In the Glenelg Hopkins region, wetlands range from deep permanent lakes to shallow ephemeral marshes or swamps. They can be fresh or saline, large or small. The region has more than 7,600 mapped natural wetlands, covering 117,000 ha, or 4%, of the region’s area. This represents 22% of the state’s total number of wetlands.

Wetlands contribute significantly to the overall biodiversity of the region. They are an integral part of the region’s landscape and identity and underpin social, cultural and recreational values including boating, fishing, camping, swimming and bird watching.

Wetlands are also significant cultural sites across the region and continue to provide food, water and fibre for Traditional Owners. Aboriginal people have been intimately connected to the wetlands in this region for many thousands of years. These widespread and rich freshwater ecosystems supported permanent settlements across southwest Victoria and many wetlands retain their importance for cultural practices and ceremonies.

Brolgas are an iconic species found across the regions wetlands

Photo: Rod Bird, Brady Swamp

Wetland importance

Wetlands are some of the hardest working parts of the landscape. They help support the regional economy through tourism, agriculture and fishing activities. They absorb and filter floodwaters, replenish groundwater reserves and act as direct surface water supplies for stock1. Wetlands also store sedimentary organic carbon and account for a substantial portion of carbon stocks in the Glenelg Hopkins region2.

Several other wetlands are also listed as important under international agreements. The Glenelg Estuary and Discovery Bay Ramsar site and Lake Bookar (part of the Western District Lakes Ramsar site) are recognised under the Ramsar Convention as wetlands of international importance. The UNESCO World Heritage listed Budj Bim Cultural Landscape contains numerous wetlands that form the basis of complex eel farming aquaculture systems found across the site.

Wetlands provide vital habitat for migratory birds protected under international agreements and treaties: the Japan-Australia Migratory Bird Agreement (JAMBA), the China-Australia Migratory Bird Agreement (CAMBA), Republic of Korea-Australia Migratory Bird Agreement (ROKAMBA) and the Bonn Convention. More information on the significance of coastal habitats for migratory birds can be found in the marine and coast theme.

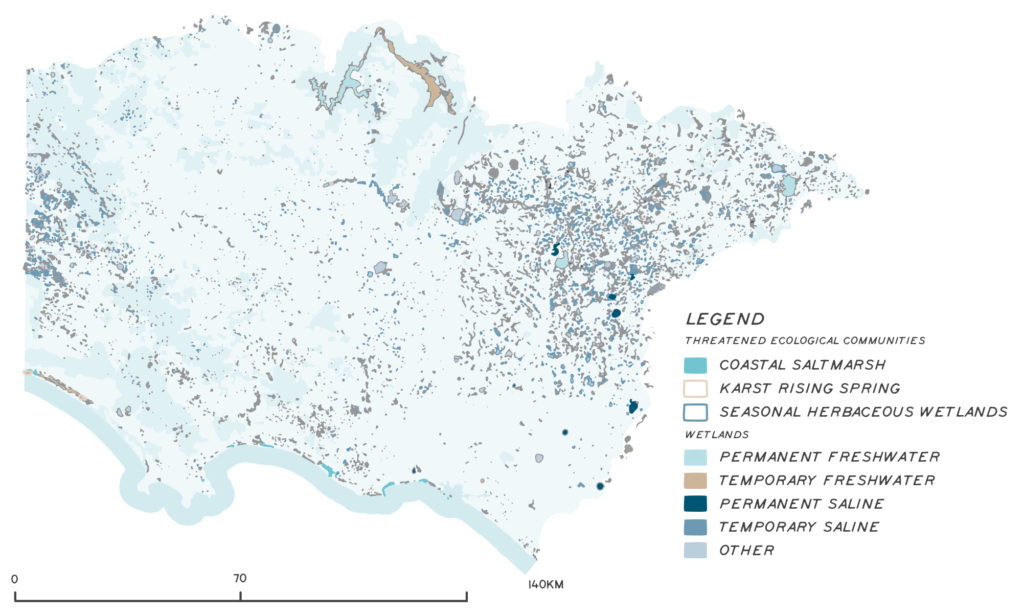

The Directory of Important Wetlands of Australia (DIWA) lists 16 of the region’s wetlands as nationally important. Three nationally listed threatened ecological communities occur in wetlands in the region (see Figure 1):

- Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains.

- Subtropical and Temperate Coastal Saltmarsh.

- Karst Springs and Associated Alkaline Fens of the Naracoorte Coastal Plain.

Wetlands support many nationally and state listed threatened species. More details are included on the rivers and threatened native species theme pages.

Wetlands occur right across the region, from inland to coastal locations. They are naturally found in high numbers in the flatter parts of the region, such as the Victorian Volcanic Plain and the border zone on the Glenelg Plain between South Australia and Victoria. While many large and high-profile wetlands are on public land, 80% of the region’s wetlands are on private land. The management of private land is very important to maintain the wetland and biodiversity values of the region.

Wetland diversity

Wetlands are classified based on the source of water, water quality (salinity), how often they get wet, how long they stay wet, and other landscape and vegetation characteristics. Regional wetland types can be loosely grouped as follows and there are saline and freshwater examples of each that support different vegetation communities. Freshwater wetlands account for 97% of wetlands in the region. Even though there are several large and well-known permanent lakes in the region, temporary swamps and marshes make up most of the wetlands in the region.

Lakes

Lakes are often large and relatively deep water bodies (>2 m deep) with typically less than 30% vegetation cover above the water surface. Examples may be fresh or saline, and include Lake Hamilton, Lake Bolac, the Bridgewater Lakes and Lake Bookar.

Swamps and marshes

Swamps and marshes are shallower than lakes, typically between 0.5 to 2 m deep, but depth can be variable across the wetland. Wetland vegetation can range from emergent plants like shrubs, sedges, grasses, reeds and rushes to submerged or floating herbaceous annuals. Examples include Walker Swamp, Church Swamp, Gooseneck Swamp and Long Swamp. The threatened Subtropical and Temperate Coastal Saltmarsh (Coastal Saltmarsh) ecological community is a type of saline estuarine marsh.

Meadows

Meadows are shallow wetlands, generally 10 to 50 cm deep, dominated by grasses (excluding Phragmites typically found in deeper marsh environments) and annuals. They are rarely permanent, often being filled on a seasonal basis. The threatened ecological community, Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands of the Temperate Lowland Plains, is a rare type of freshwater meadow.

Wetlands are classified based on the source of water, water quality (salinity), how often they get wet, how long they stay wet, and other landscape and vegetation characteristics. Regional wetland types can be loosely grouped as follows and there are saline and freshwater examples of each that support different vegetation communities. Freshwater wetlands account for 97% of wetlands in the region. Even though there are several large and well-known permanent lakes in the region, temporary swamps and marshes make up most of the wetlands in the region.

Lake Hamilton

Photo: Southern Grampians Shire

Long Swamp

Photo: Matt Herring

An example of a meadow wetland

Freshwater wetlands

The larger, deeper and more permanent freshwater lakes of the region provide important habitat for aquatic species that rely on the availability of permanent water, like fish and waterbirds. During drought periods or dry seasons, these wetlands provide important refuge habitat for a range of species. These wetlands are often well known and valued for the recreational activities they support including boating, water skiing and fishing.

The more numerous, but small and shallow seasonal wetlands scattered across the region are no less valuable and support a greater diversity of wetland species. These wetlands regularly dry out, for weeks or months, and they support highly adaptable species that not only tolerate a dry phase, but also often need it to complete their life cycles.

Many waterbirds favour the region’s swamps and marshes for breeding and feeding. One of the region’s most iconic species, the brolga, listed as threatened in Victoria, is a common user of temporary freshwater wetlands, building their nests from grassy material and feeding in the shallows. Wetlands are also important to both aquatic (platypus, water rats) and terrestrial mammals (swamp antechinus), which use wetland vegetation for feeding or habitat while bats feed on insects over water.

Wetlands of the region support 13 frog species, particularly in those wetlands where there are few fish, which predate on frog eggs and tadpoles. Wetlands are habitat for a rich diversity of invertebrates, which underpin food webs and perform other important functions, like breaking down organic matter.

Saline wetlands

Just over 3% of the region’s wetlands are saline wetlands. Saline wetlands generally form in coastal areas, where seawater enters wetlands via estuaries and prevailing winds transports salt which accumulates over time. There are also large inland saline lakes in the eastern part of the region, formed through evaporation of water (and subsequent deposition of salt from groundwater over extended time frames). Many saline wetlands in the region can become temporarily fresh when receiving freshwater inflow, requiring the species that inhabit them to be salt tolerant and adaptable. Lake Bookaar, which is part of the Western District’s Ramsar site, is a permanent saline lake.

Assessment of current condition and trends

Wetland condition and extent

Wetland condition is governed primarily by the availability and quality of water. The development of 80% of the region for agriculture, incorporating large scale drainage in many areas, has combined with reductions in rainfall to impact the condition and extent of wetlands.

It is estimated that 50% of the region’s wetland extent has been lost since European settlement3. The shallow marshes and swamps lend themselves to drainage and conversion to grazing or other agricultural development, which is reflected in figures that indicate that the region has lost 78% of its shallow freshwater meadows and 66% of deep freshwater meadows4. A recent spatial analysis of extent of cropping in a subset of the Southern Grampians area revealed that at least 55% of wetlands in the area assessed are cropped to some extent5.

The last widespread field assessment of wetland condition in Victoria was the statewide Index of Wetland Condition (IWC). The IWC assesses aspects of the wetland’s soils, water, plants and the wetland catchment. Two hundred and sixty-one sites in the Glenelg Hopkins region were assessed between 2009 and 2011. Results indicated that wetlands on public land were in generally better condition than those on private land (see table below). Eighty per cent of poor to very poor condition wetlands were temporary freshwater marsh or meadow type wetlands. The IWC provides a snapshot in time for a limited number of sites, less than 2% of the region’s wetlands, and was concentrated in specific areas. It cannot necessarily be taken as an indication of the current condition of the region’s wetlands and was not designed to measure change over time.

Trends in wetland extent and condition

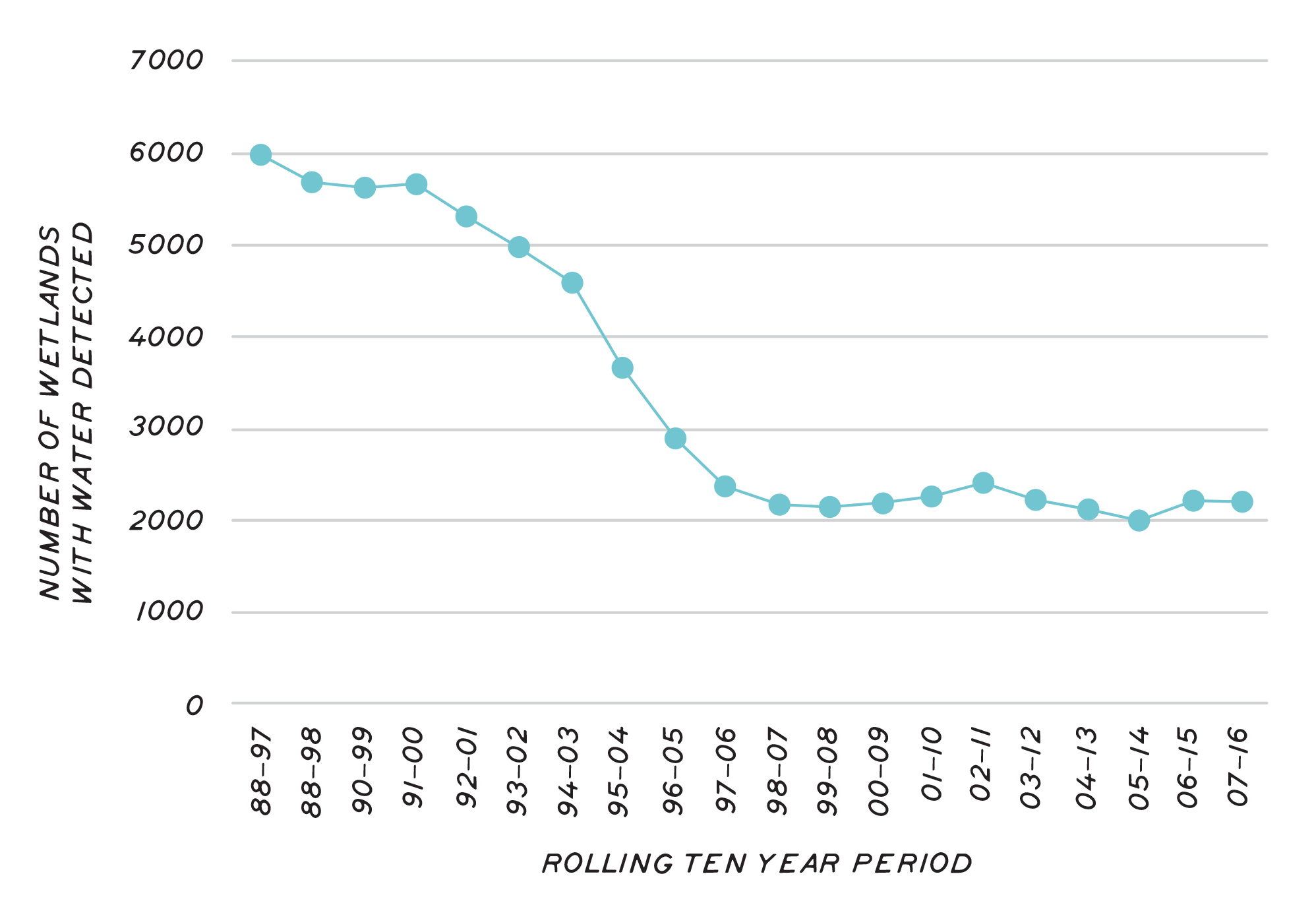

Current methods to assess wetland condition across the landscape rely on technology including satellite imagery. For example, several methods are now used across Australia to monitor the change in the availability of water in the landscape, detected in images collected from satellites. A significant change in the availability of water in the landscape occurred over the 2000s associated with the rainfall declines of the millennium drought. The Victorian Wetland Hydrology Monitoring project6 analysed satellite imagery for water signatures in the 7600 wetlands mapped in the region. The imagery dates back to 1988 so provides evidence of change over time.

Water can be detected by this method in around 6,000 of the 7,600 wetlands of the region in the 1988-1997 decade, this number dropping to around 2,000 in the 2007-2016 decade (Figure 3). The method was also used to assign a hydrological regime to each wetland and showed that the more shallow ephemeral types of wetlands showed the biggest declines in detectability, while the more permanent, semi-permanent and seasonally wet wetlands showed smaller declines.

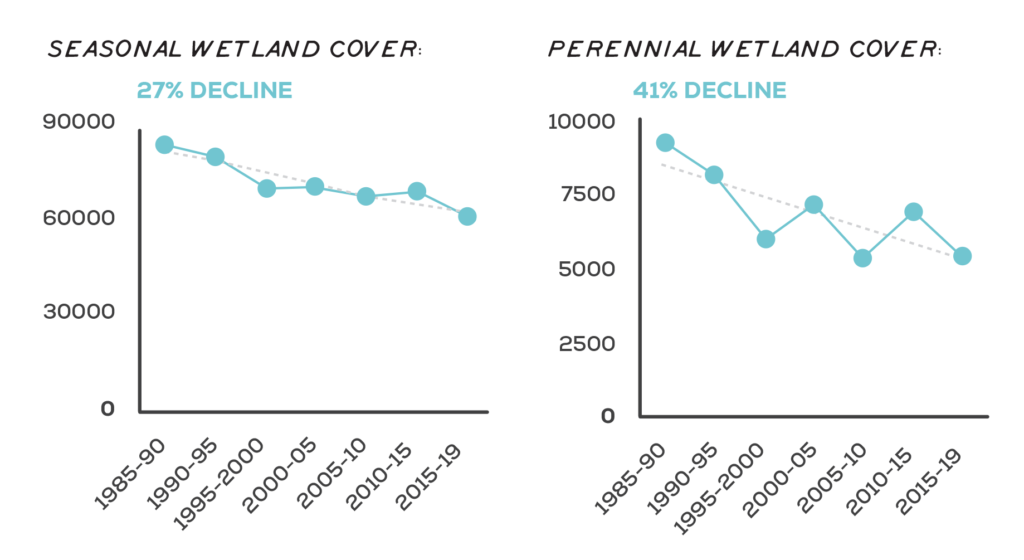

Consideration of change in wetland vegetation cover, over the period between 1985 and 2019, shows that the amount of native vegetation in wetlands has declined since 1985. Both perennial and seasonal native wetland vegetation cover decline significantly over that period (Figure 4).

Major threats and drivers of change

Threats to wetland function and values can operate at different scales. Individual wetlands are susceptible to changed water regimes, bush fires, altered physical form, reduced wetland area, poor water quality, reduced connectivity, exotic flora and fauna, degraded habitats and soil disturbance.

Landscape-scale threats operate at the regional, national or global scale and include climate change, reduced rainfall (hence runoff), increased evapotranspiration, altered groundwater availability and lack of connectivity and landscape permeability.

Land clearing

Land clearing is a major cause of biodiversity losses globally7 and threatens wetland biodiversity in the Glenelg Hopkins region.

There has been extensive land clearing in the region since European arrival, with 83% of native vegetation cover now cleared. Historical land clearing has not been evenly distributed across the region. For example, while the Greater Grampians has retained 86% native vegetation cover, the catchment’s largest bioregion, the Victorian Volcanic Plains (VVP), has retained just 6%. The areas of highest clearance rates coincide with the parts of the region supporting wetlands.

A fringing zone of native vegetation around a wetland helps filter out sediments and nutrients, provide habitat for wetland wildlife, and reduce water exposure to the sun and wind. If the fringing zone is cleared or degraded, these benefits are lost.

Wetland vegetation, like all vegetation in Victoria, is protected by state legislation from illegal clearance. Urban and industrial development and road construction are other forms of development that can also result in clearance of wetland vegetation.

Drainage and other physical works

Historical and current drainage of wetlands provides gains for agricultural productivity but is a significant threat to wetlands and the species that rely on them. Wetlands in south-west Victoria have been particularly affected. In the Glenelg Hopkins region, 75% of shallow freshwater wetlands have been lost due to drainage8. Wetlands are important systems for holding water in the landscape for longer. Drainage reduces the ability of wetlands to hold water and disrupts the complex ecological processes that take place in wetlands. It may result in a wetland drying out completely or faster, but the converse is also a risk. Water drained from the landscape must be diverted somewhere and can impact on receiving environments, making them wetter for longer and depositing additional nutrients.

Excavation or land forming (such as the construction of a dam in the bed of the wetland) will change the wetland’s depth and may damage or remove the confining layer that holds water in the wetland. Ploughing, deep ripping, mounding and even cultivation to sow crops can also significantly disturb the bed of shallow wetlands.

Changed land use

Conversion from predominantly grazing to cropping, or from broadacre to irrigated cropping or even changing from one type of crop to another, can affect wetland condition. Land uses that require more chemical or nutrient application can impact the wetland water quality. Activities change surface water or groundwater availability, such as establishing plantation forestry around or through wetlands, can negatively impact wetlands. Land-use change is intensifying in the region and is likely to continue as the agricultural sector adapts to climate change.

Water ribbons – a common plant in still to slow-flowing fresh water permanent swamps, lagoons and streams

Photo: Nature Glenelg Trust

Wetlands, such as this one, can be protected through landholder stewardship programs across the region

Water quality

The State Environment Protection Policy (SEPP) (Waters) defines environmental quality indicators and sets water quality objectives in Victorian waterways (including wetlands). The objectives set levels for each water quality parameter to protect the beneficial uses of water. Beneficial uses can include purposes such as ecosystems, human consumption, agriculture, aquaculture, industry and commerce, recreation and Traditional Owner cultural values.

Water quality in wetlands is influenced by the source of water, for example nutrients, agricultural chemicals and sediments washing off the surrounding landscape or washing down a river. Wetlands that receive water off large developed catchments, floodplains and via flow from other wetlands may accumulate pollutants as inflows stop and water evaporates.

Algal blooms are commonly associated with poor water quality and impact the use, enjoyment and safety of some of the lakes in the region. They are caused by the excessive growth of a family of naturally occurring bacteria found in the region’s waterways. When conditions are suitable, they can proliferate and form dense blooms to a point where they discolour the water, form surface scums, produce unpleasant tastes and odours, affect fish, cause rapid changes in dissolved oxygen and release toxic substances. When blooms die, the decomposition of algae cells can deplete oxygen and kill fish9.

Salinity changes that are outside the normal range that aquatic species can tolerate threaten survival and breeding success. Excessive freshening of saline wetlands (e.g. due to diversion of freshwater) or increasing salinity in freshwater systems have an equally significant impact.

Water acidity can change rapidly when potential acid sulphate soils such as peat deposits dry, which can trigger a harmful chemical process.

Nutrient levels can become elevated when nutrient-rich runoff from agricultural and urban landscapes enter the wetland or when livestock access the wetland for grazing. Raised nutrient levels can cause excessive plant growth and algal blooms. Livestock, vehicles, carp and certain other activities can muddy the water, disturb wetland soils and affect plant growth. Overspray with pesticides, fertilisers, and other farm or forestry chemicals can also impact water quality in wetlands.

Climate change

All wetlands within the Glenelg Hopkins region face a range of threats exacerbated by climate change. Reductions in rainfall and changes in the timing of rainfall will impact wetlands and may affect species dependent on specific triggers for breeding and the resources necessary for them to complete their life cycles.

The two wetland types that will be most vulnerable to climate change are coastal wetlands (due to impacts of seawater inundation) and seasonal herbaceous wetlands (due to the impacts of changing water availability)10. A hotter and drier climate in the Glenelg Hopkins region will reduce many wetlands in size, convert some wetlands to dry land or shift them from one wetland type to another. Rising sea levels are also likely to lead to the loss and degradation of coastal wetlands and associated biodiversity11.

Grassy seasonal herbaceous wetland

Outcomes and priority management directions

Outcomes and priority management directions have been developed to show what success looks like for integrated catchment management (ICM) across the Glenelg Hopkins region. Below is the 20 year (long-term) outcome for wetlands. Within these are the proposed six-year outcomes and priority management directions to be achieved within the life of this strategy. The priority management directions are identified across the adaptation pathway stages of resilience, transition and transformation (see RCS approach for more information). Lead and key partners involved in delivery are also outlined.

By 2042, the function and resilience of wetlands are maintained or improved

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Owner communities have the capacity, knowledge and authority to look after wetlands and their restoration including cultural flows. | Traditional Owners undertake activities to care for wetlands in partnership with agencies and authorities, including cultural burning, weed and feral species control and revegetation. Tourism, festivals, community education increase community familiarity with Traditional Owner cultural values of wetlands. | Governments, agencies and authorities partner with Traditional Owner groups to educate and inform landholders about Traditional Owner cultural values of wetlands. Traditional Owners identify priority wetlands and work in partnerships to restore them. | Traditional Owner values and aspirations shape decisions on wetland management and restoration across all land tenures. Traditional Owners lead tourism and community education activities to educate broader communities about cultural values of wetlands. | Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation and Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Additional partners TBD. | DELWP, Local Government, Glenelg Hopkins CMA |

| The community has increased knowledge and capacity to collaborate on wetland management. | Conduct survey to establish baseline information on the community's current level of knowledge and capacity to collaborate on wetland management. Raise awareness of the community about wetland function, values, management, rights and responsibilities. Support landholders (technical advice, incentives) to undertake works and management practices to protect the values associated with wetlands. Provide technical advice, incentives and funding to support improved management or protection. Conduct wetland research and inventory assessments to improve data, mapping and documentation of values and function, to inform prioritisation, education programs and management advice. Ensure that works on waterways do not negatively impacted on the flow of water to wetlands. | Establish effective cross agency compliance actions. | Provide incentives to reduce management activities that result in increased emissions from wetland soils (e.g. drainage, clearance and exposure of sediments). | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Traditional Owner Organisations, Wannon Water, DELWP, Parks Victoria, Trust for Nature, BirdLife Australia, Nature Glenelg Trust, agricultural industry groups, Landcare Groups, local land managers |

| An increased number and diversity of wetlands are managed to restore function, mitigate threats and protect values. | Manage direct threats to wetlands (drainage, changed water availability, eutrophication, pest plants and animals, stock impacts, lack of connectivity) across public and private land. Undertake wetland inventory and surveys to improve understanding of wetland diversity, condition and values. Monitor land use change and its impact on wetlands. Implement programs that protect and manage the recovery of wetlands that support known threatened ecological communities or species. Manage threats to Ramsar listed wetlands. Develop interim water quality targets as part of the renewal of the Glenelg Hopkins Waterway Strategy. Establish covenants to protect wetland values in perpetuity. Provide landholders with access to grants to encourage conservation and improved management of wetland values. | Improve understanding of the role and potential of local wetlands in sequestering and storing carbon. Facilitate improved understanding and recognition of legal and protection of wetlands. Develop planning controls and updated Environmental Significance Overlays that protect wetlands and aquatic vegetation from inappropriate development and use. Complete a regional assessment to identify functionally resilient wetlands that act as refuge sites under dry conditions and prioritise for conservation/restoration. Consider the importance of landscape connectivity for wetland species in work prioritisation. | Establish and promote commercial drivers (e.g. carbon or biodiversity credits, environmental standards, MBIs, incentives) to encourage wetland conservation. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Traditional Owner Organisations, Wannon Water, DELWP, Parks Victoria, Local Government, Trust for Nature, BirdLife Australia, Nature Glenelg Trust, Landcare Groups, local land managers |

| The number and extent of wetlands with improved or restored hydrology has increased. | Support projects to reinstate the hydrology of wetlands throughout the landscape. Integrate wetland restoration and protection into urban environments, including via Water Sensitive Urban Design and Integrated Water Management projects. Improve drainage management plans to reduce impacts on the availability, quality and timing of water to wetlands. Improve the documentation of drains, their status and impacts and ensure that drainage scheme projects take account of the risks to wetland values. | Investigate incentive program for landholders to retain water on their properties (foregone production) which provide a benefit to the catchment, groundwater recharge, flood risk or environmental values. Investigate better compliance and enforcement opportunities to minimise drainage and degradation of wetlands. Develop and promote alternative farming practices that protect wetland function (e.g. alternative cropping and grazing regimes, new crop types). | Pursue compliance to have illegally damaged wetlands reinstated to the their original condition. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Traditional Owner Organisations, Wannon Water, DELWP, Parks Victoria, Local Government, Trust for Nature, BirdLife Australia, Nature Glenelg Trust, Landcare Groups, local land managers |

Key strategies and plans that relate to the delivery of wetland outcomes include:

- Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037

- Victorian Waterway Management Strategy

- Water for Victoria

- Glenelg Hopkins Regional Waterway Strategy 2014-2022

- Glenelg Hopkins Climate Change Strategy

- Our Catchments Our Communities

- Growing What is Good Country Plan, Voices of the Wotjobaluk Nations

- Meerreengeeye ngakeepoorryeeyt, Eastern Maar Country Plan

- Ngootyong Gunditj Ngootyong Mara South West Management Plan

- Paleert Tjaara Dja, Let’s make Country good together 2020-2030, Wadawurrung Country Plan

- Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2019-2030

- Australian Government Threatened Species Strategy 2021-2031

- Marine and Coastal Policy

- Victorian Fishing Authority Strategic Plan 2019 – 2024

- Freshwater Fisheries Management Plan

- Glenelg Hpokins Drought Refuge Strategy

- Great South Coast Integrated Water Management Strategic Directions Statements

- Ramsar Management Plans