Estuaries are where rivers meet the sea – a mixing place of seawater and the freshwater that flows from the catchment. They are highly valued by the local and broader community for their scenic beauty, recreational fishing, swimming, camping, bird watching and boating. Most estuaries have towns or other settlements along them and they are a significant drawcard for tourism. There has been investment in public infrastructure to support recreational use of estuaries, particularly those near population centres at Warrnambool, Port Fairy, Yambuk, Narrawong, Portland and Nelson.

All estuaries are culturally significant places. As highly productive parts of waterways, they provided a source of food to the Traditional Owners, marked boundaries and were important meeting places. They continue to be important to Aboriginal people of the region. The Fitzroy Estuary sits within the UNESCO-listed Budj Bim World Heritage Cultural Landscape.

Estuaries are dynamic, ever-changing environments that provide habitat for a wide diversity of species adapted to survival on the interface between the marine and freshwater environments. They provide essential breeding areas and drought refuge for many fish species, along with critical breeding and foraging areas for birds, invertebrates and aquatic mammals. They also support a diversity of aquatic plants, from sea grasses to salt marshes.

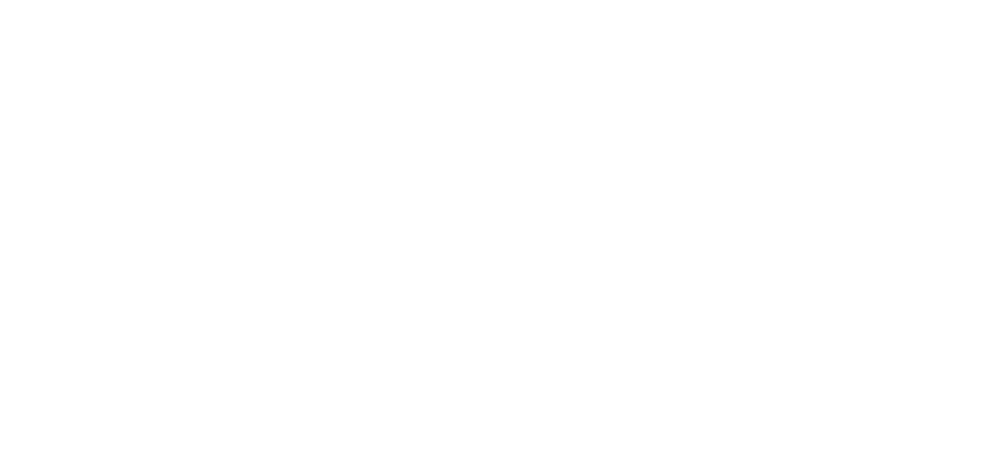

Glenelg River estuary

Estuaries in the Glenelg Hopkins region

The environmental significance of the catchment’s estuaries is recognised at a national and international level. The Glenelg River estuary is listed as a Ramsar site and a wetland of national significance in the Directory of Important Wetlands in Australia (DIWA). The Yambuk Lake complex and the Lower Merri River Wetlands (Kelly and Saltwater Swamps) are also listed as nationally important (DIWA) wetlands. Estuaries provide important habitat for migratory bird species that are protected under international agreements. The region’s estuaries also support two nationally listed ecological communities – Subtropical and Temperate Coastal Saltmarsh and the Assemblage of species associated with open-coast salt-wedge estuaries of western and central Victoria, as well as numerous threatened species.

The eight major estuaries in the Glenelg Hopkins region are the Glenelg River estuary, Fawthrop Lagoon, Surry River estuary, Fitzroy River estuary, Yambuk Lake, Moyne River estuary, Merri River estuary and the Hopkins River estuary. All are subtly different, influenced by local geomorphology, flow, degree of development along their rivers, and the condition of their catchment.

Most estuaries in the region are classified as intermittently closed, salt wedge estuaries. The Moyne Estuary and the smaller outlet associated with the Fawthrop Lagoon are now artificially kept open. The other estuaries close to the ocean following the natural formation of sand bars at their mouths. Closure is an important part of the natural cycle and function of estuaries and may happen several times in a year, generally coinciding with seasonal periods of low catchment rainfall and runoff. Estuaries that intermittently close will generally reopen following high rainfall events when there is enough water flowing down the river to flush the built-up sand from the estuary mouth.

The proximity of urban development and other fixed assets on the floodplains of rivers can be a challenge when river mouths are closed or when rainfall leads to short-term increases in river levels and subsequent inundation of the floodplain.

Assessment of current condition and trends

The condition of the region’s eight major estuaries is influenced by the landscape context they exist in, the interaction and availability of both fresh water and sea water and the degree to which they are influenced by local modifications and catchment inputs. Some of the region’s estuaries run though urbanised environments, some have extensive agricultural catchments, and others have small catchments with large amounts of native vegetation remaining. Freshwater inflows are driven by surface water via rivers and creeks, but groundwater is also known to contribute to the hydrological function of some estuaries. Some estuaries are subject to more human modification than others, with the Moyne estuary kept artificially open, and others are impacted by catchment and stormwater pollutants, drainage and the development of infrastructure. Estuary, river, and catchment management programs seek to maintain the function and condition of our estuaries, in as natural a state as possible, to support ecological diversity and the use and enjoyment of our unique coastal systems.

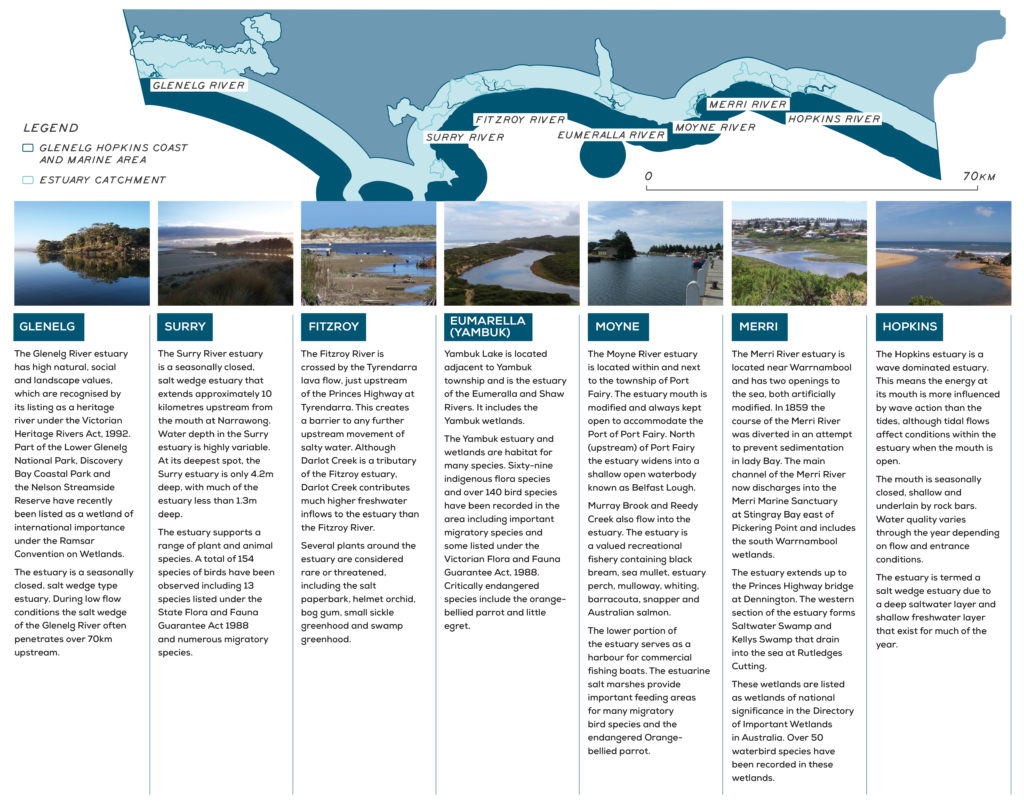

Estuary condition is classified via the Victorian Index of Estuary Condition (IEC). IEC provides a snapshot of estuary condition across the state at the time of monitoring. IEC results for all eight estuaries in the region (Figure 1) were published in 2021. The IEC focuses on five components of estuaries: fauna, flora, water quality, physical form (e.g. size and shape) and hydrology1.

Figure 1. Map of estuaries assessed by IEC in the Glenelg Hopkins Region.

Of the eight estuaries assessed by the IEC, three of these (37.5%) were in good condition, three (37.5%) were in moderate condition, and two (25%) were in poor condition (Figure 2). Catchments of estuaries in good condition, such as the Surrey River and Fitzroy River, tended to have higher cover of native vegetation than estuaries in poor condition (Moyne River and Merri River), which have ~90% of their catchment under exotic pasture (grassland).

Hydrology scores influence the overall rating a significant amount and reflect the degree of modification or management of the hydrology of the river. This includes the degree of diversion and capture of run-off throughout the catchment, artificial barriers to flow, changes to the marine exchange process and artificial management of the estuary mouth openings. Of note, the IEC assessed water quality across all estuaries as good or excellent, except the Merri River main channel, which was influenced by a large amount of chlorophyll in the water column – an indication of high levels of nutrients in the estuary.

Monitoring of water quality is an important component of the CMA’s estuary management and Estuary watch program. Consistent monitoring contributes to decision making about artificial river mouth openings, implementation of management actions and identification of emerging risks to estuary health. Data from regular water quality profiles and surface measurements from telemetry stations contribute to understanding physical and biological processes.

The values, condition and management of estuaries is impacted by the management of upstream rivers and their catchments. For information relating to flow, water quality and riparian condition of rivers, refer to the rivers page.

| Estuary | Physical form | Hydrology | Water quality | Flora | Fish | IEC score | Condition class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glenelg River | 10 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 30 | Moderate |

| Wattle Hill Creek (Fawthrop Lagoon) | 6 | 3 | 10 | 7 | NA | 28 | Moderate |

| Surrey River | 10 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 34 | Good |

| Fitzroy River | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 37 | Good |

| Eumeralla River | 9 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 34 | Good |

| Moyne River | 7 | 2 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 26 | Poor |

| Merri River | 7 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 26 | Poor |

| Hopkins River | 9 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 30 | Moderate |

Figure 2. IEC estuary results for the Glenelg Hopkins region

Major threats and drivers of change

Estuarine systems are complex and dynamic parts of waterways. As the interface between marine and freshwater systems, they are driven by ecological, physical and chemical processes that are easily disrupted. Major threats to estuaries are those that interrupt drivers of the system and compromise values.

Changes to natural estuary opening and closing processes

When estuaries naturally close, the resultant increase in water level has significant environmental benefits when adjoining wetlands and fringing vegetation are flooded. Conditions associated with river mouths being closed are important to the recruitment and survival of many species, including many valued fish species. However, there are also economic and social costs associated with excess water impacting on agricultural land, access and built infrastructure like jetties and roads.

Estuaries generally open naturally and artificial openings are only considered when conditions are safe, appropriate and effective, and the opening won’t compromise the ecological values of the estuary.

There are several potential negative consequences of artificially opening estuaries at inappropriate times, including fish deaths and the flushing of fish eggs and larvae out to sea. Glenelg Hopkins CMA uses the Estuary Entrance Management Support System (EEMSS) to evaluate the risks of artificially opening estuary mouths at different water levels and times of the year, and possible impacts on infrastructure and the environment.

Reduced water quality and availability

Water quality in estuaries is defined both by what flows down the river and from the marine environment. Excess nutrients and other pollutants from agricultural chemicals, urban runoff and litter all find their way into estuaries, which are at the end of extensive systems.

Water quality in estuaries is impacted by catchment condition. For example, the loss of riparian vegetation throughout the catchment means less woody debris washes down rivers. This debris is important throughout the river system to provide habitat for fish and other species. Catchment erosion also increases the turbidity of water and the amount of sand washing down rivers, eventually to estuaries, which can smother instream vegetation and fill deep pools.

Climate change

Estuaries and their associated wetland complexes are particularly susceptible to climate change impacts. A warming climate will result in reduced rainfall, increased evaporation and an increase in sea level. Increased ocean storm surge height can change the dynamics of estuaries dramatically and is likely to result in changes to natural opening regimes.

These changes will alter inundation and salinity regimes, and change water temperature, mixing processes and the water chemistry. In turn, this will impact on the ecology and biota of estuaries and will also affect infrastructure and the utilisation of estuaries and adjacent land.

Development and land use change

Predicted rapid population growth in coastal areas will increase development pressure, including along estuaries. Urban areas adjacent to estuaries result in increased recreational pressure, more pollution (from runoff, stormwater, litter), domestic cats and dogs’ impacts on wildlife, and loss of native vegetation to improve views and access. Poor planning can put infrastructure and the environment at risk by not allowing for natural movement in the estuary shoreline or water levels. Marine infrastructure, like rockwalls and marinas can also impact on estuaries, changing wave and flow dynamics and impacting the natural movement of sand.

Merri River estuary

Yambuck Lake estuary opening

Fitzroy River estuary

Outcomes and priority management directions

Outcomes and priority management directions have been developed to show what success looks like for integrated catchment management (ICM) across the Glenelg Hopkins region. Below is the 20 year (long-term) outcome for estuaries. Within these are the proposed six-year outcomes and priority management directions to be achieved within the life of this strategy. The priority management directions are identified across the adaptation pathway stages of resilience, transition and transformation (see RCS approach for more information). Lead and key partners involved in delivery are also outlined.

By 2042, manage specific threats to estuaries and improve condition where possible

| 6 year outcome, by 2027... | Resilience management priority | Transition management priority | Transformation management priority | Lead or coordinating responsibility | Delivery partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity between the freshwater and estuarine systems supports ecosystem health and maintains the diversity of species. | Support the protection and restoration of estuarine communities, including instream aquatic vegetation, coastal salt marsh and estuarine wetlands. Conduct a regional assessment of hydrological and fish movement barriers. Remove artificial barriers to increase resilience and provide retreat options for fish species. Monitor the movement and health of key habitats and fish populations along waterways. | Improve understanding of the value of connected floodplain wetlands to estuarine function, including fish breeding and diversity. Partner with local government to share information and protect remnant estuarine vegetation. Monitor estuarine seagrass extent and condition and utilise data to inform management and catchment planning. Develop planning controls and Environmental Significance Overlays that protect estuaries, listed ecological communities and remnant vegetation from inappropriate development and use. | Investigate options to restore/re-establish lost seagrass beds. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Parks Victoria, DELWP, Traditional Owner Organisations, Local Government, Wannon Water, Deakin University, Trust for Nature, BirdLife Australia, Landcare and community NRM groups, local land managers |

| The natural processes that support the values of Salt Wedge estuaries are maintained. | Continue estuary water quality monitoring program. Utilise the Estuary Entrance Management System to support natural estuary opening and closing regimes and processes. Implement community education and awareness-raising about natural estuarine processes and functions. Ensure land management practices within the catchment reduce sediment and nutrient inputs to estuaries. | Reintroduce structural fish habitat (e.g. fish hotels, woody debris). Encourage the installation of recreational infrastructure that can adapt to dynamic water levels (e.g. floating rather than fixed pontoons). Understand and map the inundation risk from current natural estuary processes and climate change, and include in planning controls. | Acquire land that is inundated by natural increases in water levels in estuaries including areas of predicted inundation risk under sea level rise scenarios. Manage land for improved conservation values (as riparian vegetation, wetland habitat etc). | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Parks Victoria, DELWP, Traditional Owner Organisations, Local Government, Wannon Water, Deakin University, Trust for Nature, BirdLife Australia, Nature Glenelg Trust, Landcare and community NRM groups, local land managers |

| Regional communities recognise and value estuaries. | Support community based programs and opportunities for volunteers and citizen science, e.g. Estuary Watch, Clean up Australia days. Pursue partnerships with recreational users to develop and implement options for managing estuaries and their values. Support community involvement in Coastcare and other environmental restoration programs. Improve access and visitor facilities that support experiences and recreational use of estuaries. Support community input into local plans and strategies, to protect and conserve estuaries in the face of increasing coastal development and climate change. | Promote the reduction of development pressures around estuaries. | Pathways to integrate management of upstream risks to estuary values developed with the catchemnt community. | Glenelg Hopkins CMA | Parks Victoria, DELWP, Traditional Owner Organisations, Local Government, Wannon Water, Deakin University, Trust for Nature, BirdLife Australia, Landcare and community NRM groups, local land managers |

Estuaries are waterways and subject to the same policy directions outlined in both the rivers and marine and coast themes. Key strategies and plans that relate to the delivery of estuary outcomes include:

- Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037

- Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2019-2030

- Victorian Waterway Management Strategy

- Glenelg Hopkins Regional Waterway Strategy

- State Environment Protection Policy

- Freshwater Fisheries Management Plan

- Fishing Authority Strategic Plan 2019 – 2024

- Victorian Floodplain Management Strategy

- Glenelg Hopkins Regional Floodplain Management Strategy

- Glenelg Hopkins Climate Change Strategy

- Integrated Water Management Framework for Victoria

- Central Highlands, Great Coast and Wimmera Integrated Water Management Strategic Directions

- Regional Riparian Action Plan

- Meerreengeeye ngakeepoorryeeyt, Eastern Maar Country Plan

- Ngootyong Gunditj Ngootyong Mara South West Management Plan

- Kooyang Sea Country Plan

- Marine and Coastal Policy and Strategy

- Warrnambool 2040

- Glenelg Shire 2040, Our Future Together

- Moyne 2040

References

- Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (2021). Assessment of Victoria’s estuaries using the Index of Estuary Condition: Results 2021. The State of Victoria, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, East Melbourne, Victoria.