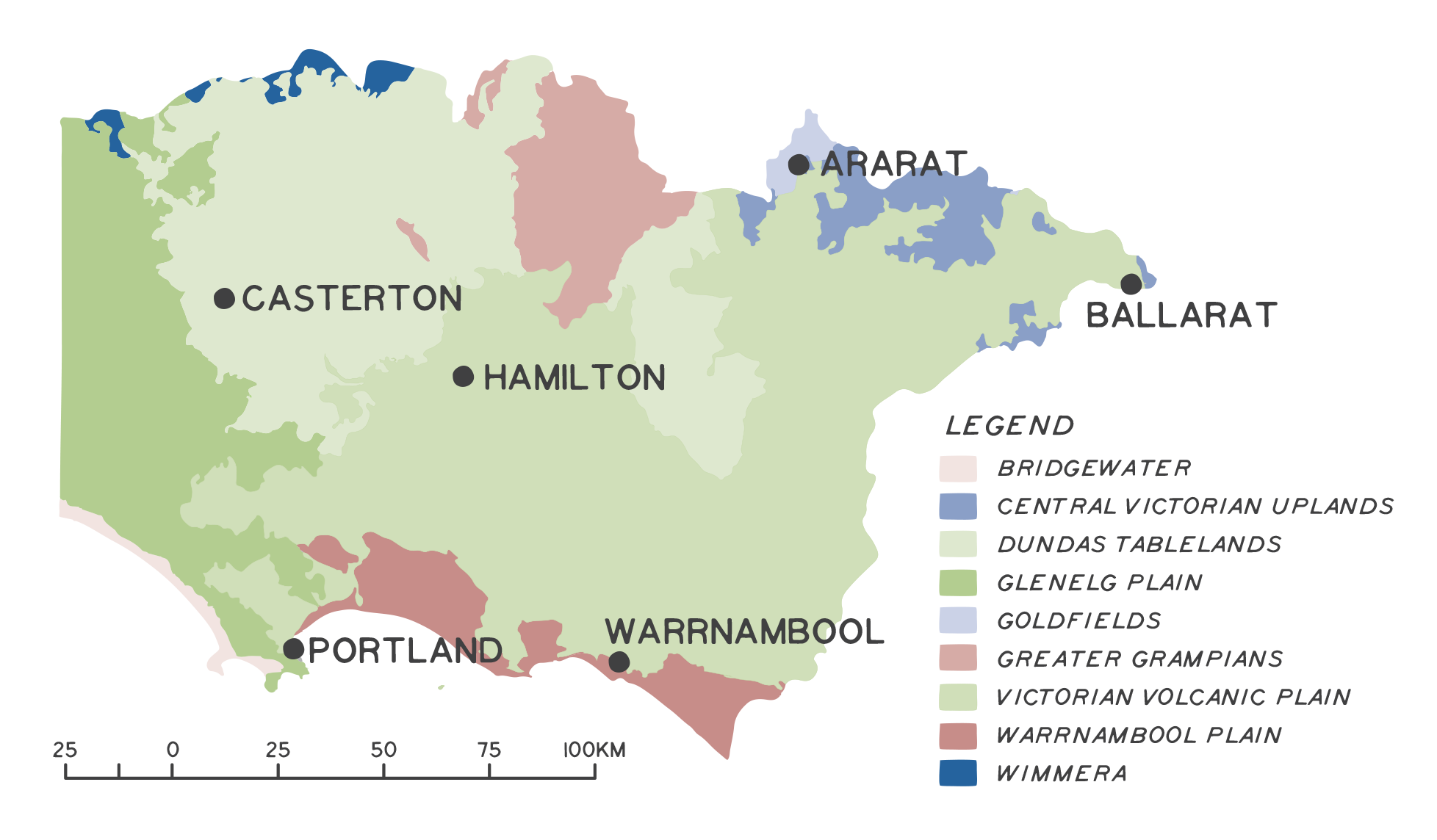

The Glenelg Hopkins region is a diverse landscape ranging from ancient sandstone and granite mountains to expansive grassy plains, woodlands and forests, and a coastline of exposed cliffs and sandy beaches. This landscape has been divided into nine bioregions, which are defined as broad areas of land sharing similar ecological processes owing to their shared geological histories. These bioregions have been further shaped through human occupation in the region over at least the past 27,000 years, with many ecosystems having evolved a dependency on Aboriginal people’s land use to maintain diversity1.

Collectively, these areas provide habitat for a recorded 1,391 native plant species and 483 native animal species across the region (although some animal groups are substantially underrepresented in records e.g. invertebrates). Nationally significant bioregions captured within the Glenelg Hopkins region include 69% of the Greater Grampians and 53% of the Victorian Volcanic Plain (VVP). The VVP, and areas of Bridgewater and the Glenelg Plain, make up two of Australia’s 15 biodiversity hotspots, and the only nationally recognised biodiversity hotspots in Victoria. Explore each of the Glenelg Hopkins bioregions in more detail below by clicking on the map.

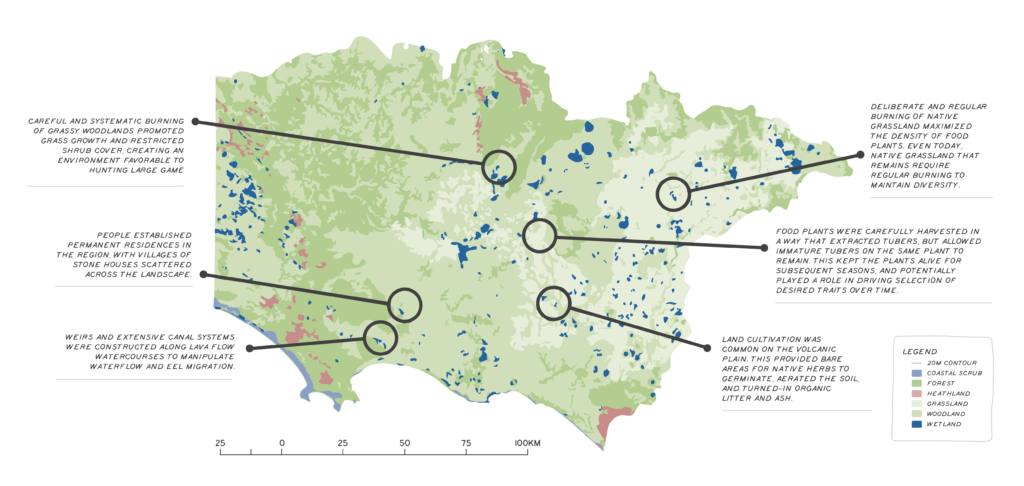

Aboriginal land management as a driver of biodiversity patterns

Aboriginal people have lived in the Glenelg Hopkins region for at least 27,000 years. Over this period, Aboriginal land use has played a role in shaping the region’s biodiversity. Declines in the condition of ecosystems across the region have in part occurred through the decline of important cultural land use practices, including the use of fire. Below are some of the many ways Aboriginal people have shaped the region’s biodiversity.

Bulbine lily

Blue grass lily

Chocolate lily

Murnong

Murnong tuber

Water ribbon

Photos: some traditional food and medicinal plants found across the region

Wadawurrung Country

“Our inland country includes western volcanic plains and grasslands, with their temperate grasslands and grassy eucalypt woodlands once had enough food and resources for us to live here permanently all year in our stone huts as a community in family groups. The grasslands were full of food grasses, and our women harvested roots and tubers, like murrnong and bulbine lily with their digging sticks. Our Country is home to many different types of snakes, lizards, frogs, moths, birds and mammals. Kwenda (Bandicoot) or Yoorn (spotted tail quoll) was once here as was the eastern barred bandicoot who helped our women in digging and tilling the soil to increase the growth of murnong, helping our women to till the soil but now are extinct or rarely seen in this landscape.

Fire and cultural burning in this Country was and continues to be important for renewing growth, food for animals and people. The remnants of farming terraces near Little River are a further reminder that our people were farming and managing this country, well before Europeans and sheep took over our lands. Now the Victorian Volcanic Grasslands are one of the most threatened ecological communities with less than 5% left as it turned into farming and housing estates.”

From Paleert Tjaara Dja – let’s make Country good together 2020-2030 – Wadawurrung Country Plan

Wadawurrung cultural burn, native grasslands at Worram (Skipton)

Assessment of current condition and trends

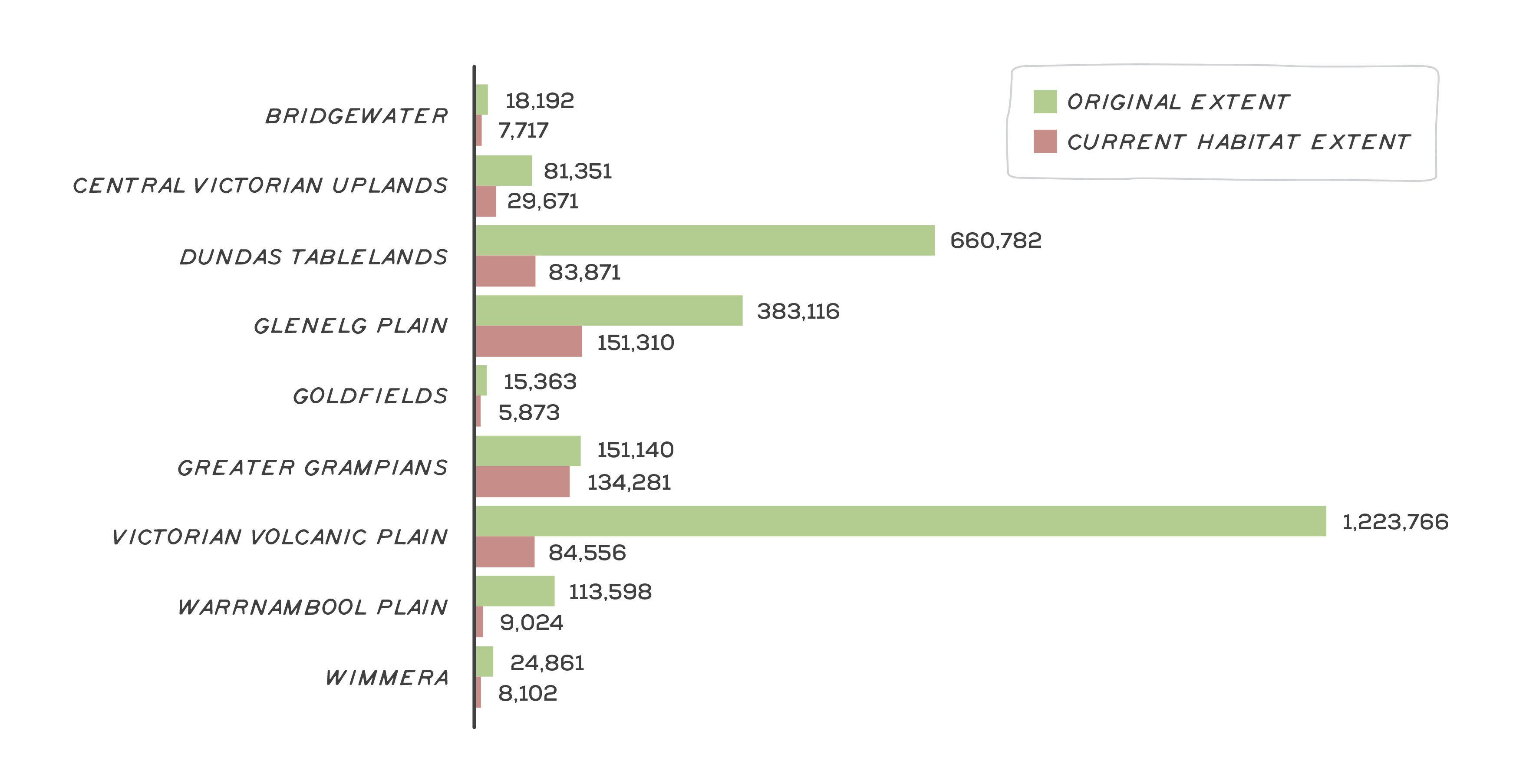

The Glenelg Hopkins region has undergone extensive land clearing since European arrival, with 81% of native vegetation cover now cleared. Historical land clearing has not been evenly distributed across the region. For example, while the Greater Grampians has retained 89% native vegetation cover, the catchment’s largest bioregion, the VVP, has retained just 7% (Figure 1).

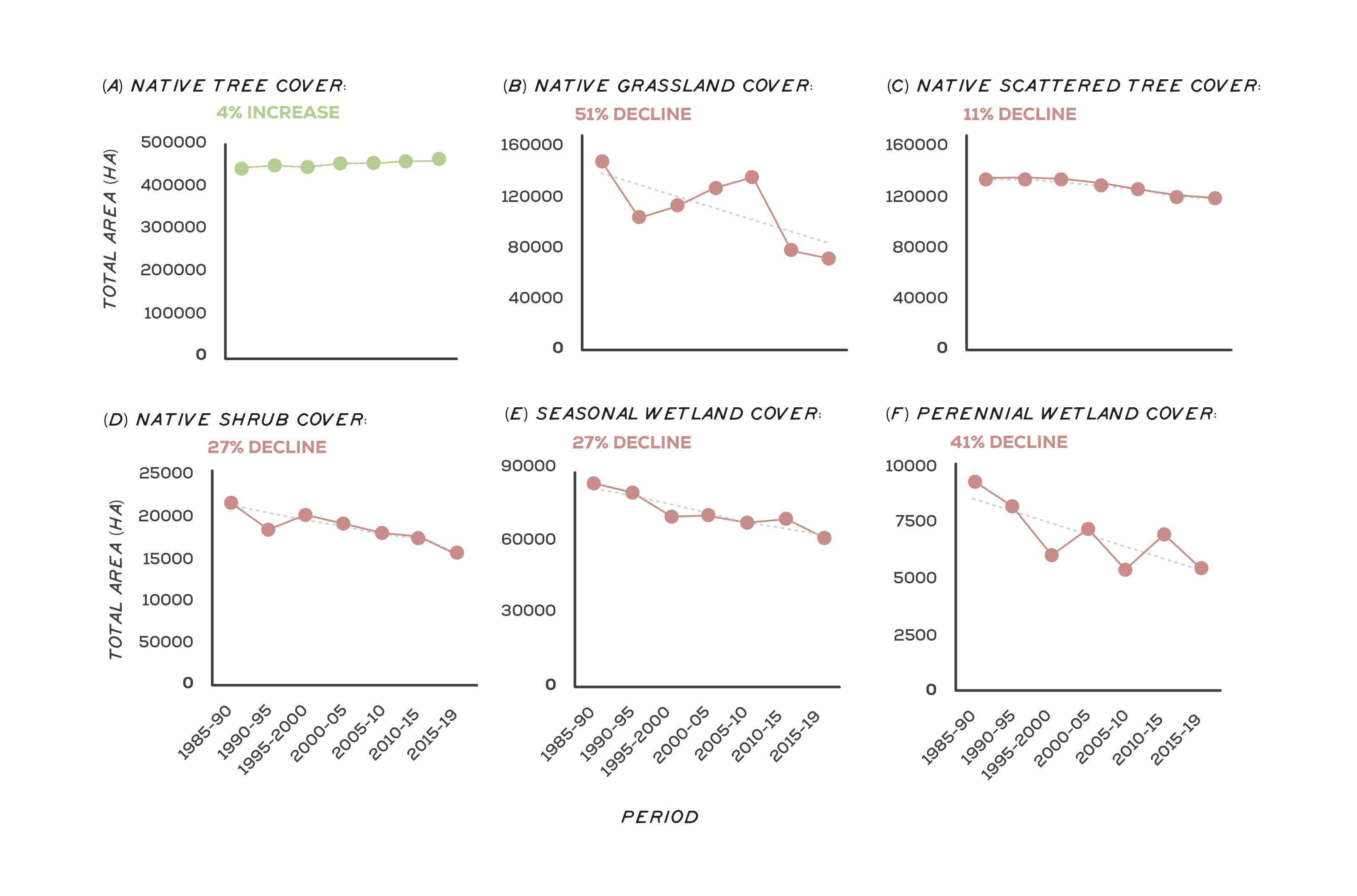

Despite having undergone extensive habitat loss, the VVP provides habitat for a disproportionally high amount of the region’s biodiversity. More native species have been recorded on VVP than any other Glenelg Hopkins bioregion, despite other bioregions such as the Greater Grampians and Glenelg Plain having retained much larger amounts of total native vegetation cover. The most heavily cleared of the VVP ecological communities have been the natural temperate grassland and grassy eucalypt woodland, both of which are listed as Critically Endangered under the Commonwealth EPBC Act. It is estimated that less than 1% of these communities remain in Victoria, and a further 47% of remaining native grassland has been lost in the region since 2010. High-quality native grassland is largely restricted to regularly burnt roadsides and small patches on farms2. Despite being small and fragmented, research has shown that under appropriate fire management, VVP grassland remnants are highly resilient and diverse3. In the Glenelg Hopkins region, roadside grassland that have long received frequent burning have undergone minimal floristic change since the late 1980s4. Figure 2 and the video below show the change in dominant native vegetation in the region over time.

The loss of seasonal herbaceous wetlands is accelerating (Figure 2). These wetlands occur largely on private land across the VVP, the Glenelg Plain and the Dundas Tablelands, and are listed as a critically endangered ecological community under the Commonwealth EPBC Act. Seasonal herbaceous wetlands are defined as wetlands rich in native grasses and herbs that hold water over the wet months of the year, before drying out over summer. They are generally highly diverse with minimal non-native plant cover where the installation of drains and cropping has been avoided5. However, over the past 30 years, native vegetation cover in seasonal wetlands has declined by 27% (Figure 2e), and between 2010 and 2016, there was a 40% increase in cropping of these wetlands in a large cluster south-east of the Grampians6. As broadacre cropping replaces traditional grazing practices in parts of the catchment, combined with a drying landscape through climate change, the loss of these wetlands is likely to continue7.

Red gum woodlands have long dominated large areas of the Glenelg Hopkins region, particularly across the Dundas Tablelands and parts of the Glenelg Plain and VVP. The understory of these woodlands was largely cleared in the 1950s, with remaining high-quality sites typically less than 10 ha and under threat from weed invasion and declining fire frequency8. In areas of extensive pasture establishment, large red gum trees have often been retained, providing essential habitat for many hollow-dependent species (e.g. south-eastern red-tailed black cockatoo). These trees are now in decline. The number of red gum paddock trees dropped by 35% in parts of the Glenelg Hopkins region between 2003 and 2013, with climate change considered a contributing factor9. In addition, the total cover of scattered native paddock trees across the region has declined by 11% since 1990 (Figure 2c). Through ongoing grazing and land cultivation, red gum recruitment has become largely restricted to roadsides10. Given these trees can live for centuries, the difference between the initial and final levels of tree loss caused by European arrival will take many more decades, if not centuries to play-out. A trend in the opposite direction has been the revegetation of woody plants across the region, particularly along watercourses, as part of riparian protection works. These plantations provide valuable habitat for birds, particularly in heavily cleared landscapes11.

Red gum paddock trees

Photo: Southern Grampians Shire

Critically endangered seasonal herbaceous wetlands

Major threats and drivers of change

Land clearing

Land clearing continues to be a major threat to biodiversity in the Glenelg Hopkins region and is a major cause of biodiversity losses globally12. The Commonwealth EPBC Act provides legislative protection to some of the most endangered ecological communities, i.e. grassy eucalypt woodland and natural temperate grassland of the VVP, and seasonal herbaceous wetlands. However, landholders are often unaware of these protections, find information difficult to locate or lack clarity on how these laws impact on farming practices13. Incentive-based programs that target native vegetation protection on private land provide vital opportunities to engage with the community and communicate the importance of protecting native vegetation. However, communicating the legislative protections remains challenging14. Research has demonstrated that coupled with any enforcement of land clearing regulations, message framing is important, as is strengthening relationships between landholders and extension officers, and where possible, disseminating information through local champions15.

Fire

Native grassland on the roadsides of the VVP and Dundas Tablelands are among the most biodiverse ecological communities in the Glenelg Hopkins region. This ecological community relies on frequent fire to maintain diversity, which has been occurring systematically through community and CFA hazard reduction burns since at least the 1930s16. Regular burning is also likely to have been how Aboriginal people managed the plains prior to European arrival17. Without fire, diversity in these grasslands can be permanently lost within a decade18. Roadside burning is undertaken by local CFA fire brigade volunteers. These volunteers say there are challenges in maintaining the burns as a result of changes in social demographics, land uses and regulatory processes19. As a result, the extent of roadside burning is in decline, which will have a major negative impact on the region’s biodiversity through the loss of high-quality roadside native grassland20.

The highest-quality native grassland in the Glenelg Hopkins region are found on the roadsides of the VVP and Dundas Tablelands. Roadside burning by local CFA brigades is key to maintaining the biodiversity in these ecosystems.

Native grassland across the Victorian Volcanic Plains

Climate change

Climate change is likely to be a significant driver of biodiversity change. Many species may need to shift their distribution as they are pushed to the edge of their climatic tolerance, which will be challenging in fragmented landscapes and for species with limited capacity to disperse (e.g. native herbaceous plants). Habitat corridors in areas that facilitate movement across climatic gradients, as well as direct translocation of species and gene mixing may therefore be required21. Acting before projected changes occur will be critical22. For species with specific soil tolerances this may not be possible as suitable habitats may no longer exist. Under a scenario of a drying landscape, aquatic, semi-aquatic and riparian species will be restricted to increasingly small portions of the landscape. This, in turn, interacts with land-use to trigger cascading impacts. For example, under a drying climate there is a perceived opportunity to crop seasonal wetlands, pushing these critically endangered ecosystems further towards extinction23.

For native grasslands, elevated temperature and carbon dioxide may intensify competition through increases in biomass production of native kangaroo grass, while reducing growth of co-occurring species24. It may be possible to mediate these changes through an appropriate disturbance regime25. Plant recruitment may be resilient to changes in the amount of annual rainfall, but sensitive to increases in temperature and changes in rainfall seasonality26. For woodlands and forests, periods of prolonged drought are likely to cause significant tree die-back, potentially leading to permanent changes in species composition across landscapes and create opportunities for non-native species to become established27.

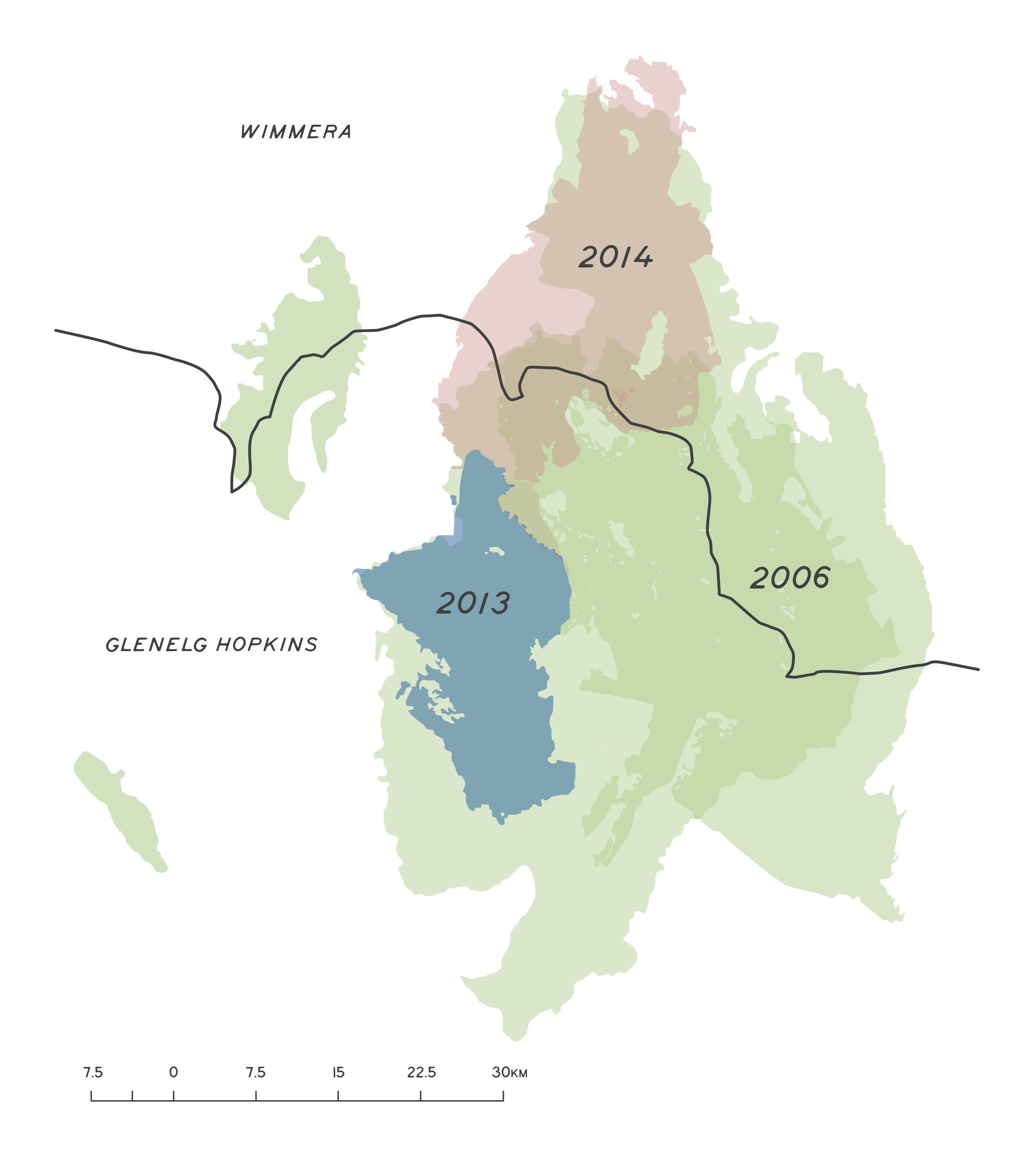

Extreme climatic events and large wildfires are predicted to increase and the intervals between successive fires to decrease28. This has become evident in Gariwerd (Grampians National Park), where a combined 186,800 ha burnt in the wildfires of 2006, 2013 and 2014 (Figure 3)29. These were three of the largest bushfires ever recorded in the Grampians, resulting in 90% of the park burning. In response, population numbers of small mammals have dramatically declined30. These include the southern brown bandicoot, heath mouse, common dunnart and several species of antechinus. There is now very little of the long-unburnt vegetation that these small mammal populations require to thrive31.

Current fire prevention strategies across the Glenelg Hopkins region are primarily focused on hazard reduction burns during autumn and spring. However, there are limitations in what these burns can achieve under increasingly frequent extreme weather conditions32. Other potential actions could include establishing green fire breaks and linear plantations of low-flammable vegetation across the landscape that may potentially slow fire spread, and greater efficiency in detecting wildfire ignition to reduce first attack response times33. Most actions will be deployed with imperfect knowledge, therefore rigorous monitoring is essential to facilitate effective adaptive management34.

Pest plants and animals, grazing and pathogens

Habitat condition across the Glenelg Hopkins region is declining in response to various drivers, such as weed invasion, stock and pest grazing, and pathogens. Over-browsing by native herbivores has been linked to declines in habitat condition. For example, over-grazing of manna gums by koalas is a major regional issue across the Budj Bim cultural landscape. However, in some instances, a decline in heavy kangaroo grazing may have had a negative impact on native vegetation (e.g. native annual plants in grassy woodlands)35. While stock grazing of native vegetation has generally negative impacts on biodiversity (e.g. selective/over-grazing, soil disturbance), in some instances periodic crash grazing of grassy ecosystems can be used beneficially as an alternative to burning. Although this is a sub-optimal form of management compared to burning and not all species are likely to persist. However, if timed appropriately, it can prevent the ecosystem from being permanently lost. This form of management is best suited to long-grazed grassland on farms rather than roadside native grasslands.

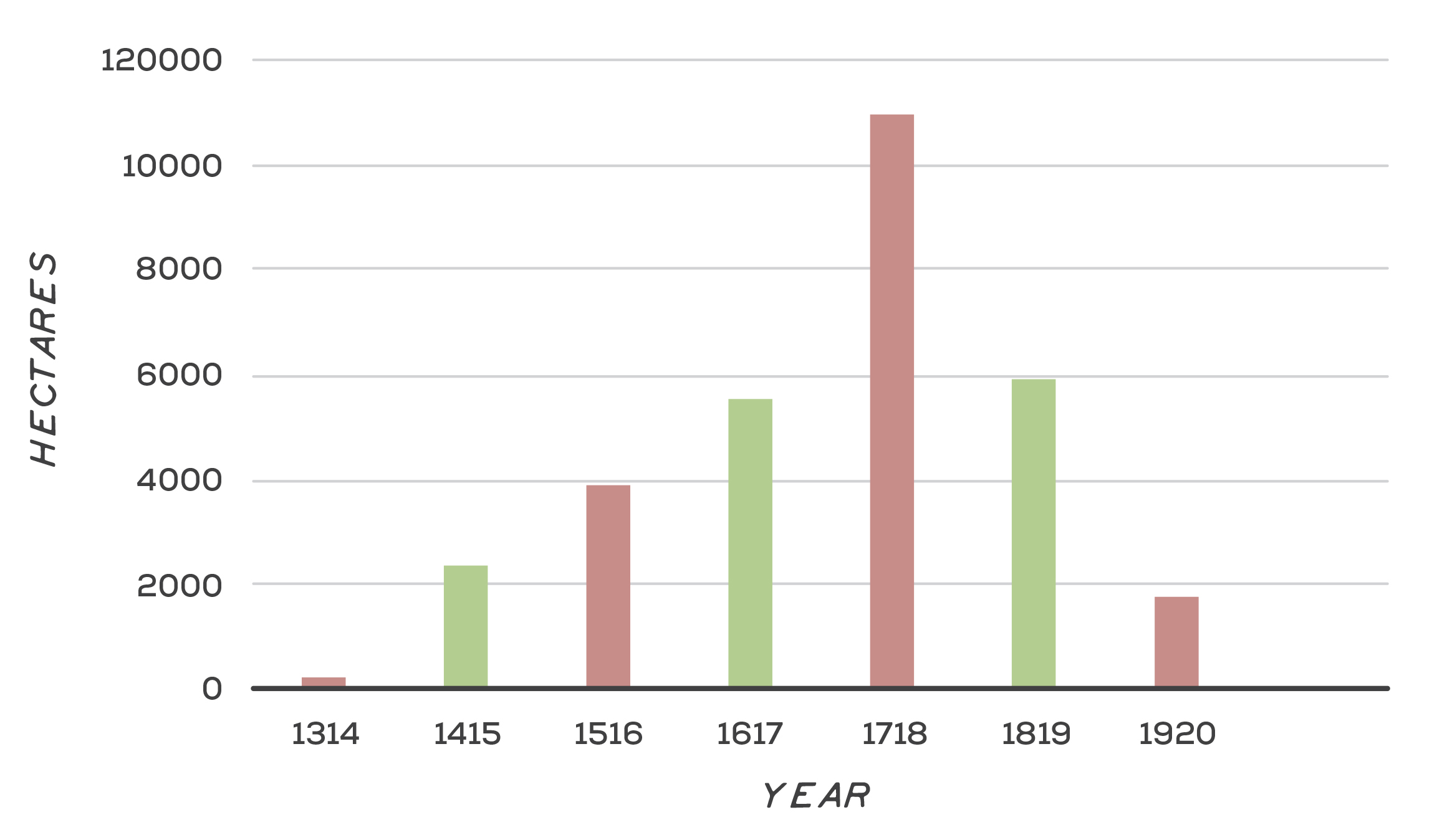

Grassy ecosystems of the region have so far avoided significant invasion from the aggressive Nassella grasses common closer to Melbourne (e.g. Chilean needle-grass and serrated tussock, although the risk may increase with climate change), however they do face a threat from introduced pasture grasses. One of the most concerning species is Phalaris, which can rapidly out-compete native species and alter fire behaviour. For example, Phalaris-dominated roadsides accumulate higher levels of biomass, burn three times as intense and are far more unpredictable than fire on native-dominated roadsides36. In areas such as the Glenelg Plain and Dundas Tablelands, woody species such as pine, coast wattle and hedge wattle commonly invade forests and woodlands, developing dense canopies that can inhibit the recruitment of native plants. This process has also been occurring in the Grampians within the Victoria Valley, where manuka has invaded red gum woodland, possibly in response to a decline in fire frequency and the legacy of historical grazing37. Figure 4 shows the area of weed control works in the Glenelg Hopkins region since 2013. This data set is from internal tracking of outputs or activities that are delivered by or in partnership with CMAs through reporting of standardised outputs as per DELWP Output data standards, 2015.

Outcomes and priority management directions

Outcomes and priority management directions have been developed to show what success looks like for integrated catchment management (ICM) across the Glenelg Hopkins region. Below are the 20 year (long-term) outcomes for habitat and native vegetation. Within these are the proposed six-year outcomes and priority management directions to be achieved within the life of this strategy. The priority management directions are identified across the adaptation pathway stages of resilience, transition and transformation (see RCS approach for more information). Lead and key partners involved in delivery are also outlined.

By 2042, the extent of native vegetation will be maintained or increased

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The extent of revegetation has increased across the region, including at least 10,000 ha in priority locations for habitat connectivity.* | Work with landholders to support revegetation that delivers multiple benefits for biodiversity and productivity (e.g. improve connectivity, buffer native vegetation, provide wind breaks, stabilise erosion). Revegetation to improve connectivity will be focused at priority locations consistent with Strategic Management Prospects, Biodiversity Response Planning and other science based decision support tools wherever possible. Consider future climate when selecting species and provenance of seed , to build resilience into plantings. | Establish sustainable sources of seed to meet revegetation targets (i.e. Seed Production Areas), including a focus on species not widely available from commercial nurseries. | Prioritise connectivity projects that have the potential to facilitate species movement in response to climate change. | DELWP, Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Local Government, Greening Australia, Traditional Owner Organisations, Trust for Nature, Landcare and community based NRM groups |

| The community has increased knowledge and capacity to support remnant vegetation protection. | Provide incentives and technical support to increase the effective stewardship of native vegetation. Establish management agreements with private landholders to protect and manage native vegetation (e.g. stewardship and tender programs, riparian management licences). Support landholder engagement and education about remnant vegetation values and legal protections. | Identify areas and ecological communities that are at increased risk from land clearing, climate change and land use change (including communities like grasslands or wetlands which may be poorly recognised). Support increased compliance measures by relevant authorities to reduce intentional and uninformed clearance of habitats. | Develop improved and better informed planning controls and updated legislation to support protection and reduce clearance of all remnant habitats. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | DELWP, Local Government, Landcare and community based NRM groups |

*Outcome is linked to the statewide Biodiversity 2037 target, ‘200,000 hectares of revegetation in priority locations for habitat connectivity since 2017’. In the Glenelg Hopkins region the 2037 the target is ‘20,000 hectares of revegetation in priority locations for habitat connectivity since 2017’.

By 2042, the condition, function and resilience of native ecosystems will be maintained or improved

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Owner communities have the capacity, knowledge and authority to look after their understanding of native habitats, including culturally significant species, and groundwater dependant systems. | Traditional Owner groups are supported to research and understand the management of cultural landscapes, including totemic species. Traditional Owners are supported to undertake cultural burning practices. | Seasonal calendars are developed using traditional ecological knowledge and cultural practices. Cultural plant species are mapped, propagated and planted. Cultural plant species are used in revegetation projects across the region. Knowledge around cultural plant species is shared and communicated with broader community where appropriate. | Traditional Owner Groups are leading cultural landscape management. Seasonal Calendars guide how Country is monitored and looked after. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| 7,500 ha of native vegetation will be permanently protected by inclusion in the protected areas network.* | Implement education programs to encourage the uptake of permanent protection options. Improve understanding and recognition of the values of remnant vegetation in the landscape. Provide incentives for permanent protection and on-going management. Provide technical advice, funding and other requirements to support on-going stewardship of permanently protected sites. | Investigate and actively promote the economic values associated with permanently protected remnant vegetation (including carbon credits, offsets for development and direct ecosystem services). Adapt conservation covenants/permanent protection options to allow landholders to maximise their ability to access funds to continue to manage covenants (e.g. offsets carbon credits). | Develop a comprehensive and flexible suite of permanent protection options that can be tailored to a greater range of circumstance and values (e.g. biodiversity values in the agricultural landscape, carbon sequestration, wetland protection, cultural values, genetic flow). | Trust for Nature | DELWP, Landcare and community based NRM groups, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| 72,000 ha under sustained weed control and 184,000 ha under sustained herbivore control in priority locations.# | Prioritise sustained control of weeds and herbivores across priority locations to maximise benefits to habitat and species. | Identify emerging, high risk pest plant and animal species including those that have the potential to become high-threat with future climate change. Develop education, enforcement and detection methods to reduce risk of emerging high risk pest plants and animals. | Investigate appropriate biocontrols and the development of new control methods and technologies to achieve effective landscape scale control. | DELWP | Parks Victoria, Traditional Owner Organisations, Local Government, Agriculture Victoria, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| The ecological processes that underpin the function and resilience of native vegetation are better understood and built into restoration and conservation programs. | Implement ecological burning regimes targeted to maximise the ecological requirements of the ecological community. Restore functional hydrology, including hydrological connectivity, to waterways to support a range of terrestrial and aquatic species/communities. | Manage threats to ecosystem function in partnership with relevant organisations (e.g. with Traditional Owners, landholders, fire authorities, and government agencies). Continue to refine understanding of the ecological responses to cultural burning and hydrological restoration. | Support research and the adoption of new and innovative approaches to managing threats and improving ecosystem resilience. Undertake research to model changes to ecosystem persistence and extent under climate change and use to identify opportunities for future ecological transition planning. | DELWP, Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Traditional Owner Organisations, Local Government, CFA, Trust for Nature, Greening Australia |

| The connectivity of habitat for species, populations, and communities will be improved | Protect and restore paddock trees and their role in maintaining regional biodiversity (mitigating threats to health, protecting standing dead trees, revegetation to buffer and maximise replacement and biodiversity benefits). Restore riparian connectivity through revegetation and stock exclusion along rivers and support wetland restoration that improves the movement of species. Revegetate to create appropriate links between remnant habitats. Establish baseline of connectivity for priority landscapes. | Enhance resilience to climate change by increasing connectivity to facilitate species dispersal, consistent with SMP priority locations and considerations of species dispersal modes, and future climate projections. Investigate local changes in habitat condition and function and the impacts to key species. | Facilitate species movement in response to climate change informed by species dispersal modes and landscape barriers. Complete a pilot project to establish a habitat corridor that facilitates species movement across a climatic gradient in partnership with stakeholders. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | DELWP, Landcare and community based NRM groups, Universities, Local Government |

| The resilience and condition of protected areas and public land will be maintained or improved | Manage threats to the function and resilience of protected areas and protect economic, cultural and social values. Support Traditional Owners in managing biodiversity and cultural values. Improve the condition of significant assets including Ramsar sites, National Parks, World Heritage values and key habitats. Provide incentives and technical support to increase the effective stewardship of native vegetation. | Support the aspirations of Traditional Owners in managing Indigenous Protected Areas and the protection of their intellectual property. Including assistance with biodiversity management, economic development and adapting to climate change. | Develop a strategy for managing listed ecological communities along roadsides - the strategy will clearly articulate the roles various stakeholders play in roadside vegetation management, identify risks within the stakeholder groups, and ensure the long-term management of roadside vegetation is sustainable. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation, Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation, Parks Victoria. Additional partners TBD. | Trust for Nature, Local Government, Department of Transport, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

*Outcome is linked to the statewide Biodiversity 2037 target, ‘200,000 hectares permanently protected since 2017’. In the Glenelg Hopkins region the 2037 target is ‘15,000 hectares permanently protected since 2017’.

#Outcome is linked to the statewide Biodiversity 2037 targets, ‘1,500,000 hectares in priority locations under sustained weed control’ and ‘4,000,000 hectares in priority locations under sustained herbivore control’. In the Glenelg Hopkins region the 2037 targets are, ‘90,000 hectares in priority locations under sustained weed control’ and ‘230,000 hectares in priority locations under sustained herbivore control’.

Key strategies and plans that relate to the delivery of native habitat and vegetation outcomes include:

- Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037

- Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2019-2030

- Australian Government Threatened Species Strategy 2021-2031

- Australia’s Native Vegetation Framework

- Growing What is Good Country Plan, Voices of the Wotjobaluk Nations

- Meerreengeeye ngakeepoorryeeyt, Eastern Maar Country Plan

- Ngootyong Gunditj Ngootyong Mara South West Management Plan

- Paleert Tjaara Dja, Let’s make Country good together 2020-2030, Wadawurrung Country Plan

A range of science based decision support tools are available to support the identification of priorities and management approaches to deliver outcomes for regional species and ecological communities across the landscape.

- Biodiversity Response Planning

- Strategic Management Prospects,

- Threatened Species Framework,

- Specific Needs Analysis

- Biodiversity 2037 Knowledge Framework which helps to identify knowledge gaps.

Climate change adaptation and planning is a core principle underlying the biodiversity outcomes of the RCS and is reflected in the identification of management priorities ranging from resilience to transition to transformation priorities. The following strategic documents provide guidance on climate change adaptation planning for biodiversity in the region, more information on the Climate Change page.

- Glenelg Hopkins Climate Change Strategy

- Natural Environment Climate Change Adaptation Action Plan 2022-2026