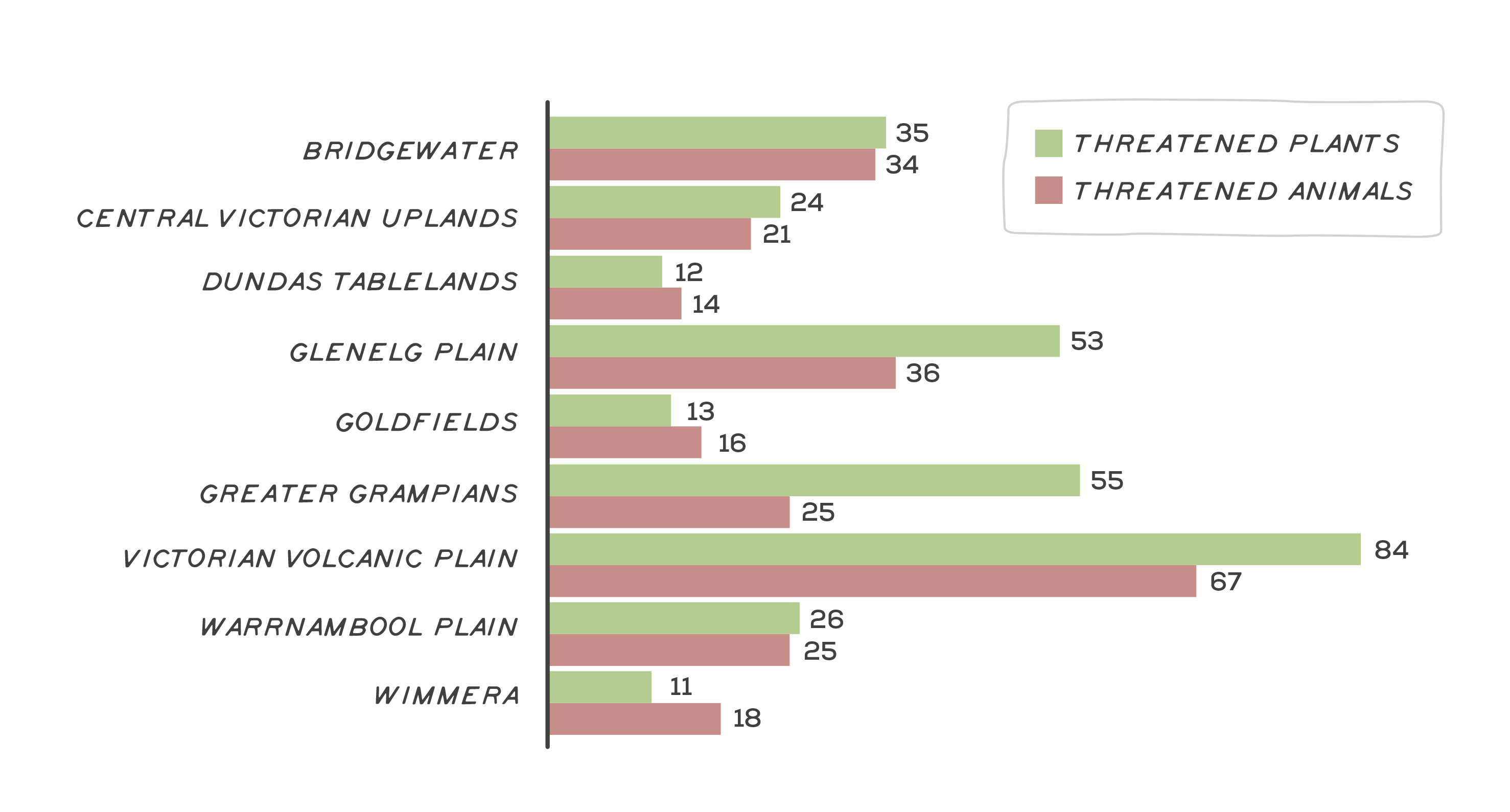

Victoria is experiencing a period of rapid species decline1. Within the Glenelg Hopkins region, 295 native species are considered to be threatened with extinction. Of these, 103 are animals and 192 plants.

Landscapes that undergo significant habitat loss are expected to experience large rates of species loss2. In landscapes that have undergone relatively recent losses of habitat, such as the Glenelg Hopkins region (81% habitat loss since the 1830s), the difference between initial and final levels of extinction may take many more decades to be realised3. Scientists call this concept of future species extinctions caused by habitat loss in the past ‘extinction debt’4. Because there are time delays in the impact habitat loss has on species, it is likely that without significant intervention, many more species will be lost from the Glenelg Hopkins region.

Threatened species are categorised according to their likelihood of extinction in the ‘near future’, with their threat status elevated as the likelihood of extinction increases and the need for intervention becomes more pressing. The most threatened category is ‘Critically Endangered’ followed by ‘Endangered’ and ‘Vulnerable’. Conservation actions implemented to prevent extinction are informed through Recovery Plans (for species that are listed as threatened nationally) and Action Statements (for species listed as threatened in Victoria under the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1998 (FFG Act)). These documents are a vital resource written by scientific experts, identifying both threats and the actions most likely to prevent further decline.

Many threatened species share habitat and common threats. It is likely that specific actions will benefit a broad range of threatened and declining species. Decision support tools such as Strategic Management Prospects, specific needs analysis, recovery plans and conservation advices can assist in identifying the priority actions to benefit species and their habitats.

The most frequently identified threats for the region’s native species are outlined in ‘Major threats and drivers of change’.

Learn more about some of the region’s threatened species by clicking on the photos below.

Assessment of current condition and trends

Twenty-one per cent of native species in the Glenelg Hopkins region are threatened with extinction. This includes 14% of recorded native plants and 22% of recorded native animals (Figure 1). The number of threatened species tends to be highest in the most heavily cleared parts of the landscape. For example, the VVP is the most heavily cleared bioregion in the Glenelg Hopkins catchment and harbours the highest number of threatened species.

Across the region there are 100 critically endangered species, 141 endangered species and 54 vulnerable species, including:

- 31 critically endangered animal species, including the southern bent-wing bat, the southern right whale and the orange-bellied parrot5.

- 69 critically endangered plant species, including the nationally listed spiny rice-flower6 and coast helmet-orchid.

Species closest to extinction are those that are considered critically endangered, followed by endangered and vulnerable. A list of all threatened species in the region can be found below:

Major threats and drivers of change

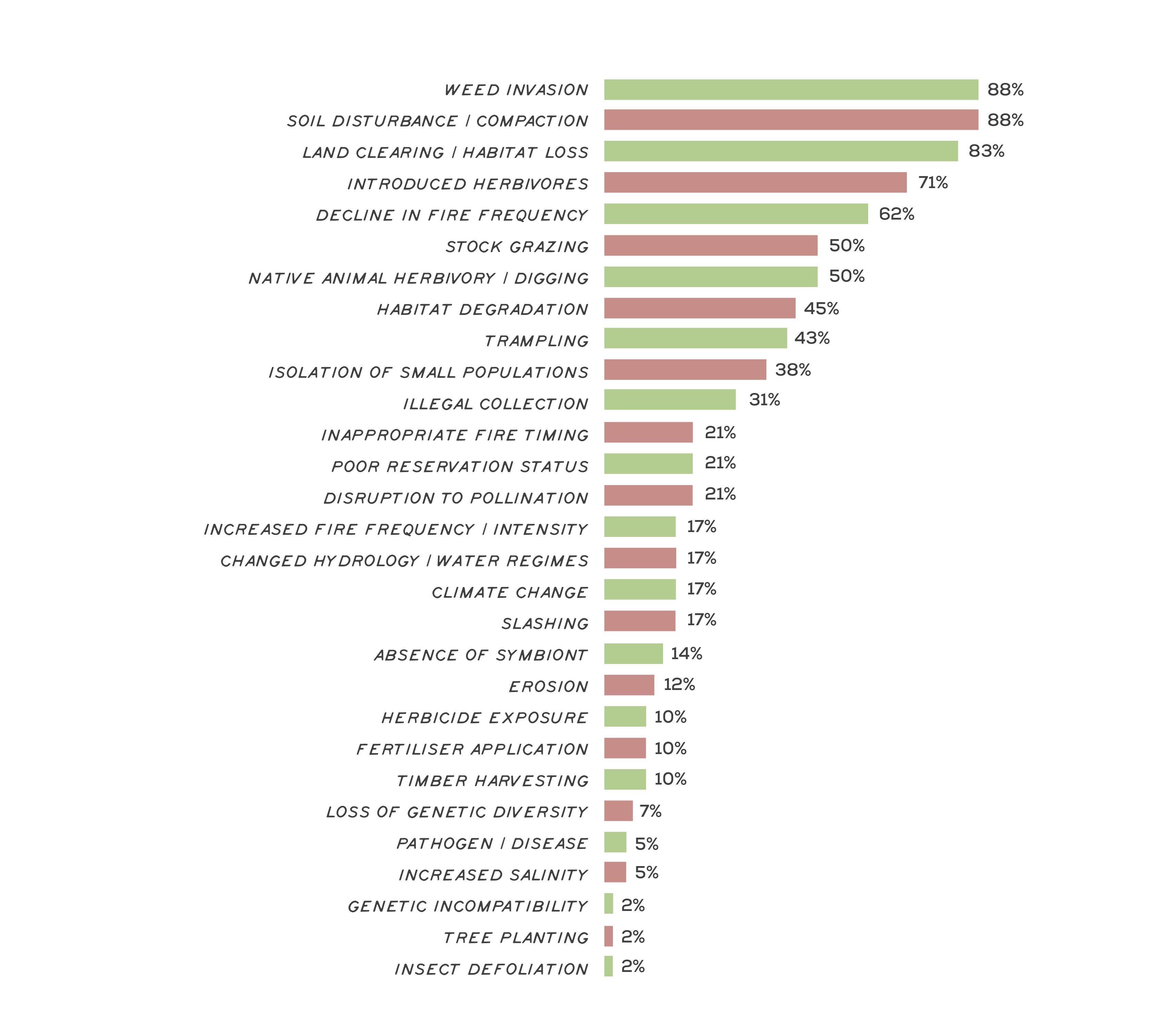

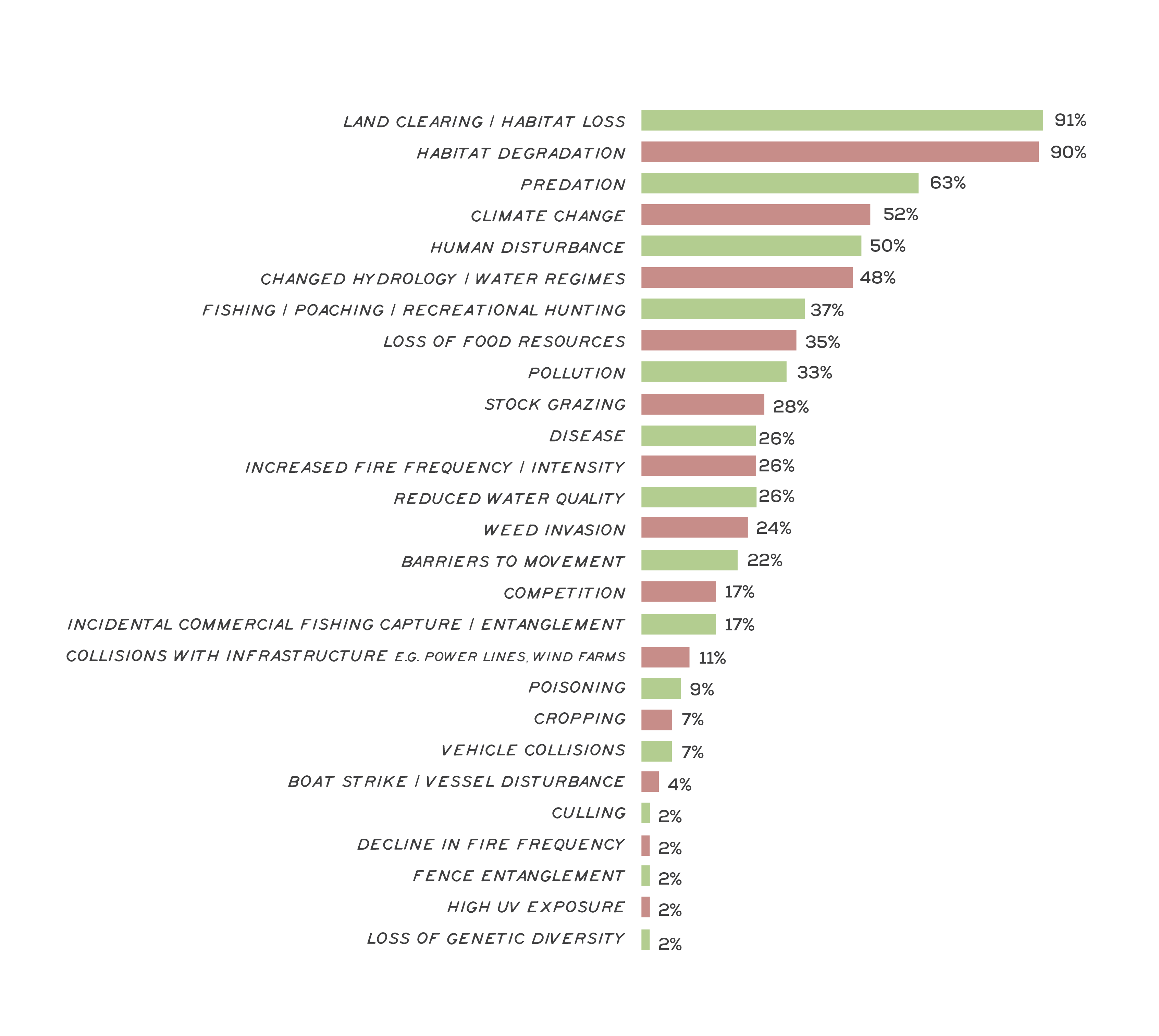

Land clearing has been identified as the most widespread threat to the region’s threatened species, with further habitat losses identified as a cause of decline in 88% of species Recovery Plans and Action Statements (Figure 2 & 3). To a large extent, species decline in the Glenelg Hopkins region is a legacy of past land clearing, with only 19% of native vegetation cover from the time of European arrival remaining. This trend of habitat loss is continuing, with losses since 2010 highest in the same areas where historical land clearing has been concentrated (e.g. 47% further loss of native grassland since 2010)7.

The categories of threats identified above range from pervasive (like climate change) to unique (like absence of a specific symbiont). Broad threats, which apply at the landscape scale and impact many species, include things like weeds and pest animals, land clearing, grazing and inappropriate fire regimes.

Climate change is emerging as another major threat to the region’s listed species through increases in temperature, extreme weather events and declining rainfall. Large amounts of uncertainty remain over how species will respond to these conditions, and cascading effects are difficult to predict as the relationships species depend on are de-coupled and break down. Semi-aquatic and seasonally inundated plants are expected to be particularly vulnerable. Concern over changes to hydrology and water regimes has also been identified specifically for many threatened animals. This includes species reliant on rivers and streams, such as the Glenelg spiny crayfish and the variegated pygmy perch, as well as those reliant on seasonal wetlands such as the brolga and the Australasian bittern8.

The role of fire in the Glenelg Hopkins region is nuanced. For many animals an increase in fire frequency and intensity is considered a threat, while for many plants a decline in frequency is a threat. This complex relationship between species and fire depends on the ecosystem they occupy. For example, native grassland on roadsides across the VVP provide habitat for many threatened orchids and daisies, such as the clumping golden moths and the button wrinklewort9. These species are poor competitors relative to the native grasses they share habitat with. However, regular burning both pre- and post-European arrival across the region kept grass structure open, providing these species with access to sunlight and the space needed to persist. Regular burning of grassland also provides the ideal habitat structure for the striped legless lizard, one of the few threatened animals for which a decline in fire frequency is considered a threat10.

In the more forested parts of the region, such as the Glenelg Plain and Greater Grampians, fire is considered a threat to animals in the context of large-scale, intense bushfires. For example, large-scale bushfires in the Grampians over the past 15 years have had a lasting impact on resource availability for the heath mouse and southern brown bandicoot11. Bushfire is likely to become an increasingly prominent risk with climate change12. Relatively low-intensity fire can also be a threat in some instances. For example, hazard reduction burning on the Glenelg Plain can limit food production for the red-tailed black cockatoo for up to a decade when fire scorches the tree canopy13. Managing the complexity of preventing large-scale bushfires while not compromising habitat through hazard-reduction burns is likely to become increasingly challenging.

Aboriginal cultural burning practices is helping to reduce bushfire risk while also protecting critical food resources for the south-eastern red-tailed black cockatoo

Introduced predators are a major threat to many native species

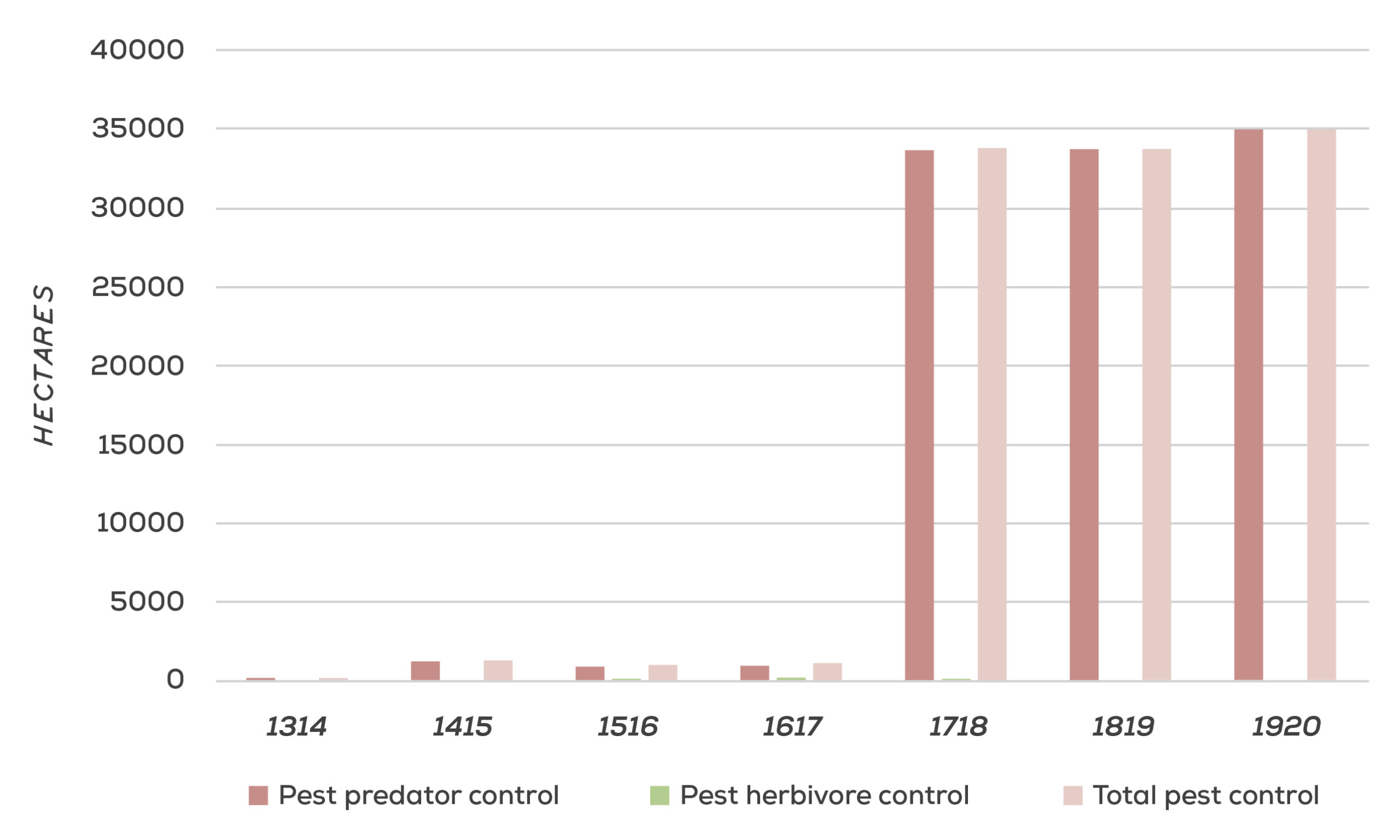

Species composition of the Glenelg Hopkins region has undergone a dramatic transformation since European arrival. To date, 41 pest animals and 653 introduced plants have been recorded in the region14. Many of these species are considered a threat through competition for resources, and direct predation and herbivory. The threat of predators is likely to be compounded by climate-driven events such as large-scale bushfires, with research demonstrating that predator efficiency increases in post-fire landscapes15. In the south-west of the region on the Glenelg Plain, there has been extensive work to protect vulnerable animals from predation through the Glenelg Ark project. This project has undertaken fox control over 90,000 ha of highly significant habitat. As a result, there has been a substantial decline in fox numbers, leading to an increase in population numbers of the threatened southern brown bandicoot and long-nosed potoroo16. See Figure 4 for the area of pest control works in the Glenelg Hopkins region.

Weed invasion and soil disturbance have been the most commonly recognised threats to the region’s threatened plants. These threats are likely to be connected, as soil disturbance is generally the primary driver of weed invasion into areas of native vegetation17. Herbivory is also a major threat, particularly from introduced herbivores such as rabbits and stock grazing, but also from some of the region’s native herbivores. This is likely to have occurred due to the transformation of the environment, with European arrival affecting some native species more rapidly than others, creating an imbalance, with some native plants now vulnerable to the same herbivores they co-evolved with.

Outcomes and priority management directions

Outcomes and priority management directions have been developed to show what success looks like for integrated catchment management (ICM) across the Glenelg Hopkins region. Below is the 20 year (long-term) outcome for threatened native species. Within these are the proposed six-year outcomes and priority management directions to be achieved within the life of this strategy. The priority management directions are identified across the adaptation pathway stages of resilience, transition and transformation (see RCS approach for more information). Lead and key partners involved in delivery are also outlined.

By 2042, the health of key populations of threatened species and communities is maintained or improved

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Owner communities have the capacity, knowledge and authority to look after their understanding of threatened native species, including culturally significant species, and groundwater dependant species and communities. | Traditional Owner are partnering with agencies to manage threatened species. Traditional Owner groups are supported to implement traditional land management techniques. Traditional Owner groups are supported to increase knowledge of cultural landscapes and traditional practices, and share knowledge across their communities. | Agencies and authorities incorporate cultural knowledge and practices into management planning and practice, where appropriate. Cultural plant species are used in revegetation projects across the region. Knowledge around cultural plant species is shared and communicated with broader community where appropriate. | Traditional land management practices are reinstated for cultural landscapes and culturally significant species. Reintroductions of threatened and culturally significant species are trialed. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Local Government, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| 100,000 ha of priority locations are under sustained pest predator control.* | Control pest predators across 100,000 ha of priority locations through appropriate management practices (e.g. shooting and poison baiting of foxes, and feral cats). | Establish pest predators proof enclosures to provide species refuge. Support new technologies and innovation in monitoring and control of predators e.g. grooming traps for cats, alternative bait types and dispersal methods. | Consider innovative approaches to restoring predator/prey dynamics at controlled sites (e.g. reintroduction of higher order natural predators). | DELWP | Traditional Owner Organisations, Local Government, Parks Victoria, Trust for Nature, BirdLife Australia, Nature Glenelg Trust, Landcare and community based NRM groups |

| The trajectory of priority threatened species and ecological communities is stabilised or improved. | Threatened species or communities likely to require specific management are identified and prioritised for action, in line with Specific Needs benefit-cost analyses and/or relevant recovery plans/conservation advice. Partner with landholders to improve the management of threatened species and ecological communities on private land. | Develop options for critically endangered and endangered species to be conserved ex situ or re-established in the wild should they need it. Ensure all data collected on threatened species distributions and population sizes is submitted into the Victorian Biodiversity Atlas (VBA) to improve decision making. | Establish recovery teams and develop recovery plans for priority threatened endemic species across the region. Monitor all programs targeting the recovery of threatened species to assess effectiveness and identify trigger points for adaptive management, the trajectory of threatened species and effect of management interventions. Understand the genetic health of populations and implement genetic rescue where feasible and necessary. | DELWP, Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Traditional Owner Organisations, Local Government, Parks Victoria, Trust for Nature, BirdLife Australia, Nature Glenelg Trust, Landcare and community based NRM groups, Zoos Victoria, Wannon Water, CFA |

| Climate refuges for threatened species and ecological communities vulnerable to climate change are established and protected. | Identify species and communities for which it is feasible/where there is a need to provide climate refuge. Prioritise refuge sites based on long-term site security, habitat type and on-going management capability. Establish initial climate refuge projects for key flora species. | Support research into the response of species and communities to climate change. | Establish climate refugia for key fauna species. Plan for revegetation programs to include a focus on supporting the movement of species and ecological communities along climate gradients. | DELWP, Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Traditional Owner Organisations, Wannon Water, Local Government, Parks Victoria, Trust for Nature, BirdLife Australia, Nature Glenelg Trust, Landcare and community based NRM groups |

*Outcome is linked to the statewide Biodiversity 2037 target, ‘1,500,000 hectares in priority locations under sustained pest predator control’. In the Glenelg Hopkins region the 2037 target is, ‘125,000 hectares in priority locations under sustained pest predator control’.

Key strategies and plans that relate to the delivery of threatened native species outcomes include:

- Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037

- Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2019-2030

- Australian Government Threatened Species Strategy 2021-2031

- Australia’s Native Vegetation Framework

- Growing What is Good Country Plan, Voices of the Wotjobaluk Nations

- Meerreengeeye ngakeepoorryeeyt, Eastern Maar Country Plan

- Ngootyong Gunditj Ngootyong Mara South West Management Plan

- Paleert Tjaara Dja, Let’s make Country good together 2020-2030, Wadawurrung Country Plan

A range of science based decision support tools are available to support the identification of priorities and management approaches to deliver outcomes for regional species and ecological communities across the landscape.

- Biodiversity Response Planning

- Strategic Management Prospects,

- Threatened Species Framework,

- Specific Needs Analysis

- Biodiversity 2037 Knowledge Framework which helps to identify knowledge gaps.

Climate change adaptation and planning is a core principle underlying the biodiversity outcomes of the RCS and is reflected in the identification of management priorities ranging from resilience to transition to transformation priorities. The following strategic documents provide guidance on climate change adaptation planning for biodiversity in the region, more information on the Climate Change page.

- Glenelg Hopkins Climate Change Strategy

- Natural Environment Climate Change Adaptation Action Plan 2022-2026