the Partnership Statement developed between Gunditj Mirring TOAC and Glenelg Hopkins CMA in 2016. The GHCMA Aboriginal Partnership Framework, developed with Traditional Owner groups, outlines the development of partnership agreements with each group in the region over the next four years. As the strategy progresses, it is envisaged that ICM partnerships outside CMA initiatives will be recorded and promoted.

Major threats and drivers of change

The social and economic future of the region is directly linked to the health and maintenance of the region’s natural resources. Eighty-one per cent of the Glenelg Hopkins region is used for agricultural production, which relies on the ecosystem services provided by a healthy environment. The region is ranked first among Victorian NRM regions by gross value of agricultural commodities. Tourism is based on the region’s natural and cultural values, including recreational use of waterways, national parks and coastal zones. Supporting individual connections to the environment through access to green and blue spaces is also central to community health and well-being11.

Sustaining a healthy and resilient region requires an understanding of the way community and visitors use and interact with the environment, and subsequent adaptation of ICM engagement approaches. For example, regional partnerships that combine socio-economic, cultural and environmental outcomes need to be pursued. This includes recognising diverse opinions on historical and new land use changes and practices across the region, as well as optimising opportunities for cross-tenure and cross-sector collaborations.

Influences on the region’s community are wide ranging and span from global forces, such as climate change and market trends, to local issues, such as access to services and connectivity. Although global forces are largely out of the regional community’s control, they impact the ability to plan and manage local natural resources.

Climate change

Adaptation to the changing climate is already happening on many levels. Throughout 2020, the Department of Environment Water Land and Planning facilitated climate adaptation workshops to support the development of localised adaptation plans and to develop the capacity of regional community and organisational leaders to act as Climate Adaptation Champions. These workshops consistently identified the following region-wide priorities for community and capacity building:

- Improved resilience of communities.

- Embedding the latest climate data and science in decision-making.

- Education and information provision to local communities to help understand economic and social impacts.

- Health agencies to recognise climate adaptation as core business.

The World Health Organization has described climate change as the defining issue for public health in the 21st century. It is an urgent challenge, with implications at global, national, state and community levels. Future projections for the region indicate that drought risk will increase. Hotter and drier conditions can be expected. Temperatures are predicted to increase in all seasons with more hot days and fewer very cold days overall, up to 38% less rainfall, 21% higher mean temperatures and more extreme weather events by 207012.

Rural communities are identified as vulnerable to climate change with environmental, economic and social changes predicted to affect their health13. Of significant concern for the region is the potential for increasing drought conditions to exacerbate mental health problems and increase suicide rates, particularly among male farmers14.

Local angling club representatives the at Red Gum Shield

South West Holistic Farmers field day

Policy and legislation

Political change and policy development directly impact integrated catchment management, with issues such as free trade agreements shaping how productive and urban-based landscapes are managed. Policy and legislative drivers can have both positive effects, such as the shift to increase recognition of Traditional Owners, as well as less desirable outcomes, such as increased competition for funding. Additionally, political and policy changes result in funding reallocations and changes in priorities. These, in turn, affect the community’s capacity for action, research and effective planning.

Recognition of Traditional Owners and First Nations peoples in ICM, at both national and state levels, has resulted in meaningful change within the region. Acknowledgement of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), and Traditional Owner and First Nations cultural aspirations is a positive outcome but has led to increased demands on groups and resourcing challenges. The development of frameworks, strategies, plans and agreements including, for example, Water Resource Plans, Victorian Aboriginal Traditional Owner Engagement Strategy, MOUs between Agencies and Traditional Owner Organisations and/or Groups will continue to shape ICM within the region15.

Ageing population

The ageing demographic trend provides both a challenge and an opportunity for environmental volunteering groups, including Landcare. Historically, these groups have been predominantly led and made up of older people who had time to dedicate to group operation and projects. People living in rural and regional Victoria are more likely to be involved in their communities than people in cities and urban areas, but rates of participation still present a challenge. Organisations that depend on volunteers face a challenge in attracting new volunteers and in ensuring that rates of participation are adequate to provide a stable volunteer workforce. According to the ABS (2015), Australia-wide rates of volunteering dropped from 42% of the population aged over 15 years in 2006 to 32% in 2014.

People and communities: the 2014 regional wellbeing survey16 found that 54% of people in rural and regional Victoria were involved in volunteering, and a further 29% had previously volunteered. This is supported by the 2014 Victorian Population Health Survey data, which shows that 45% of people in rural areas volunteer, compared with just 33% of people in major cities17. However, the 2014 Regional Wellbeing Survey also notes concerns “that a high rate of volunteering may be difficult to sustain into the future, particularly in many rural communities that have a rapidly ageing population”18.

Landcare and environmental volunteer groups across the region are reporting a need to engage new, younger volunteers to carry on the work of their founders and new members are expressing a desire for more flexible, family friendly volunteering. Embracing this will require a shift in the way groups engage with volunteers. The COVID-19 experience of 2020-21 may have provided the catalyst to progress this shift and provide more flexible forms of volunteer engagement.

According to Volunteering Australia’s State of volunteering in Australia 201219, Australians are asking for a wider range of ways to volunteer. They want meaningful volunteer roles and greater flexibility in how and when they volunteer. This includes episodic, online and skilled volunteering, and volunteering through the workplace. Harnessing these expectations through technology can increase the extent to which people are prepared to volunteer.

The changing priority for engagement is consistent with the growing community interest and participation in Citizen Science activities, many of which allow people to contribute meaningfully in their own time and in a place of their choice.

Innovation

Agricultural innovation leading to both extensification and intensification of farming are a way to replace labour with financial and knowledge capital20. Developments in technology have been in response to a range of challenges, such as climate change, labour shortages and costs, and increased demand. It is anticipated that there will be contributions from areas including gene technology, electronic measurement systems such as GPS and ‘big data’ as well as emerging technologies21.

The use of digital technology can attract and retain younger generations to live and work in regional Victoria22, in agriculture as well as start-ups and other businesses. Innovation beyond agriculture is likely to influence and shape the community. The increase in use of technology to support remote working arrangements due to COVID-19 will likely continue in some form, which presents opportunities to attract new community members to live within the region.

Casterton Show

Digital Innovation and Smart Farming Festival, 2020

Outcomes and priority management directions

Outcomes and priority management directions have been developed to show what success looks like for integrated catchment management (ICM) across the Glenelg Hopkins region. Below are the 20 year (long-term) outcomes for communities in ICM. Within these are the proposed six-year outcomes and priority management directions to be achieved within the life of this strategy. The priority management directions are identified across the adaptation pathway stages of resilience, transition and transformation (see RCS approach for more information). Lead and key partners invovled in the delivery are also outlined.

By 2042, integrated catchment management (ICM) supports Traditional Owner self-determination

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Owner rights, interests, obligations and access to Country and water, including cultural flows, are acknowledged and protected. | Traditional Owner communities are supported to develop a broad understanding of their rights and obligations to Country and water. Traditional Owner communities have an increased understanding and awareness of cultural flows. | Traditional Owners are supported to build knowledge across agencies, authorities and the general community of their rights, interests, obligations and access to Country and water. Agencies, authorities and the broader community have an increased understanding and awareness of cultural flows. | Traditional Owners lead the integration of their rights, interests and obligations to water and Country in all aspects of ICM. Traditional Owners influence water legislation and policy to support cultural flows. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| Traditional Owner groups are decision makers and provide strategic leadership in ICM. | Traditional Owners are decision makers in regional planning and investment processes. Traditional Owner country plans are developed and implemented. Traditional Owner partnership agreements are developed with agencies and groups. Traditional Owners build familiarity with organisations and agency roles and responsibility in ICM. | Appropriate governance structures across Traditional Owner organisations and other agencies are in place to support Traditional Owner leadership in ICM. Traditional Owners are decision makers in long-term and on-going programs and activities that look after Country, including control of resources. Traditional Owner communities are supported to build knowledge and understanding of cultural landscapes and traditional land management practices, as well as western approaches to ICM. | Traditional Owner communities promote the cultural importance of land and sea country. Aboriginal language and names are incorporated into ICM. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| The social wellbeing of Traditional Owner communities has increased as a result of involvement in ICM. | Traditional Owner community members are supported to connect and spend time on Country, to support cultural identity. | Cultural and social outcomes for Traditional Owners are built into project delivery and outcomes. Traditional Owners living off Country, are supported to engage with Country through digitial innovations. | Aboriginal culture and language are supported and celebrated. Traditional Owner communities enjoy social and emotional wellbeing. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| The economic benefit for Traditional Owner communities has increased as a result of involvement in ICM. | Traditional Owner Groups are supported to employ staff to increase capacity to care for Country. Traditional Owner community members benefit from ICM through opportunities such as employment and training. | Traditional Owner groups are leading strategy development and activities to look after Country, including development of works crews and other opporunities to support economic growth. | Traditional Owner group governance structures support strong workforce participation and achieve wealth equality for their community. Regional agencies are supporting Traditional Owner employment and procurement opportunities. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| There is an increased connection of agencies, authorities and community groups with Traditional Owner communities to build awareness and understanding of cultural landscapes management. | Traditional Owner country plan implementation is supported. Partnership agreements are developed with Traditional Owners. | Activities that support relationship building between Traditional Owners and community, landholders and land managers are implemented, including cultural awareness and competency activities. Community and land manager awareness of cultural heritage protection is supported and enhanced. Knowledge sharing between land managers and Traditional Owners is promoted to build awareness and capacity. | Traditional knowledge and cultural land management practices are incorporated into ICM education materials for land managers and agencies. Education is provided for the broader community, including schools, to promote the rich local cultural heritage of Country. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Local Government, Landcare Groups, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

By 2042, the number of people connected to and involved in integrated catchment management has increased

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The regional community is informed and has capacity to adapt to, and mitigate, the impacts of climate change. | Traditional Owner communities are supported to contribute to planning and action for climate change adaptation, and Traditional Owner rights and obligations are respected during these processes Surveys of community knowledge, understanding and capacity to adapt to and mitigate climate change. Regional information is provided to build community awareness and understanding of the impacts of climate change on peoples social, cultural and economic well-being, as well as environmental health. | Education and capacity building opportunities are provided for different stakeholder groups around adaption, mitigation, resilience, and disaster preparedness and recovery related to climate change. | Climate change adaptation and disaster preparedness is driven through community action and the development of relevant regional and local plans. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | DELWP, Local Government, Southwest Primary Care Partnership |

| The regional community is more engaged and empowered to participate and partner in integrated catchment management. | Conduct survey to establish baseline information on the community's current level of engagement and empowerment to participate and partner in integrated catchment management. Land stewardship is supported by landholders, Landcare and other community groups through the delivery of ICM. activities Social media and other technologies are embraced to promote ICM, engagement events and activities. Community are involved in regional ICM planning and decision making, including capacity building and knowledge sharing opportunities. | Landcare and other community groups are supported to build the capacity of their volunteer base, including training and development of information toolkits. Regional and cross-sectoral partnerships are developed and maintained to enhance ICM planning, investment and delivery. Joint promotional campaigns, including sharing and celebrating ICM successes, are implemented across the region. Citizen science and environmental volunteering opportunities are developed and promoted through targeted communication campaigns to enable more active participation in ICM. | Pathways to support broader community and youth engagement in ICM are developed. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Traditional Owner Organisations, DELWP, Local Government, Parks Victoria, Southwest Primary Care Partnership, Nature Glenelg Trust, recreational fishing groups, Landcare and community based NRM groups |

| The regional community recognises that the social, cultural and economic benefits of people connecting with nature depends on a healthy environment.* | Conduct survey to establish baseline information on the community's recognition that social, cultural and economic benefits of connecting with nature depend on a healthy environment. Community and recreational events and activities that connect people with nature are supported e.g. art-based activities and recreational fishing. The health of existing green-blue spaces and other open spaces are maintained to support community use and benefits. Appropriate recreational infrastructure is supported to connect people to the environment. | The social connections that come from participation in Landcare and other community group activities are better understood and promoted. The regions natural environment and Aboriginal cultural values are promoted through targeted tourism campaigns. Research into the economic value of community participation in ICM activities and programs is supported. Pro-environmental behaviours such as spending time in nature, volunteering for nature, being a champion for nature, planting native plants and keeping domestic animals contained or on a leash in natural areas are promoted. | The health and well-being benefits of experiencing nature and participating in ICM are researched and communicated in partnership with health providers. Green-blue urban areas and open spaces, including walking and rail trails, are designed and successfully incorporated to support community health and well-being. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Traditional Owner Organisations, DELWP, Local Government, Parks Victoria, Southwest Primary Care Partnership, Nature Glenelg Trust, recreational fishing groups, Landcare and community based NRM groups |

*Outcome is linked to the Biodiversity 2037 goal that ‘Victorians value nature’ and that Victorians understand that their personal wellbeing and the economic wellbeing of the state are dependent on the health of the natural environment.

Key strategies and plans that relate to the delivery of community outcomes include:

- Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037

- Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2019-2030

- Water for Victoria

- Our Catchments Our Communities

- Victorians Volunteering for Nature – Environmental Volunteering Plan

- Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2018-2023

- Pupangarli Marnmarnepu ‘Owning Our Future’ Aboriginal Self-Determination Reform Strategy 2020-2025

- Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Landscapes Strategy

- Growing What is Good Country Plan, Voices of the Wotjobaluk Nations

- Meerreengeeye ngakeepoorryeeyt, Eastern Maar Country Plan

- Ngootyong Gunditj Ngootyong Mara South West Management Plan

- Paleert Tjaara Dja, Let’s make Country good together 2020-2030, Wadawurrung Country Plan

- Glenelg Hopkins Climate Change Strategy

- Glenelg Hopkins CMA Partnership and Engagement Strategy

- Warrnambool 2040

- Glenelg Shire 2040, Our Future Together

- Moyne 2040