Meerteeyt Nyamat

Eastern Maar Sea Country

“Maar citizens have always had a close connection with the sea and its resources, which were central to our culture, economy and survival. The ocean nourished our Ancestors and we still rely on it for our survival. Abundant middens along the coastline tell a rich story of our past. The coastline is home to sites that are important for our Dreaming – Three Sisters Rocks and Deen Maar (Lady Julia Percy Island) where our Ancestors leave the earth.

Our connection with our Sea Country extends well beyond the current shoreline to the edge of the continental shelf. While this area is under the sea today, we occupied it for thousands of years and rising sea levels have not washed away the history, physical evidence or our connection.”

The Glenelg Hopkins region is characterised by its dramatic coastline, with towering cliffs and extensive dune systems carved out by changing sea levels, volcanic activity, and wind and water erosion. The Gunditjmara and Eastern Maar peoples have a strong cultural association with the region’s marine and coastal environment. The many middens along the coast are evidence of the long history of Aboriginal people gathering food from the marine environment. At Moyjil (Point Richie) at the mouth of the Hopkins River human habitation has been dated to at least 40,000 years1. Between Tyrendarra East and Port Fairy the Land and Sea Country of the Gunditjmara and Eastern Maar peoples meet and are co-managed2. Deen Maar, an island between Portland and Port Fairy is of cultural and spiritual importance to Gunditjmara peoples, who associate the island with the spirits of the dead3. The Convincing Ground (east of Portland) is the site of the first documented Aboriginal massacre in Victoria around 1833.

Eighty per cent of Victorians rate the marine and coastal environment as the most important natural feature of Victoria4. It contributes significantly to the economic, cultural, environmental, and recreational life of local, regional, and state communities5. Environmentally, it is rich in biodiversity, with many unique species and is home to a variety of threatened species. The coastal zone also contains many sites of Aboriginal and European historical significance and regionally significant ports and industry6.

Moyjil – Point Richie, Warrnambool, Eastern Maar Country

Photo: Warrnambool City Council

Cape Bridgewater, Gunditjmara Country

Key features

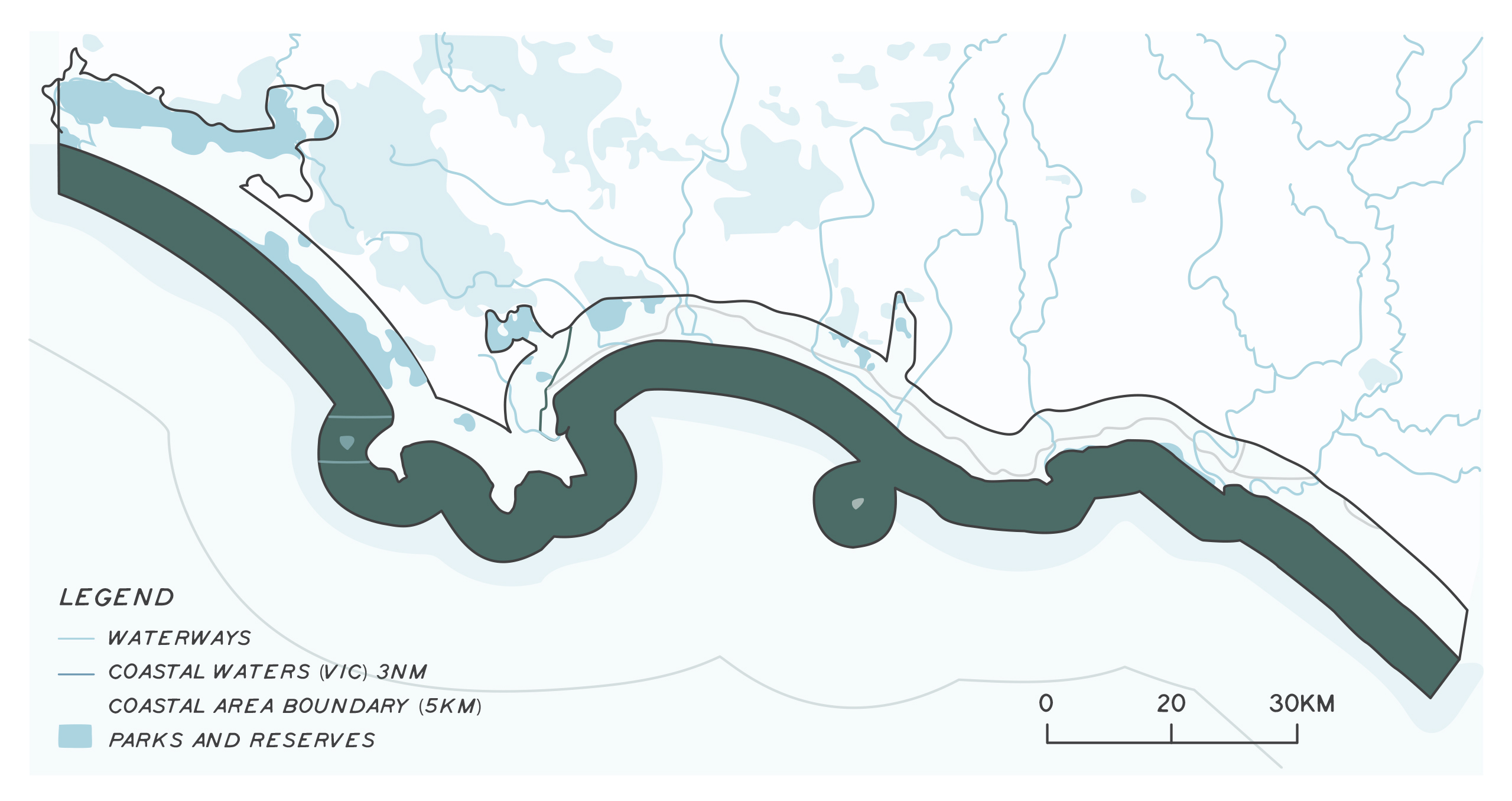

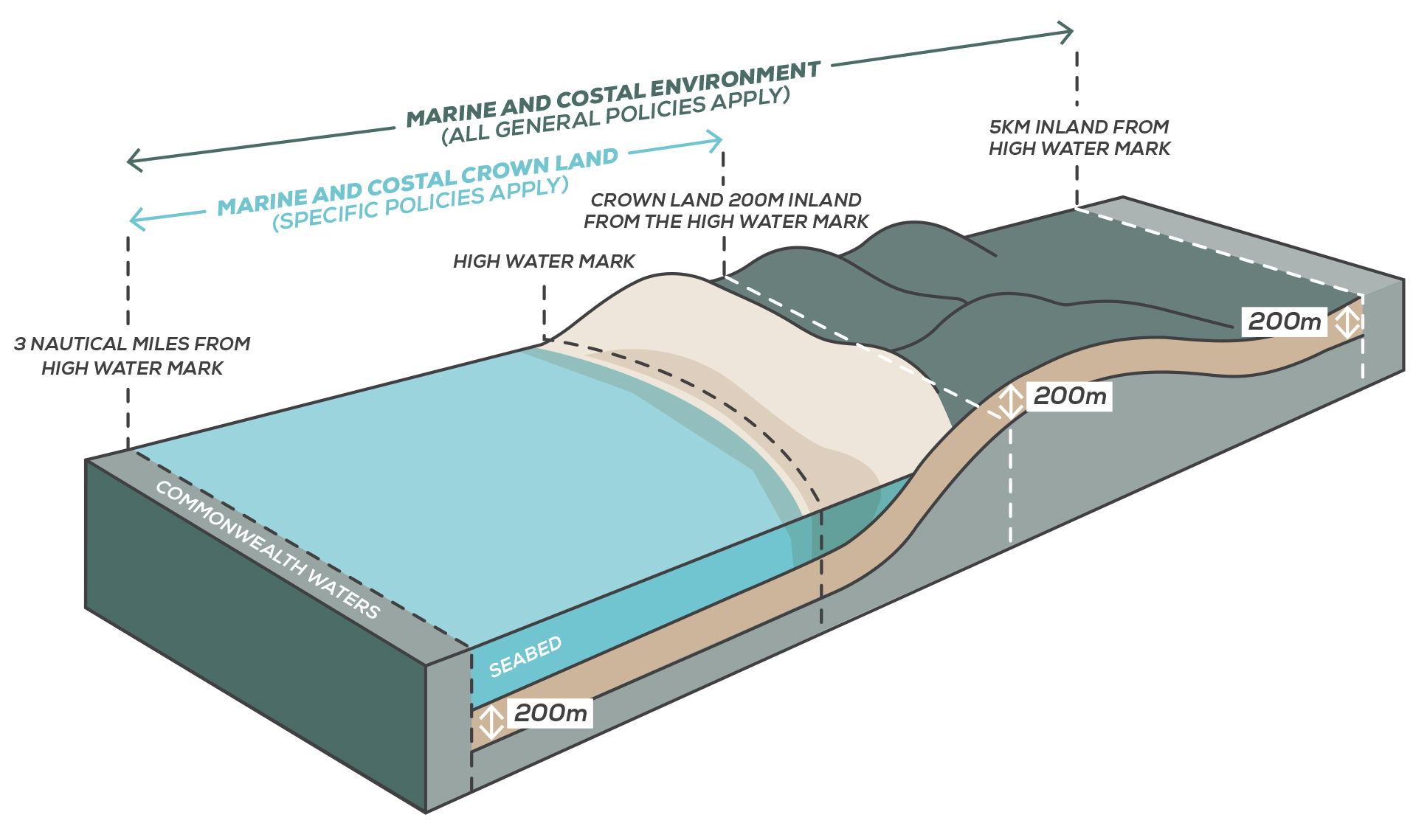

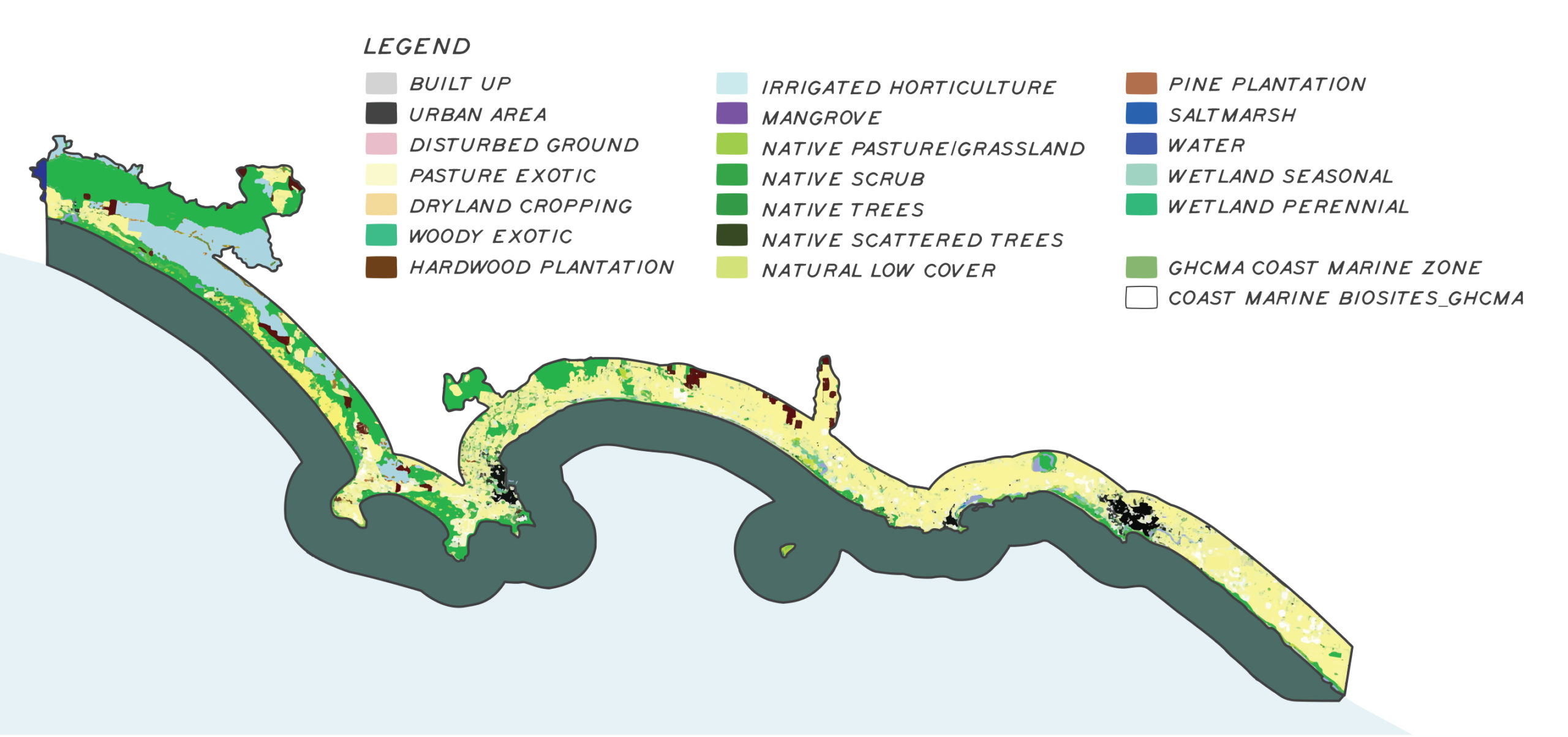

The marine and coastal environment of the Glenelg Hopkins region extends 220 km from South Australia east to just before the Bay of Islands (Figure 1). The marine environment extends out three nautical miles (5.6 km) to the state waters limit and covers about 142,360 ha (Figure 2)7. The coastal environment considers all land five kilometres inland from the high water mark, or further to encompass the long estuaries such as Glenelg, Surry and Lake Yambuk. All the marine and some of the coastal environment is in public ownership and some is protected as Parks and reserves managed by Parks Victoria, the new Great Ocean Road Authority and Traditional Owner groups8.

There are two marine protected areas in the region, Discovery Bay Marine National Park near Portland and the Merri Marine Sanctuary near the mouth of the Merri estuary, Warrnambool. Cape Bridgewater, Lawrence Rocks, Portland Bay, Deen Maar island and Logans Beach are special management areas. Coast areas managed for conservation include Lower Glenelg National Park, Discovery Bay Coastal Park, Mount Richmond State Park and The Bay of Islands Coastal Park. The Dean Maar Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) is near Yambuk. The Glenelg Estuary and parts of Discovery Bay were declared a Ramsar site in 2018.

The vegetation of the coast is shaped by the influence of the ocean, with long beaches and mobile dunes, coastal cliffs and sheltered volcanic bays, estuaries, wetlands, and lagoons. It is home to a wide variety of reptiles, birds of prey, waterbirds, woodland and ground-dwelling birds, and an array of mammal species. At the time of European settlement, it was dominated by forests, heathy and grassy woodlands and coastal shrubs and grasslands. Coastal vegetation has been extensively cleared as agricultural and urban areas have developed. The remaining habitats, particularly open coastal shrubs and shallow freshwater wetlands, are highly significant and vital for biodiversity conservation.

The region’s marine environment is characterised by its powerful waves; cold, nutrient-rich water; kelp-dominated rocky reefs; and a seafloor that drops away steeply offshore. In spring and summer, the Bonney Upwelling forms as south-easterly winds make the cold, nutrient-rich waters well up from deep water to the surface at the edge of the continental shelf. These nutrients support planktonic organisms and form the basis of rich food chain including krill, fishes, seabirds, penguins, fur seals and whales. It is one of only 12 known feeding areas in the world for blue whales9. Its reefs have rich assemblages of sessile filter feeders such as sponges and bryozoans10. The Bonney Upwelling is the basis for a rich and diverse fishery. Learn more about some of the region’s threatened marine and coastal species by clicking on the photos below.

The marine environment contributes significantly to the environmental, economic, and social values of the region11. It is one of the state’s most productive commercial fishing regions contributing $41.7 million of added value in 2016-2017 and 352 full-time jobs12. The three home ports – Portland, Port Fairy and Warrnambool – support a diversity of professional fisheries. This includes pipi, abalone, southern rock lobster, wrasse, southern squid, giant crab, southern and eastern scalefish and shark, and associated processing, wholesale, and retail sectors13.

Eels are commercially harvested from estuaries and rivers, with 54% of the catch coming from western Victorian coastal waters14. Estuaries and rivers with commercial licences are Eumerella River (including Lake Yambuk), Darlet Creek, Fitzroy River, Moyne River, Surry River, Shaw River, Moyne River (Belfast Lough) and the Merri River15. Abalone aquaculture is onshore at Narrawong and Port Fairy, and there is a reserve off Portland.

All forms of commercial and recreational fishing are prohibited in marine national parks and sanctuaries. Recreational fishing in the region’s marine and estuary waters is popular and worth more than $300 million to the economy. More information about recreational fishing licences, rules and catch limits can be found at the Victorian Fisheries Authority (VFA) website. To understand the recreational catch of rock lobster fishers need to tag their catch and provide carapace length to VFA16. Southern bluefin tuna, as a game fish, is a major drawcard for recreational fishing in the region with the majority (82%) of boats launching from Portland17. Recreational fishers on private or charter boats target juvenile southern bluefin tuna as they migrate between February and August with 82.6 tonnes caught in the 2018-2019 season18. Southern bluefin tuna is listed as conservation dependent under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and as threatened under the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988.

Assessment of current condition and trends

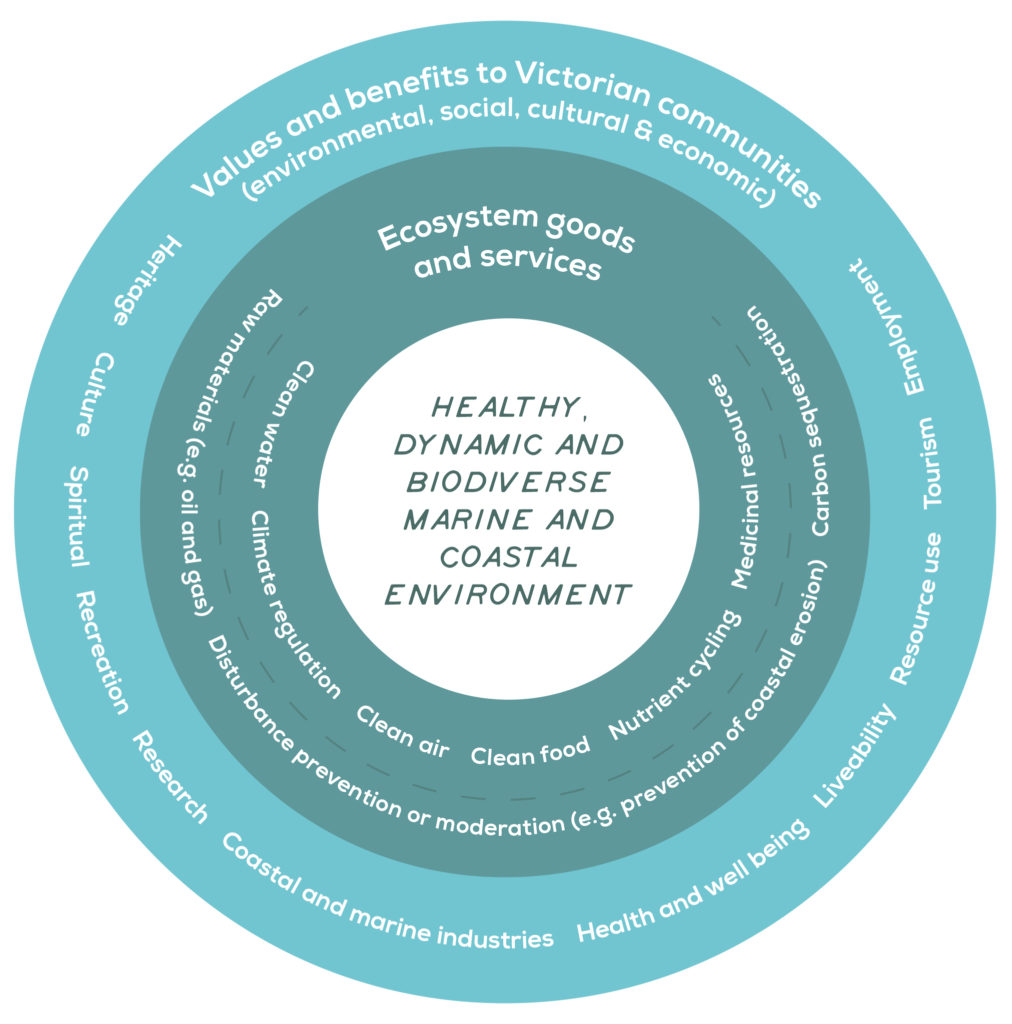

A healthy, dynamic, and biodiverse marine and coastal environment provides environmental, social, cultural, and economic values and benefit to Victorian communities (Figure 3). The ability to provide these diverse benefits is impaired when the condition of the environment decreases, so measuring condition and trends in condition are important in natural resource management.

The marine environment does not have any formal agreed measures for assessing condition, except for threatened species and conservation of marine ecosystems in protected areas21. Over recent decades, the fishing fleet and associated industries have contracted, mainly due to restructuring and the introduction of quotas, and the 2006 abalone virus22. The region’s main fish stocks have been assessed as being sustainably harvested23. In the past decade, with improved technology, nearly 60% of the region’s marine benthic area has been mapped, helping us understand shallow water coastal areas24.

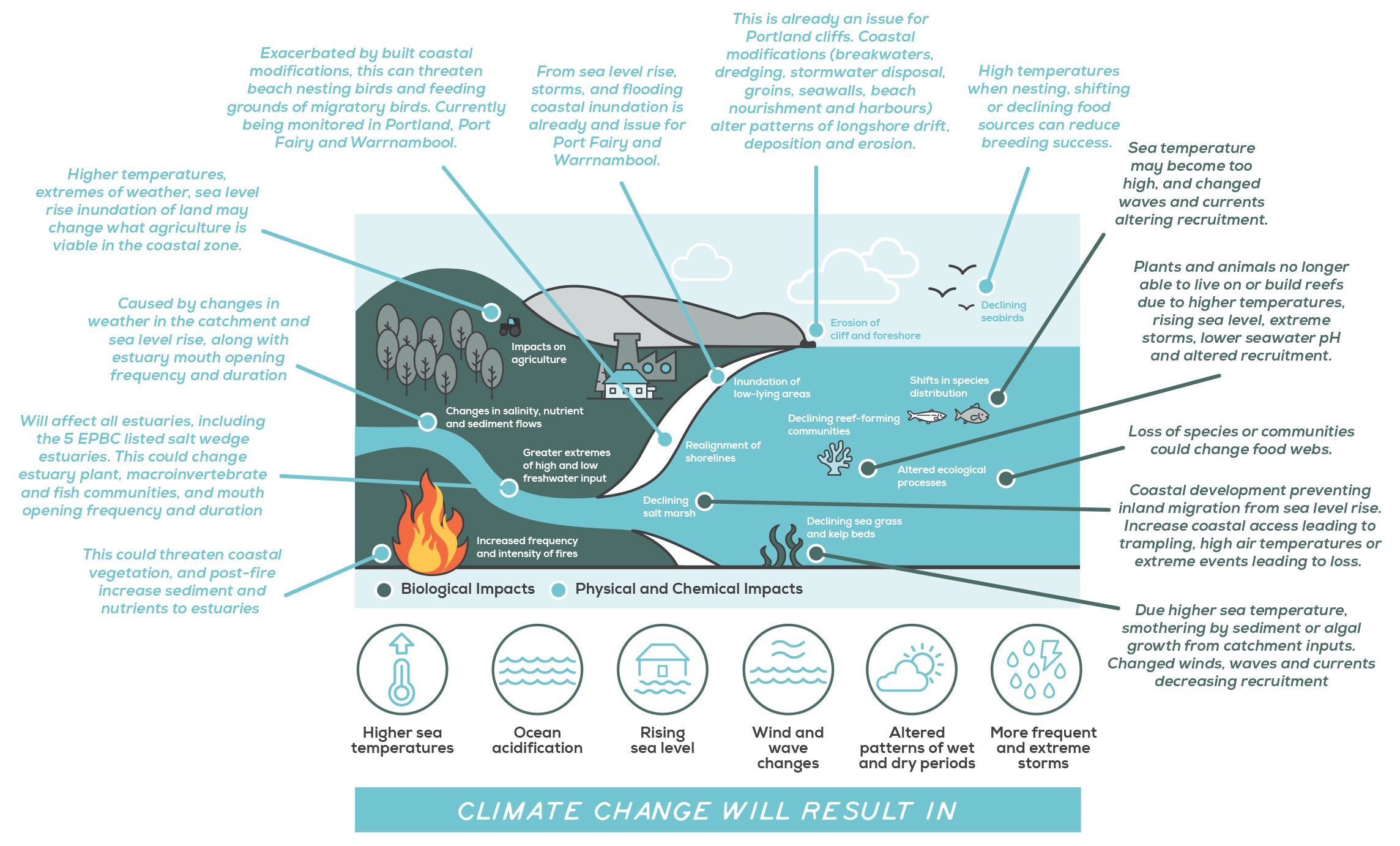

The coastal environment condition is assessed through estuarine and wetland health, extent of native vegetation, migratory shore birds and the presence of threatened species. The coastal environment is under extreme pressure and in marginal condition. Some specific asset areas may be in marginal to good condition, but they are generally in protected areas such as national or state parks. A key challenge for improving or maintaining the condition of the coastal zone is coastal development25. Where areas of the coastline are in high demand and subject to development pressures, coastal habitats tend to gradually fragment or are lost. Climate change will add further challenges and risk serious impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem health26.

Activities in the catchment directly and indirectly affect the marine and coastal environment through nutrient and sediment enrichment of waterways, chemical pollution and reduced freshwater flows. Improved management of activities in the catchment can help improve coastal and marine conditions.

Geoscience Australia has released a Digital Earth Australia Coastlines (DEA Coastlines) website, a continental dataset that includes annual shorelines and rates of coastal change along the entire Australian coastline from 1988 to the present. The site combines satellite data from Geoscience Australia’s Digital Earth Australia program with tidal modelling to map the typical location of the coastline at mean sea level for each year. This allows trends of coastal erosion and growth to be examined annually and for patterns of coastal change to be mapped and compared over time.

Estuaries

All estuaries in the region are in moderate to good condition (see estuaries theme for more information on condition and trends).

Coastal wetlands

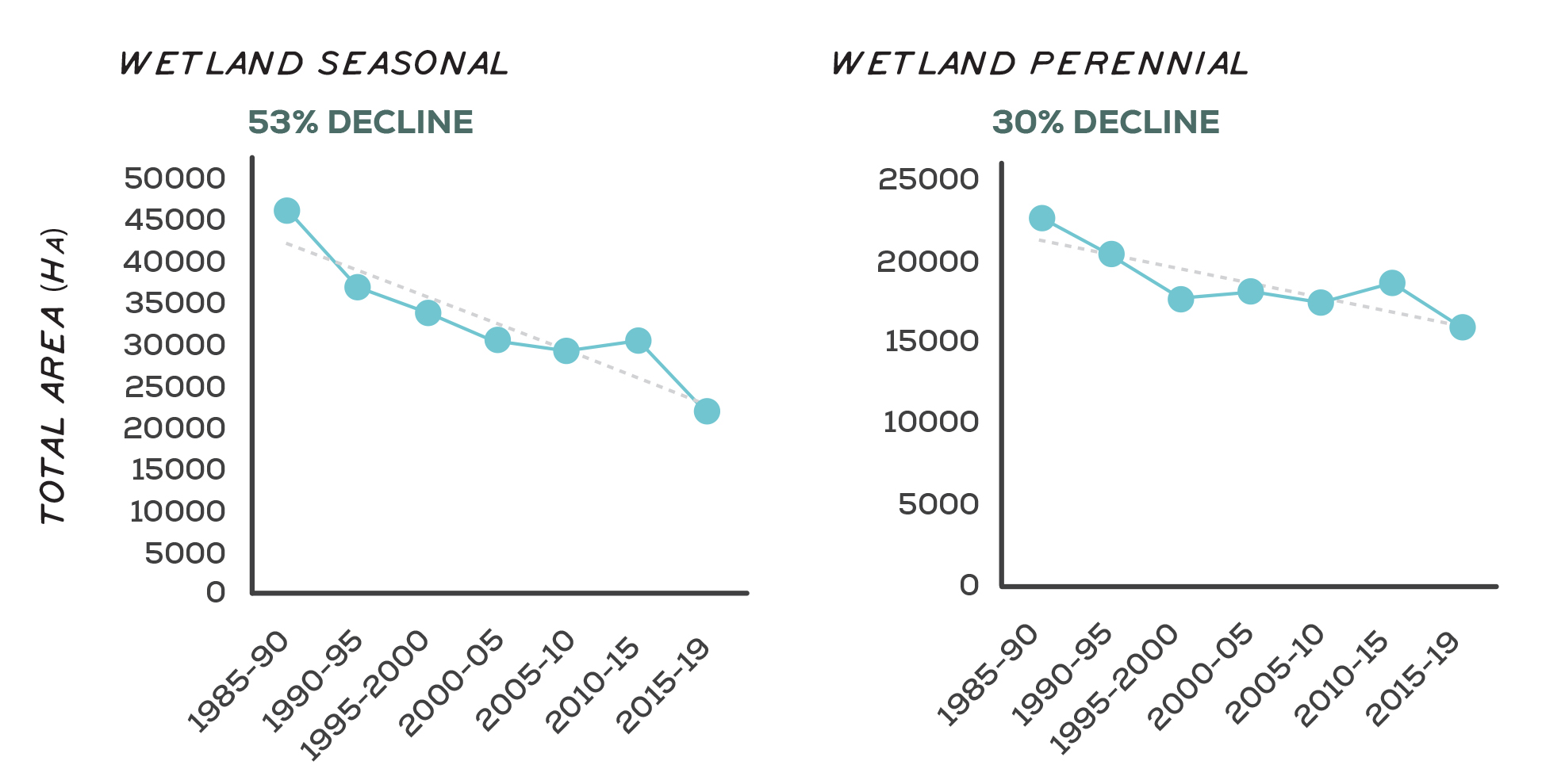

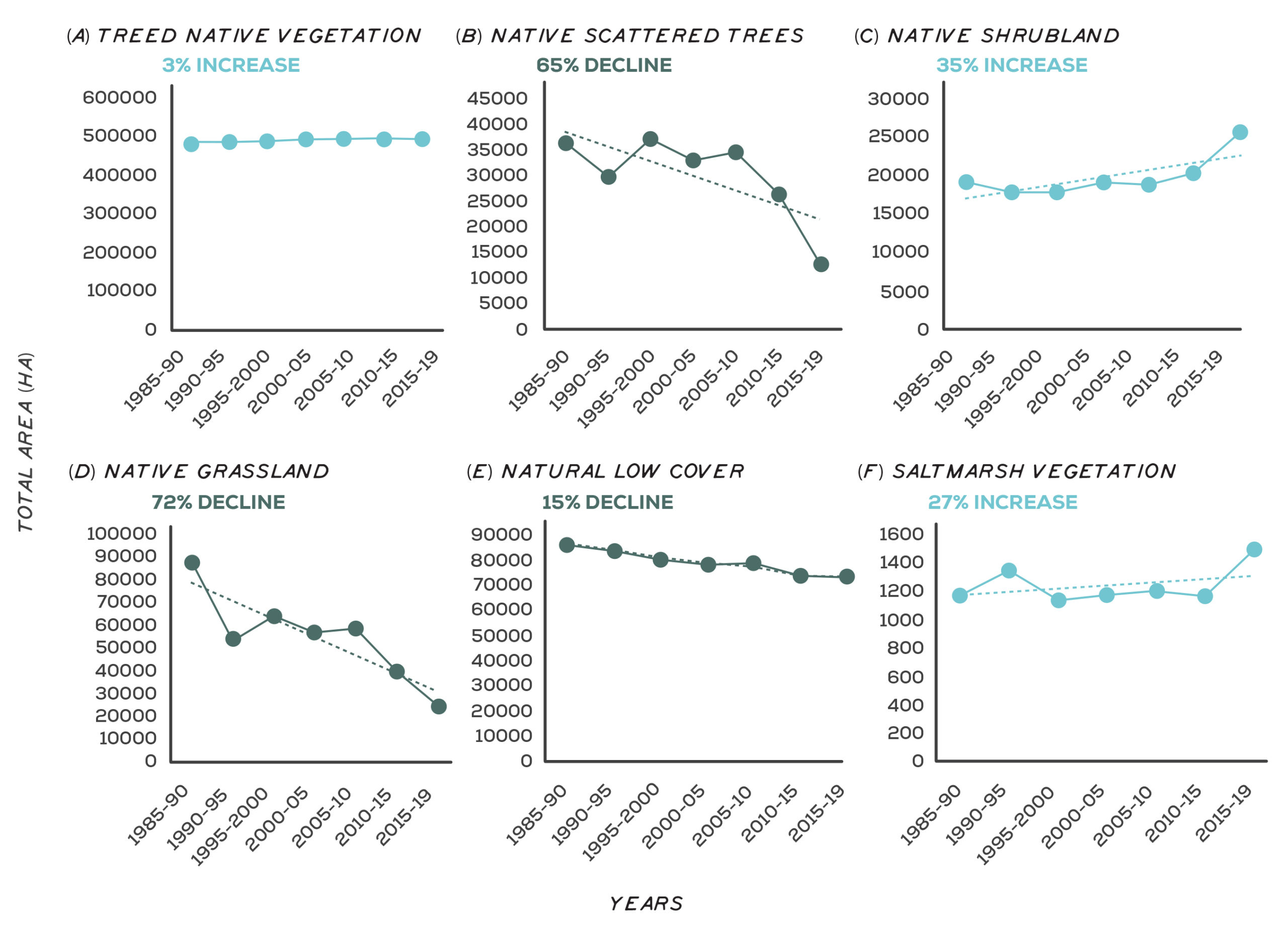

There are 259 coastal wetlands covering 4,396 ha, one quarter of which are in protected areas such as national or state parks and are primarily large wetlands. Seventy-five per cent of coastal wetlands are on private land, and are smaller, more fragmented, often drained and surrounded by cleared land used largely for stock grazing, including dairy. They can be sinks for agricultural drainage and run-off, decreasing water quality and changing inundation frequency. From 1985 to 2019 there has been a 53% decline of seasonal and 30% decline of perennial wetland vegetation in the coastal environment (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows the extent and spatial distribution of coastal vegetation within the coastal region.

Coastal vegetation

A wide range of habitats that support diverse and unique floristic species and communities are found along the coast. In the west, this includes relatively large pockets with good levels of connectivity with smaller, isolated patches in the east. Vegetation communities include coastal dune scrub, damp sands herb-rich woodland and associated wet and damp heathland complexes. A lot of coastal vegetation has been cleared for agriculture and further coastal development is a major fragmentation threat. Introduced animals, such as rabbits, contribute to the ongoing decline of indigenous species. Exotic and environmental weeds, particularly marram grass, coastal tea- tree, and New Zealand mirror bush, invade indigenous communities. From 1985 to 2019 there have been declines in the area of some native vegetation cover in the coastal environment (Figure 6). There has been a 65% decline for native scattered trees, 72% for native grassland and 15% for natural low cover vegetation. Conversely, there have been some increases in the area of some native vegetation cover in the coastal environment. Treed native vegetation cover area has increased by 3%, native shrubland by 35% and saltmarsh vegetation by 27%.

Coastal dune scrub, Tyrendarra, Gunditjmara Country

Damp sands herb-rich woodland

Major threats and drivers of change

Climate change and coastal development are major threats and drivers of change to the marine and coastal environment. They both exacerbate existing threats and bring new challenges. Ageing coastal protection structures (sea walls, groynes, breakwaters, piers and jetties) makes it difficult to protect coastal communities and support them to adapt27. The consequences of these threats and drivers are many and some are already measurable (see Figure 7).

Coastal areas are experiencing unprecedented increases in population and tourism activity28. This can lead to increased pressure for coastal access, recreational infrastructure, and seafood. Increased coastal development with increased coastal recreation can lead to:

- Coastal rivers, stormwater or wastewater outfalls conveying litter, elevating nutrients, and sediments. This causes reduced light levels, excess growth of algae, epiphytes, and phytoplankton, and decreased dissolved oxygen – which leads to a decline in seagrass cover, burial of rhodoliths, and decreased fish diversity/ abundance. Wastewater outfalls are sources of endocrine disruptors, heavy metals and plastics that can harm fish and mammals and contaminate seafood.

- Inappropriate artificial estuary opening produces silt plumes, fish kills and sedimentation.

- Ports, proximity to shipping lanes and recreational boats increase risks of oil or chemical spills. Boats can also be a source or vector for marine pest introduction or movement.

- Shore-based recreation (dogs, horses, vehicles) can disturb and harm beach-nesting birds, shore-feeding birds and seal colonies. Water-based recreation can disturb seal colonies and whales.

- Seagrass beds and subtidal reefs are damaged by anchors and scarred in shallow waters by propellers and vessel groundings.

- Coastal saltmarsh and intertidal reefs can be trampled and dunes eroded.

- Weeds displace native species in saltmarsh around estuary mouths and coastal wetlands.

- Introduced marine pests displace native species, The Port of Portland has at least 12 introduced pests.

- Introduced mammals prey on intertidal animals, and prey on or disturb roosting, feeding and nesting birds and eggs (a problem at Middle and Merri islands, and Point Danger).

- The abalone viral ganglioneuritis decimated abalone in the region in 2006 and could occur again.

- Foreshore light pollution in coastal towns disorientates birds like short-tailed shearwater fledglings.

- Fish stocks can change and be overfished due to impacts of climate change.

- Underwater seismic surveys for oil and gas disturb large (e.g. whales) and small (e.g. zooplankton, scallops, rock lobster) marine animals29,30.

Discovery Bay to Piccannie Ponds and Yambuk Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA) were both last assessed in 2008. The threat score for Discovery Bay to Piccannie Ponds KBA was medium, with threats to the site identified as invasive species and human disturbance through recreational activities. Yambuk KBA threat score was high due to abstraction of surface water, human disturbance through recreational activities and agricultural expansion. Port Fairy to Warrnambool KBA was assessed in 2016 with a very high threat score. The major threat to the site was human disturbance through recreational activities and agriculture with invasive species seen as a low threat.

Residential development has impacted several areas of coastal wetlands directly through drainage and conversion and higher-intensity recreational use. Large expanses of coastal vegetation have been cleared for agriculture and this fragmentation continues to be a major concern through future development of high-value coastal land.

Figure 7: Consequences of climate change on the marine and coastal environments

Storm waves inundate coastal road near Griffith Island Port Fairy

Photo: Moyne Shire Council

Rubbish collected from local beach

Seawall east beach Port Fairy

Photo: VCC

Outcomes and priority management directions

Outcomes and priority management directions have been developed to show what success looks like for integrated catchment management (ICM) across the Glenelg Hopkins region. Below are the 20 year (long-term) outcomes for marine and coast. Within these are the proposed six-year outcomes and priority management directions to be achieved within the life of this strategy. The priority management directions are identified across the adaptation pathway stages of resilience, transition and transformation (see RCS approach for more information). Lead and key partners involved in delivery are also outlined.

By 2042, Traditional Owner communities are decision makers and provide strategic leadership for Sea Country

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Owners rights, interests, obligations and access to coastal environments and sea Country, including water and cultural flows, are acknowledged and protected along the marine and coast environment. | Traditional Owner communities are supported to increase their understanding and awareness of their rights, interests, obligations and access to coastal environments and sea country; and Cultural Flows in coastal and marine environments. | Traditional Owners are supported to build knowledge across agencies, authorities and the general community of their rights, interests, obligations and access to coastal environments and sea Country. Understanding and awareness of Cultural Flows in coastal and marine environments is increased across agencies, authorities and the broader community. | Traditional Owners lead the integration of their rights, interests, obligations and access to coastal environments and sea Country into ICM. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | Parks Victoria, DELWP, Great Ocean Road Coast and Parks Authority, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| Traditional Owner communities have the capacity, knowledge and authority to look after Sea Country. | Traditional Owners partner in regional planning for marine and coastal environments. There is improved documentation and recognition of Traditional values and knowledge about Sea Country. Traditional Owner groups are supported to increase knowledge of cultural landscapes and traditional practises, and share knowledge across their communities. | Traditional Owners are supported to develop and implement Sea Country plans. Traditional Owners are supported to reinstate cultural practices and knowledge. There is an increased awareness of the region's cultural values. | Traditional Owners are decision makers in the management of sea country, including resource control. Traditional Owners rights to access and use the marine and coastal environment are recognised and supported. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | Parks Victoria, DELWP, Great Ocean Road Coast and Parks Authority, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| There is increased understanding and protection of at risk Aboriginal cultural values and heritage sites along the coastline. | Traditional Owners have a better understanding of the impacts and threats to Aboriginal cultural values and heritage found in Sea Country. | The regional community is educated on the impacts and threats to Aboriginal cultural values and heritage found in Sea Country. | Traditional Owners manage cultural heritage sites to reflect and protect their values in a culturally appropriate manner. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Parks Victoria. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Great Ocean Road Coast and Parks Authority, Local Government, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

By 2042, manage specific threats to coastal systems and improve condition where possible

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The amount of nutrients and pollutants directly discharged into the coast and marine environment is reduced. | Determine baseline and trend data by identifying priority managed outfalls and quantifying discharge. Manage catchment activities and education to reduce sedimentation and nutrients/pollutants flowing into estuaries. Issue works on waterway licences to ensure that works don't contribute to no increase in turbidity. Support the implementation of Water Sensitive Urban design (WSUD) across all new developments in the region. Manage new stormwater infrastructure is to minimise nutrient and pollutant discharges including litter. | Reduce the upstream application of nutrients (and other chemicals) resulting in runoff to estuaries/ocean. Improve treatment and screening for micro plastics. Manage existing stormwater infrastructure to minimise nutrient and pollutant discharges. Implement innovative Integrated Water Management projects across new developments that incorporate higher standards of Water Sensitive Urban Design to improve the quality of water to the environment. | Improve the monitoring and compliance of licences and other development permits to ensure the conditions are met. Advocate for more naturalised systems of water management in the coastal zone. | Wannon Water, Moyne Shire Council, Warrnambool City Council, Glenelg Shire Council, Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Parks Victoria, DELWP, Traditional Owner Organisations |

| There is improved understanding and management of threats to priority coast and marine species and ecological communities. | Educate the community about the values associated with estuaries/coastal ecosystems and relationship to management practices on land. Support changes to catchment management practices which impact coastal values. Manage direct threats to values, including pest plants and animals, development, disturbance and coastal erosion. Monitor changes in the extent of seagrass and giant kelp communities. Improve understanding of the impacts of recreational fishing on sensitive or poorly understood fisheries (e.g. citizen science project for recreational pipi harvesting). | Document groundwater discharge sites - marine and beach springs and food webs that rely on them. Consider the impacts of reduced groundwater discharge to coast and marine values in groundwater management plans. Minimise the spread of marine pest species. Identify sources of marine pests, including new species, and support increased monitoring, risk assessment and compliance to reduce introduction of marine pests. Research the impacts of discharges on the marine and coastal environment. | Support research to understand the impacts of noise and light pollution on marine species e.g. southern right whale. Research informs planning and management decisions to ensure conservation of impacted species. Investigate options to restore/re-establish lost seagrass beds | DELWP, Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Parks Victoria, Traditional Owner Organisations, Local Government, Victorian Fisheries Authority, research organisations, universities |

By 2042, improve the resilience and adaptive capacity of the marine and coastal environment and resources to the impacts of climate change and development

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Build climate resilience and adaptative capacity into planning approaches. | Contribute regional content to the development of the Marine and Coastal Strategy. Develop resources and processes to inform decision makers on the regional impacts of development decisions e.g. offshore exploration and development, fishing quotas. Develop or update Environmental Significance Overlays, planning scheme amendments, protected areas, development guidelines, visual landscape overlays to include coast and marine values. Complete mapping of known erosion zones, areas of increased inundation, dune movement and change over time. | Utilise the marine spatial planning framework to guide regional planning and development. Develop guidelines for consistent modelling of the interaction of catchment flooding and oceanic inundation in coastal waterways. Understand and map the inundation risk from natural estuary processes and climate change, and include in planning controls. | Identify high risk locations for coastal squeeze (due to coastal erosion, sea level rise, dune movement etc) and develop planned retreat options (for ecosystems and other values). Implement mechanisms to support movement of ecological communities/species (e.g. land acquisition, land use change, revegetation, erosion management, incentives to landholders). | Warrnambool City Council, Moyne Shire Council, Glenelg Shire Council, Glenelg Hopkins CMA | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Traditional Owner Organisations, CFA, Department of Transport, Nature Glenelg Trust |

| Community and stakeholders have improved understanding of coastal processes and adaptation options. | Develop a suite of programs for education about the coastal environment, processes and the impacts of climate change Strengthen relationships and partnerships at grass roots community level. Provide the community with opportunities to be involved with decisions about coast and marine management. | Develop a community hub for sharing information. Focus community education on values, expectations and understanding of change due to climate. | Climate change adaptation and disaster preparedness is driven through community action and the development of locally relevant plans. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | DELWP, Parks Victoria, Local Government, Traditional Owner Organisations, CFA, emergency and disaster response organisations, Nature Glenelg Trust, |

Key strategies and plans that relate to the delivery of marine and coast outcomes include:

- Marine and Coastal Policy 2020

- Marine and Coastal Strategy

- Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037

- Australian Government’s Threatened Species Strategy

- Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Landscapes Strategy

- Kooyang Sea Country Plan

- Glenelg Hopkins Climate Change Strategy

- Meerreengeeye ngakeepoorryeeyt, Eastern Maar Country Plan

- Ngootyong Gunditj Ngootyong Mara South West Management Plan

- Warrnambool Coastal Management Plan 2013

- Warrnambool Floodplain Management Plan 2018-2023

- Victorian Rock Lobster Fisheries Management Plan

- The Great South Coast Regional Strategic Plan